A U.S. private prison company, CoreCivic, is expanding its immigrant detention operations as ICE arrests rise—while running a federal facility under FBI investigation for widespread drug trafficking and violence, a Guardian investigation reveals.

Some CoreCivic staff are allegedly involved in smuggling drugs into the company-owned Cibola County Correctional Center (CCCC) in New Mexico, which holds federal detainees under a government contract. The facility has faced serious issues, including FBI allegations of extensive drug smuggling—with some guards implicated—and a troubling number of inmate deaths.

Located about an hour west of Albuquerque, Cibola primarily houses U.S. Marshals detainees and local inmates, with ICE detainees making up roughly 30% of the population.

An October 2024 FBI affidavit, obtained by the Guardian, describes a “drug trafficking epidemic” at the facility. The document alleges that some CoreCivic employees smuggled drugs inside, fueling a lucrative trade among detainees that has led to fatal overdoses. FBI informants reported “dirty correctional officers” at Cibola who hid drugs like suboxone and methamphetamine in their boots to bypass security.

The Guardian’s findings are based on hundreds of pages of court records, FBI documents, police reports, 911 logs, coroner’s office files, and lawsuits.

The FBI launched its probe into Cibola last September, targeting gangs and dealers allegedly supplying drugs. That same month, records show CoreCivic pitched the facility to ICE as an ideal expansion site for immigrant detention, offering to allocate a portion of its 1,129 beds.

Yet FBI records contradict CoreCivic’s confidence in the facility, stating the company “struggles to keep CCCC operating safely” amid drug seizures “exceptionally large for a secure federal facility.” It’s unclear whether CoreCivic disclosed the FBI investigation to ICE, as much of the pitch document is redacted. However, FBI records suggest CoreCivic was aware of the probe and cooperated with investigators.

CoreCivic denied the allegations in a statement, calling them “false and misleading,” and emphasized its “zero-tolerance policy” for contraband. The company maintains it provides a safe, humane environment at Cibola while acknowledging that drug smuggling is a nationwide challenge for prisons.This is a widespread challenge that requires ongoing collaboration to prevent.

The company confirmed it provided intelligence to the FBI investigation and expressed gratitude for the efforts of the agencies involved. “We share their commitment to keeping everyone safe,” the company stated.

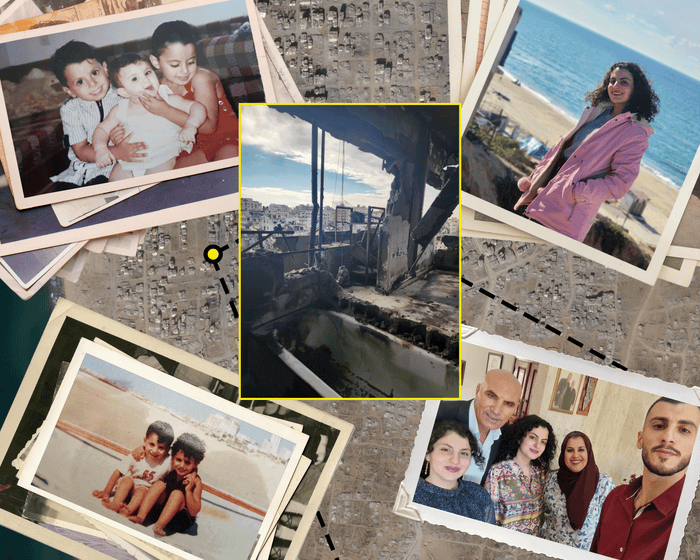

Documents reveal that at least 15 detainees at Cibola have died prematurely since 2018—a notably high number.

Eunice Cho, senior staff attorney with the ACLU’s National Prison Project, said, “Information about these investigations and the number of deaths in custody should be relevant to ICE’s decision on whether to expand its contract with CoreCivic.”

When asked for comment, CoreCivic stated that it takes any deaths in its custody “very seriously” and is “deeply saddened” by such incidents. “The safety and well-being of those in our care, as well as our staff, is our top priority at all facilities, including Cibola County Correctional Center,” the company said.

CoreCivic, based in Tennessee, is the second-largest private prison company in the U.S. It is publicly traded and operates numerous facilities across nearly 20 states.

As the Trump administration continues its mass deportation efforts—shifting focus from the border to detaining and deporting immigrants from within the U.S.—many facilities, especially in high-demand areas, are overcrowded.

Despite ongoing issues, Cibola and similar facilities continue to hold growing numbers of immigrants, and CoreCivic is profiting.

According to company statements and financial reports, CoreCivic has significantly expanded its immigration detention operations in 2025. Seven of its facilities have signed new contracts to hold more ICE detainees, and the company purchased an additional ICE facility from another private prison operator. CoreCivic did not respond to the Guardian’s calculations regarding these numbers.

A May 2025 contract shows that ICE increased its per-bed payment to CoreCivic for detention services at Cibola, though exact figures are redacted.

The FBI declined to comment or confirm whether its investigation is still active, but the New Mexico U.S. Attorney’s Office effectively acknowledged that Cibola remains under scrutiny. “We cannot comment on ongoing investigations or provide details beyond what has been made public,” the office stated.

The U.S. Marshals Service (USMS) did not respond to requests for comment.

Meanwhile, drug problems persist at the facility, according to interviews. While the FBI’s investigation has primarily focused on smuggling within USMS and local county units at Cibola, reports indicate that drug smuggling and use are also occurring in ICE detention areas.

Two ICE detainees at Cibola said they recently witnessed drugs being brought into the facility, sold, and consumed in their unit as recently as May. One detainee described an incident where he and another man were threatened by a dealer after mistakenly receiving an envelope disguised as legal mail—containing contraband “strips of paper” commonly bought by detainees.

The dealer allegedly told them, “I’ll give each of you $500. Accept it, or I’ll kill you.” The detainee recalled, “We stood there with our mouths open.”The items were likely strips of Suboxone or its generic versions containing buprenorphine and naloxone—a prescription medication used to treat opioid addiction that can also produce a mild high. When the detainee accused of dealing drugs realized the envelope had been mistakenly given to one of the men, he threatened them.

“He told us, ‘That paper is mine,'” the man recalled during a call from inside the detention center. “Then he said, ‘I’ll give each of you $500. Take it, or I’ll kill you.’ We were just standing there in shock.”

Fearing for their safety and worried that speaking up might harm their immigration cases, the two men tried reporting the incident to CoreCivic guards, but their complaints were ignored. Word spread, and soon other detainees began taunting them—they had become targets, forced to constantly watch their backs. Days later, the dealer attacked them for trying to report his threat, punching both men and smearing feces on one of them. The Guardian is protecting their identities at their request, as they fear retaliation.

“Last year, we understood that drug issues were mostly limited to the U.S. Marshals’ side,” said Sophia Genovese, a Georgetown University Law Center faculty member and former attorney with the New Mexico Immigrant Law Center (NMILC), which advocates for ICE detainees. “As far as we knew, the only time ICE detainees encountered drugs was when they were accidentally sent to their unit through the kitchen. It was surprising to hear that someone in the ICE unit was the intended recipient—this wasn’t something we’d seen before.”

CoreCivic responded by stating: “We provide all detainees with a thorough grievance process, offering multiple safe and confidential ways to raise concerns.”

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which oversees ICE, strongly denied any drug smuggling within ICE units at Cibola.

“Claims that drug smuggling is happening in the ICE section of Cibola County Corrections Center are false. In fact, there hasn’t been a single report of drugs in that part of the facility,” said DHS assistant secretary Tricia McLaughlin in a statement to The Guardian.

She added: “Any suggestion of substandard conditions in ICE detention centers is untrue. The safety and well-being of those in our custody is a top priority. ICE remains committed to enforcing the President’s mandate to arrest and deport criminal undocumented immigrants.”

Meanwhile, a troubling pattern has emerged at Cibola—at least 15 detainees have died there since May 2018, according to The Guardian‘s findings.

“That’s a disturbingly high number of deaths for one facility in that timeframe,” said Cho. “It points to serious operational failures. Many of these deaths, particularly suicides, appear preventable.”

CoreCivic responded: “Our facilities have trained emergency teams to ensure anyone in distress receives proper medical attention.”

Cibola has operated since the 1990s and was later acquired by CoreCivic.Here’s a rewritten version of the text in fluent, natural English while preserving the original meaning:

In 1998, the Cibola facility opened. It closed in 2016 after CoreCivic lost its contract with the federal Bureau of Prisons following reports of medical neglect and suspicious deaths published by The Nation. However, later that same year, the facility reopened under a new contract with CoreCivic to house federal pre-trial detainees, county inmates, and immigrants for both US Marshals Service and ICE.

Since the start of Trump’s second term, the number of immigrants held at Cibola increased from 160 in January to 224 by late June. Austin Kocher, a Syracuse University researcher who tracks ICE enforcement, reported an average of 405 ICE detainees in late April, though recent numbers show just over 200. The facility can hold up to 1,200 detainees total.

“Our biggest concern has always been the lack of medical care,” said Genovese. CoreCivic claims the facility undergoes “multiple layers of oversight” and is “closely monitored by government partners to ensure compliance with policies.”

One detainee in the ICE section remarked: “I thought the US was a country of laws. But I’ve learned there’s a lot of corruption here.”

While DHS oversight offices inspect the facility and publish reports due to CoreCivic’s ICE contract, Genovese says these inspections are limited and ineffective. The FBI launched an investigation into CoreCivic’s management of Cibola after problems with drug smuggling, violence, and corruption grew so severe that federal judges alerted the New Mexico US Attorney’s office.

FBI records reviewed by The Guardian reveal that over 40 informants—including gang members, drug dealers, and Mexican organized crime figures—exposed a network smuggling drugs like fentanyl, meth, Suboxone, and heroin into the facility. From January to October 2024, authorities seized drugs 43 times inside Cibola, though this was fewer than previous years according to an FBI affidavit.

Gangs involved include the New Mexico Syndicate, Sureños, Paisas, and the Aryan Brotherhood. An FBI agent noted that despite being street rivals, these gangs collaborate inside prisons to distribute drugs. “Gang loyalty comes second to profit,” wrote FBI agent Jordan Spaeth in the affidavit.

Drug prices skyrocket inside the facility—a pound of meth worth $1,000 outside sells for $272,400 inside. One fentanyl pill costs $50, while a Suboxone strip goes for $100. Detainees often pay through outside contacts using CashApp on smuggled phones. One unnamed immigrant confirmed this practice to The Guardian. The FBI found one inmate made $10,000 in under a month just by handling these transactions.Drugs are smuggled into Cibola in several ways. According to the FBI affidavit and confirmed by an immigrant detainee, fake “legal mail” that isn’t inspected by staff often contains drugs. Another method is the “throw-over,” where outsiders toss drug packages into the recreation yard for inmates to collect.

There’s also evidence that CoreCivic staff have been involved in smuggling. One FBI informant claimed a former correctional officer likely brought in 700 fentanyl pills, while another guard reportedly earned $5,000 per drug delivery. A manager at the facility allegedly used inmate work crews to distribute drugs while they delivered food and supplies, according to FBI documents.

In May 2024, a guard caught detainees using meth, confiscated the drugs, and filed a report—despite the manager’s reluctance. Later, the drugs vanished from evidence, photos were deleted, and the report disappeared. The guard believed the manager tried to cover it up. Weeks after this incident, the same manager assigned the guard to a high-security area without proper training. During that shift, two gang members attacked the guard, locking them in a cell. The guard later suspected the manager set up the assault.

CoreCivic fired the manager for disciplinary issues, but no criminal charges were filed. However, in 2023, another guard was sentenced to two years in prison for smuggling meth into the facility.

With starting salaries under $48,000 per year, some guards are tempted by drug dealers offering $3,000 to $6,000 per package. As the FBI noted, a guard smuggling just three packages a week could double their annual income in a month. In one case, a guard admitted to smuggling drugs to avoid losing her home—this was revealed in a lawsuit filed by the family of a woman who overdosed at Cibola.

One shocked detainee told the Guardian, “I thought the U.S. followed strict laws, like they say on TV—that safety mattered here. But now I see there’s so much corruption.”

Meanwhile, ICE detention centers nationwide are overcrowded. The Department of Homeland Security is awaiting funds from a recent spending bill to expand detention capacity, even as controversial new facilities open quickly.

CoreCivic has proposed converting Cibola entirely into an ICE detention center or housing a “mutually agreeable percentage” of ICE detainees. The company insists it remains “dedicated to excellent service” regardless of the population.

(Part 2 continues on Monday.)An investigation into the Cibola County Correctional Center