“You didn’t mention camping on Mars.”

My wife had a point. The thin air, barren soil, intense UV rays, and jagged rock formations straight out of a NASA Mars photo made this place feel otherworldly. No wonder NASA’s Apollo program once considered training astronauts here. The sparse vegetation includes a thorny shrub as menacing as the scorpions that emerge after dark. Harsh and unforgiving, yet undeniably beautiful. We set up shade under our camper’s awning and waited for the magic hour—when the desert glows at dusk.

Tourists explore the Henbury meteor craters. (Photo: Genevieve Vallee/Alamy)

Driving along the Stuart Highway, it’s easy to overlook the Henbury Meteorites Conservation Reserve—a bumpy 12km detour off the main road, about 90 minutes south of Alice Springs. After seeing meteorite fragments at Alice Springs’ Museum of Central Australia, we were eager to visit the impact site. Of the six known meteor craters in the Northern Territory, Henbury and Tnorala (Gosse Bluff) are the most accessible. We visited both during Victoria’s fifth COVID lockdown in 2021.

Henbury’s craters were formed just 4,500 years ago when a nickel-iron meteorite, roughly the size of a garden shed, broke apart before slamming into the earth. The impact created over a dozen craters, and the event remains deeply significant to the Luritja people, whose oral histories describe it as a catastrophic moment.

Sign up for weekend reads, pop culture, and travel tips—delivered every Saturday.

Scientists estimate the meteorite struck at 40,000 km/h, with an explosion comparable to the Hiroshima bomb.

A meteorite fragment found at Henbury in 1931. (Photo: Matteo Chinellato/Alamy)

The 12 craters are best seen at sunrise or sunset when the low light reveals the smaller, eroded ones. Among the youngest impact sites on Earth, Henbury’s craters have been weathered by wind and occasional floods from the nearby Finke River. The largest crater spans 180m, while the smallest is about the size of a backyard spa. The explosion scattered pulverized rock in a distinctive rayed pattern—still visible around Crater No. 3, the only known example of this on Earth.

Fragments of the meteorite may still be found scattered around, though removing them without a permit is illegal. The Museum of Central Australia displays a 45kg chunk—part of the 680kg collected so far. We didn’t find any meteorite pieces, but we left with memories of a breathtaking sunrise and a night sky so clear the stars felt within reach.

The MacDonnell Ranges under a dazzling night sky. (Photo: burroblando/Getty Images)

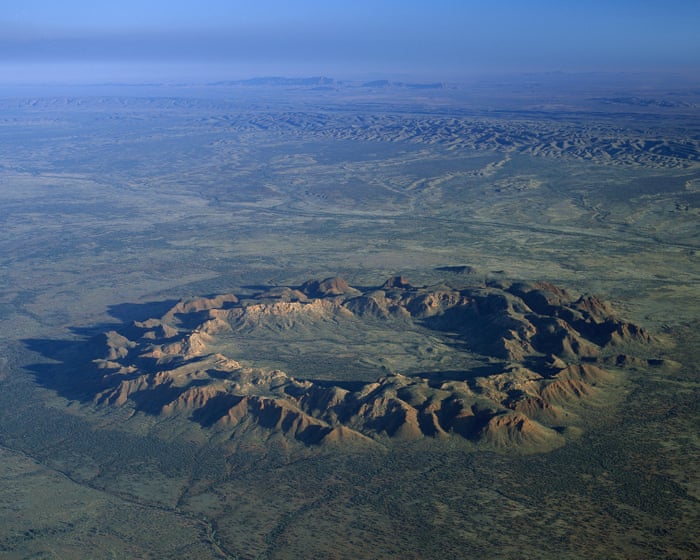

Two hours west of Alice Springs along Namatjira Drive, Tnorala (Gosse Bluff) rises abruptly from the flat plains. This striking formation was created 142 million years ago when an object up to 1km wide—likely a comet—slammed into Earth at 250,000 km/h. The impact released energy 20 times greater than all the world’s nuclear weapons combined.

No trace of the object remains—it probably vaporized on impact. Erosion has since reduced the crater from its original 22km diameter. From above, satellite images show an eerie resemblance to a staring eye beneath a sunburnt ridge.

The Larapinta Trail’s desert landscapes. (Photo: Andrew Herrick/The Guardian)

Fossils in the Museum of Central Australia reveal that this region was once cooler and wetter, teeming with dinosaurs. Any creatures near the Tnorala impact would have been vaporized instantly, while the shockwave and heat would have killed everything within 100km.

The sound of the explosion… (Note: The original text cuts off here.)The meteorite likely traveled around the world. The Tnorala impact was a precursor to the massive Chicxulub event in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, which wiped out the dinosaurs 77 million years later.

In Western Arrernte oral traditions, Tnorala is understood as a cosmic impact site. According to their stories, star women were dancing in the Milky Way when one placed her baby in a wooden cradle. The dancing shook the galaxy, causing the cradle to slip, and the baby fell to Earth as a blazing star, creating the crater’s bowl-like shape.

These days, “awesome” is an overused word—but it fits when driving into the 5km-wide Tnorala crater, surrounded by 180m-high cliffs formed in an instant by an Earth-shattering impact. The force was so immense that it lifted rock layers from 4km deep, flipping them upside down.

Tnorala is not just a site of ancient violence—it’s also a place of sorrow. Local signs describe it as a pre-colonial massacre site, making it doubly important that camping is forbidden.

This unwelcoming landscape is where a city-killer-sized object once fell from the sky. Thankfully, modern telescopes like Chile’s Vera C. Rubin Observatory can now detect such threats, and scientists have proven it’s possible to deflect them.

So forget Mars—cancel that ticket. Instead, visit awe-inspiring Central Australia, where mountains are upside down, stars seem within reach, and dawns are so quiet you can almost hear the sun sing.

### Need to know

– Museum of Central Australia: Hosting a Henbury Meteorite discovery day on 10 August for National Science Week.

– Henbury Meteorites Reserve: Accessible by 2WD (4WD recommended). Basic facilities include picnic shelters and a drop toilet. No water or firewood. Book campsites online. Nearest supplies are 85km south at Erldunda Roadhouse.

– Tnorala (Gosse Bluff): Reachable via a sandy track with picnic shelters and a drop toilet. Camping is prohibited as it’s a sacred site. Fuel and food available at Hermannsburg, 62km east. Beyond Tnorala, 4WD and a Mereenie Tour pass are required—roads may be impassable in wet weather.

(Fact-checking assistance provided by Associate Prof. Duane Hamacher.)