Da, a 31-year-old Cambodian living in Thailand, has kept her children home from school this week, fearing they might face discrimination. “One of my friends went to buy durian at the market yesterday, and the seller told her she hated Cambodians,” Da says, describing the growing tensions between the neighboring countries.

Days after Thailand and Cambodia announced a ceasefire following a deadly five-day conflict, relations remain fragile, with both sides accusing each other of violating the truce. Meanwhile, online hostility is being fueled by a mix of misinformation, threats, and nationalism.

Dowsawan Vanthong, 50, who volunteers at a temple in northeastern Thailand sheltering evacuees, worries that even if the border reopens, relations may not fully recover. “I can separate ordinary Cambodians from their government or military, but I’m not sure everyone can—especially in the hardest-hit areas,” she says.

At least 43 people were killed in the clashes, the worst violence between the two countries in over a decade.

Normally, people frequently cross the 800km border for trade, work, school, or healthcare. Before the conflict, more than 520,000 Cambodians worked in Thailand, often in low-wage jobs in farming, construction, fishing, and factories. Now, the border is nearly closed, though Cambodians in Thailand can still return home. Thousands have lined up to leave, fearing rising hostility.

Da, who works as a cleaner and asked not to use her real name due to safety concerns, says she must stay in Thailand to pay off debts but feels uneasy. “The kids saw on social media that many Cambodians are going home, so they wanted to too,” she says.

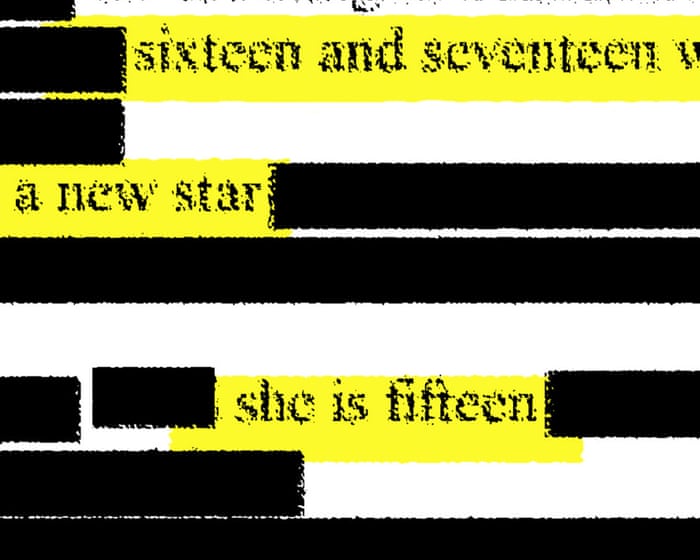

Social media has become increasingly volatile. One viral TikTok clip shows a Thai man slapping a young Cambodian for smiling while being told to warn Cambodia’s former leader Hun Sen not to attack Thailand. Hun Sen later shared the video, cautioning Cambodians in Thailand to stay safe.

Another widely circulated video allegedly shows Thai people assaulting a Cambodian man. When two Cambodian women posted videos stepping on the Thai flag—part of a social media trend—people demanded their deportation.

Thai authorities have urged influencers and young people not to incite violence, but online anger persists.

The two countries have a long history of disputes, including clashes over cultural heritage. In 2003, riots broke out in Phnom Penh after false rumors that a Thai actor claimed Cambodia’s Angkor Wat belonged to Thailand, leading to the Thai embassy being set on fire.

Diplomatic spats and online outrage have flared up repeatedly. Two years ago, Thailand boycotted a kickboxing event in Cambodia after the sport was called “Kun Khmer” instead of “Muay Thai.” Even innocent posts can spark backlash—like when the UK ambassador to Cambodia posted a photo of “Khmer desserts,” prompting Thai users to angrily insist the treats were actually Thai.

This time, social media—far more widespread than during past conflicts—has amplified tensions even further.The fighting in 2008 and 2011 has heightened tensions. Some have objected to the response—a major hospital in Ubon Ratchathani province faced backlash after temporarily refusing new Cambodian patients and announcing stricter zoning for existing ones due to the clashes. Critics called the policy discriminatory, though some online users defended the hospital. One commenter wrote, “Should we heal them just so they can shoot at us again?”

The public mood in Thailand—and pressure on authorities to hold Cambodia accountable for attacks on Thai civilians—could jeopardize the fragile ceasefire.

Political analyst Ken Lohatepanont believes the ceasefire will likely hold for now, but the long-term outlook remains uncertain. “Thailand and Cambodia still have many border issues to resolve, as none of the core disputes have been addressed yet,” he said. Both countries continue to rely on conflicting maps to define the border.

Da, a resident of Rayong province far from the conflict zone, mostly stays home, only venturing out for food and work. “Both sides have made mistakes—they need to find a peaceful way to talk,” she says. “I want things to return to normal, for the borders to reopen so Thais and Cambodians can reunite.”