On August 5, 2024, Sheikh Hasina stepped down as Bangladesh’s prime minister and left the country, marking the climax of a student-led uprising that saw unprecedented numbers of women joining street protests.

Women took center stage in the demonstrations, leading marches with sticks and stones and standing firm against riot police and military forces. Their visibility became a defining symbol of a revolution that reshaped Bangladesh’s political and social landscape.

The uprising resulted in an interim government led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus, which has prioritized stabilizing the country. However, despite the political changes, many women still feel their voices are being ignored. In May, thousands participated in the Women’s March for Solidarity, calling on the government to protect women’s rights and safety.

Here, five Bangladeshi women share their experiences over the past year and the changes they believe are still needed.

### Umama Fatema, Student Activist

When Umama Fatema convinced fellow female students at Dhaka University to leave their dorms and join last year’s protests, she had no idea how far the movement would go.

“Everything happened so fast—soon the uprising spread nationwide,” says Fatema, a key organizer of the July protests. “Women turned this into a people’s revolution. Without them, none of it would have been possible.”

But a year later, Bangladesh’s student movement has fractured, and optimism is fading.

“The movement raised crucial questions about governance, accountability, and women’s rights, but they remain unanswered,” Fatema explains. “Instead of addressing them, people are focused on their own political ambitions.”

She says the movement’s toxic atmosphere eventually drove many women away. Until recently, Fatema was the spokesperson for Students Against Discrimination, the group that led the student revolution.

“If women are included just as tokens, they hold no real power,” she says. “Issues like rape and harassment aren’t taken seriously because, in Bangladesh’s power structure, women are still seen as secondary.”

Fatema believes the interim government’s slow progress has fueled frustration. “People expected swift justice, but the process has dragged on. All this talk of reform and justice now feels like empty promises.”

### Shompa Akhter, Garment Worker & Activist

Shompa Akhter has worked in Bangladesh’s garment industry for nearly 20 years. With few opportunities for women in her village in Kushtia, she moved to Dhaka for work.

At a factory on the city’s outskirts, Akhter works long hours for about 15,000 taka (£90) a month—barely enough to survive.

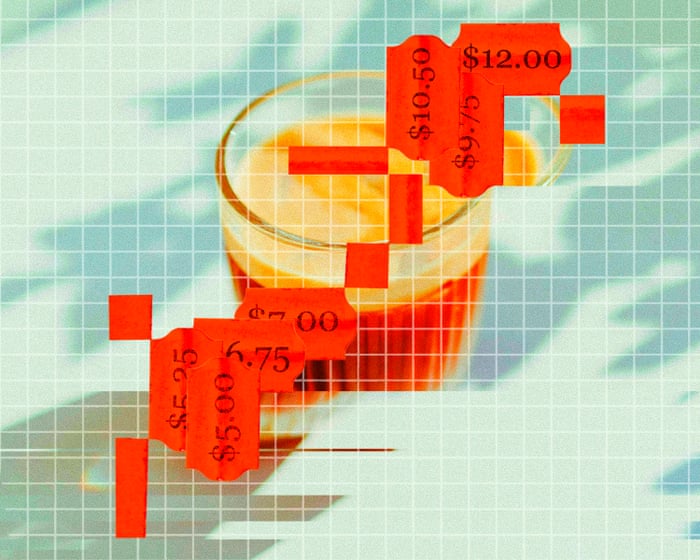

“Prices for rice, lentils, vegetables, oil, and gas have all gone up, but our wages haven’t,” she says. “My children’s school fees are a constant struggle. We skip meals just to pay them. And if anyone gets sick, I have to borrow money from family or loan sharks.”

Akhter recently joined protests demanding better wages and working conditions for Bangladesh’s 4.4 million garment workers, most of whom are women. The garment sector, the backbone of the economy… (text continues)The country’s economy relies heavily on the garment industry, which contributes $47 billion (£35 billion) annually – accounting for 82% of total export earnings.

“We garment workers keep the factories running, yet we’re treated as disposable,” says Akhter. “Our voices matter, and we demand fair wages that reflect our labor and allow us to live with dignity.”

“Being a woman in Bangladesh still means fighting for your place—whether at home, work, or in the community,” she adds. “My dream is for my daughters to grow up in a country where they don’t have to struggle just to be heard. The government must include us in negotiations. Women need a seat at every decision-making table if we want real, lasting change.”

### Triaana Hafiz, Transgender Model

When Triaana Hafiz moved to Dhaka in 2023, she hoped life would be different. Growing up in Khulna, she faced constant discrimination and harassment.

“I knew I was different, and so did everyone else. I tried to stay unnoticed, but society wouldn’t even let me exist quietly,” says Hafiz. “It got so bad that I considered suicide multiple times.”

Her breakthrough came when she landed a modeling job in the capital. “It wasn’t easy, but in Dhaka, I finally felt free to be myself. I found a supportive community that accepted me as a transgender woman.”

When student protests erupted in 2024, she felt hopeful. “The revolution’s main message was an end to discrimination. I wasn’t naive enough to think this automatically included me, but I hoped the younger leaders would be more inclusive.”

Instead, she says, “Discrimination has worsened, with politicians openly spreading transphobic hate.”

Hafiz urges the interim government to protect gender-diverse rights in new laws. “Everyone in the new Bangladesh deserves dignity and security. We should celebrate diversity, not just tolerate it—a country where everyone belongs, regardless of gender, religion, ethnicity, or class.”

### Rani Yan Yan, Indigenous Rights Defender

Rani Yan Yan comes from the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), a region plagued by decades of ethnic conflict, military violence, land seizures, and attacks on Indigenous communities.

The military presence has been linked to human rights abuses, including killings, disappearances, and sexual violence against Indigenous women and girls.

In 2018, Yan Yan was brutally beaten by security forces while helping two girls who had been sexually assaulted. In May of this year, another Indigenous woman, Chingma Khyang, was attacked.

“There is still so much work to be done,” says Yan Yan.She was gang-raped and murdered. “This attack follows the same pattern as hundreds of others over the years, where the perpetrators have faced no consequences,” says Yan Yan. “The interim government must immediately stop this long-standing culture of impunity in the Hill Tracts.”

In June, the human rights group Ain o Salish Kendra warned of the government’s failure to protect women and the collapse of security. The organization has called on the government to send a strong message that such brutality has no place in Bangladesh.

“There is still so much work to do, but first, we must ensure the rule of law is upheld in Bangladesh, with an open and democratic government that answers to all its citizens,” says Yan Yan.

Samanta Shermeen, student activist

Samanta Shermeen was recently elected senior joint convener of the National Citizen Party.

“During the [July] uprising, Bangladeshi women played a strong and active role. But since then, they’ve been pushed aside,” says Shermeen. “If we don’t give women the respect and recognition they deserve, the revolution would have been meaningless.”

Earlier this year, she spoke out against radicals who vandalized a stadium before a women’s football match. “It was a clear act of hatred toward women and a betrayal of Bangladesh’s core values,” Shermeen says.

“Despite this, our women’s national football team just made history by qualifying for the final round of the Women’s Asian Cup for the first time,” she says proudly. “Bangladeshi women are unstoppable. The more you try to hold us back, the harder we fight to succeed. The revolution proved that—and it was only the beginning.”