As mass deportations of migrants continue across America—along with disturbing reports of people being shackled or forced to kneel and eat “like dogs”—Nora Guthrie expresses disappointment that more musicians haven’t spoken out.

“I’ve been protesting every weekend,” says the 75-year-old daughter of folk legend Woody Guthrie and founder of the Woody Guthrie Archive. “And I keep wondering, ‘Where are the songs for us to sing about this?’”

Searching for a song that resonates with today’s struggles, she turned to Deportee, a track her father wrote in 1948 after a plane crash in California killed four Americans and 28 Mexican migrant workers being deported. “Days later, only the Americans were named—the rest were just called ‘deportees,’” explains Nora’s daughter, Anna Canoni, who recently took over as president of Woody Guthrie Publications. “Woody read about it in the New York Times and wrote the lyrics that same day.”

Originally a poem, the song (also known as Plane Wreck at Los Gatos) was later popularized by folk singers like Pete Seeger and covered by artists such as Bruce Springsteen and Joni Mitchell. Now, thanks to advances in AI audio restoration, Guthrie’s long-lost home recording of the song has been recovered—and its message about the dehumanization of migrant workers remains chillingly relevant.

“They fall like dry leaves to rot on my topsoil,” Guthrie sings, “and be called by no name except ‘deportees.’” Singer Billy Bragg notes, “With ICE rounding people up in fields today, the song couldn’t be more timely.”

Deportee appears on Woody at Home, Vol. 1 & 2, a new collection of 22 recordings—including 13 previously unreleased songs—made in 1951 and 1952, just before Guthrie was hospitalized for Huntington’s disease, which eventually took his life in 1967 at age 55.

“By then, he’d been blacklisted [during the McCarthy era] and couldn’t perform or get on the radio,” Nora explains. “Huntington’s was affecting his body and mind. These recordings were his last effort to get his songs out before it was too late.”

Guthrie’s empathy for migrant workers and his fight for social justice came from personal experience. Born into a middle-class Oklahoma family, he lost his home at 14 and lived through the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression, World War II, and the rise of fascism.

“He migrated from Oklahoma to California,” says Bragg. “He knew what it meant to lose everything, to be forced onto the road. The ‘Okies’ were treated no better than those Mexican workers—hated just the same.”

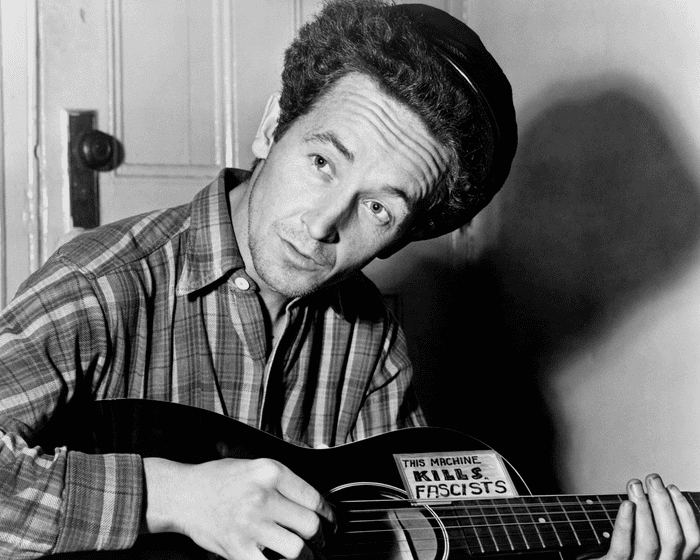

Guthrie famously inscribed his guitar with the slogan “This machine kills fascists” and filled his 1940 album Dust Bowl Ballads with what Anna calls “hard-hitting songs for hard-hit people.” His most famous anthem, This Land Is Your Land—which opens Woody at Home with additional verses—was written after a cross-country trip, as the lyrics say, “from California to the New York island.”

“Woody wrote it because he was sick of hearing God Bless America on every jukebox,” Bragg says. “It drove him crazy. I’ve seen the original manuscript—his first title, God Blessed America for You and Me, was crossed out at the top.”Woody Guthrie’s prolific songwriting—with 3,000 songs written between the 1930s and 1950s, including over 700 recordings—solidifies his status as both an alternative songwriter and a quintessential punk rocker. The “Woody at Home” recordings were captured in his family’s rented Brooklyn apartment using a basic machine provided by his publisher, intended to sell songs to other artists. Despite declining health and caring for three children while his wife worked, Guthrie managed to record 32 reels of tape, with everyday sounds like knocks on the door and his toddler Nora’s voice woven into the recordings.

Anna, Guthrie’s daughter, recalls how he wrote songs amid chaos—on gift wrap, paper towels, or with kids climbing on him. In a 1948 letter to folk music advocate Alan Lomax, he famously wrote: “A folk song is what’s wrong and how to fix it.” Often, he only had time to jot down a title before the idea slipped away.

The “Woody at Home” collection features previously unreleased songs tackling racism (Buoy Bells From Trenton), fascism (I’m a Child Ta Fight), and corruption (Innocent Man), alongside lighter themes like love, religion, and even Albert Einstein—whom Guthrie once met on a train. Nora laughs that her father wrote “no less than five songs about washing dishes.”

One notable track, Old Man Trump (also called Beach Haven Race Hate), criticizes their landlord Fred Trump—father of Donald—for discriminatory housing policies. Another newly released song, Backdoor Bum and the Big Landlord, contrasts greed with generosity. Nora explains: “It’s about how the guy who has everything gives nothing, and the guy who has nothing gives everything.” Her favorite part depicts the landlord arriving in heaven, demanding to “buy this place and kick you out”—a biting commentary on entitlement.

The family later moved to Queens, where an 11-year-old Nora once answered the door to a persistent 19-year-old Robert Zimmerman—the future Bob Dylan. Unimpressed at first (“I was watching American Bandstand!”), she eventually let him in. Dylan, inspired by Guthrie’s autobiography Bound for Glory, later visited him in the hospital where he was battling Huntington’s disease.

Though the 2024 Dylan biopic A Complete Unknown dramatizes their meetings, Nora clarifies that Guthrie wasn’t in a private room but a crowded psychiatric ward. Dylan would bring pens and cigarettes, singing both his own songs and Guthrie’s back to him—a gesture Nora deeply appreciates. By then, Guthrie was severely ill, and Nora reflects: “Because of Huntington’s, I didn’t have a dad in the traditional sense.”Nora sighs as she explains, “He didn’t have what people would call normal conversation skills. We couldn’t talk the way we’re talking now. Physical contact was difficult too—with Huntington’s, your body never stops moving. To hug him, we’d have to hold his arms still. When we went out to eat, people would stare at him like he was drunk, and that was painful.” After becoming Woody’s caregiver, Nora has continued caring for his legacy ever since.

“It happened by accident,” she says, recalling how she was working as a professional dancer when, in 1991, Guthrie’s retiring manager asked her to go through boxes of his belongings. “One of the first things I found was a letter from John Lennon,” she tells me, bringing out the framed note sent to the family in 1975. It reads: “Woody lives and I’m glad.” Next, she discovered the original lyrics to This Land Is Your Land. “It was a treasure trove.”

And there’s still more to uncover. His family hopes to inspire today’s young songwriters—and activists—just as Guthrie once influenced Dylan, Springsteen, and countless others. “I see us as the keepers of the flame,” says Anna. “We keep Woody’s spark alive so that whenever someone wants to ignite their own fire, Woody’s spirit is ready to inspire.”

Deportee (Woody’s Home Tape) is now available on streaming services. Woody At Home, Vol. 1 & 2 will be released on Shamus Records on August 14.