In 1991, four teenage girls were brutally murdered in Austin, Texas. Their bodies were left to burn in a fire that destroyed the yogurt shop where two of them worked—along with crucial evidence.

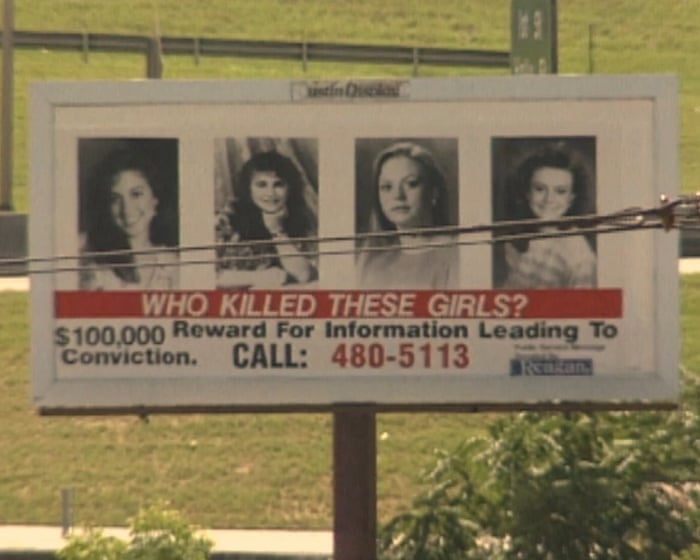

For anyone who lived in Austin at the time, the memories of this case remain raw and vivid—not just because of the horrific crime itself, but also because of how the community rallied around the victims’ families. People marched with signs, put up billboards, and made buttons and coffee mugs, all bearing the same haunting question that remains unanswered to this day: Who killed these girls? True to Austin’s spirit, local artists even wrote a song: We Will Not Forget.

Barbara Ayres-Wilson, the mother of two of the victims, reflects in archival footage featured in The Yogurt Shop Murders: “Americans, the way we deal with grief—we had to make a marketing opportunity out of everything.” Even in her grief, she recognized the strange irony of how tragedy can become commodified.

Margaret Brown’s four-part docuseries follows Ayres-Wilson’s lead, balancing the emotional devastation of the crime with broader observations about the cultural response. The series doesn’t just focus on the trauma endured by the victims, their families, and those close to the case—it also examines the flaws in the justice system, including coerced false confessions that created new victims. And, perhaps most strikingly, it questions the nature of true crime storytelling itself, even as The Yogurt Shop Murders participates in that genre.

Brown crafted a layered and complex documentary by resisting the usual true crime tropes—like voyeuristic fascination with gruesome details. “I wasn’t really interested in this because of the ‘true crime-iness’ of it,” she tells the Guardian. The project was brought to her by executive producers Dave McCary and Emma Stone, but what drew her in was how deeply personal the story felt.

“It’s part of the fabric of this city,” says Brown, who lives in Austin (though she’s originally from Mobile, Alabama, where her acclaimed documentary Descendant is set). The victims—17-year-olds Eliza Thomas and Jennifer Harbison, Jennifer’s 15-year-old sister Sarah, and their 13-year-old friend Amy Ayers—were just a few years younger than Brown at the time. She had friends who knew them, went to school with them, or even cheered alongside them. The tragedy still looms large in her circles.

When Brown first saw archival footage from the case, she was struck by what she describes as a “David Lynch vibe.” “It was like the same hair from Twin Peaks,” she explains. “You could immediately see a version of what the film could be—the counterculture of Austin back then, when Slacker came out… I thought, ‘Oh, I could make a David Lynch movie that’s a documentary.’”

Lynch’s work often explores the darkness beneath seemingly pleasant surfaces, and the collision of different worlds within a single place. That eerie contrast fits this case—where horror erupted in a cheerful frozen yogurt shop, a popular teen hangout, and where outsiders—particularly those from outside Austin—became entangled in the investigation.

The Yogurt Shop Murders doesn’t just recount a crime—it examines how a community processes grief, how justice can falter, and how stories like this become part of our collective memory.The investigation swept up all kinds of suspects—from local outcasts to those who frequented Austin’s hidden corners—revealing the deep social and class divides in the city. It also highlighted the cultural landscape of early-90s Austin, where, as Brown describes, “country guys and counterculture people” coexisted.

“Austin has always been this mix of a college town and a cowboy place,” Brown says, noting how both groups united as part of Willie Nelson’s audience. “They all go see Willie.”

But Brown’s perspective on the story shifted dramatically after her first interview with the victims’ families left her emotionally devastated.

“I felt their pain so deeply,” she recalls. “Sean [Amy Ayers’s older brother] was terrified of forgetting his sister—her voice, her presence. The way he talked about losing those memories was heartbreaking. I just thought, I cannot mess this up.”

She realized she couldn’t approach the story as just another slick, stylized project. Instead, she became more interested in how people cope with loss—something universal that everyone understands. “The story was so dark,” she says. “To really sit with that darkness, I needed some kind of redemption to keep going.”

The Yogurt Shop Murders explores the complex role of storytelling in processing trauma. For the victims’ families, recounting the tragedy became a way to preserve their loved ones’ memories while seeking justice. Ayres-Wilson, for instance, didn’t fully grasp her grief until she had to explain what happened to others.

Eliza Thomas’s younger sister, Sonora, who grew up feeling isolated because people avoided bringing up the tragedy, even offered an unexpected defense of true crime. “These shows aren’t just for the curious,” she tells Brown. “They give victims a way to tell stories no one else wants to hear.”

Brown suggests another reason true crime resonates, especially with women: “For some, it’s about solving the puzzle. But for women, it’s something deeper, more primal.” She also acknowledges the genre’s exploitative side, adding, “It’s not just one thing—it’s complicated.”

The series also examines how the case affected others. Detectives working on it for years developed PTSD from piecing together the crime’s narrative. Claire Huie, a filmmaker who once tried to document the story, abandoned the project—and her career—because of its emotional toll. Much of her unused footage, including interviews with families, detectives, and Robert Springsteen (one of the wrongly convicted men), appears in Brown’s series.

Springsteen, who didn’t participate in the documentary, was sentenced based on a coerced confession—one of many in the case. Brown and her editor, Michael Bloch, take a surreal, almost Lynchian approach to recreating the nightmarish interrogations where officers fed suspects narratives to fill in gaps.

In a series where…Victims’ families often turn to storytelling to preserve their memories, but these scenes—revealing how fragile, unreliable, and deceptive memory can be—create a chilling contrast.

“You can’t make a show like this without questioning your own shifting memories,” says Brown. “I might recall something and wonder: ‘Is that real? Did it actually happen? Or do I just want it to be true?’”

“I’ve always been drawn to complexity—how something can be positive in one sense yet carry a darker side. Memory is the perfect example. It can be both a trap and a comfort.”

The Yogurt Shop Murders premieres on HBO on August 3 and will stream on Max. A UK release date will be announced soon.