At first glance, there’s a world of difference between greasy Friday night chips and fresh Mediterranean tomatoes. But scientists have made a surprising discovery – these two foods share a deep ancestral connection.

Groundbreaking research reveals that potatoes evolved from a tomato-like ancestor nearly 9 million years ago. Wild tomatoes from the Andes crossbred with a plant called Etuberosum, mixing their DNA through hybridization to create an entirely new plant lineage.

“Tomato is the mother, and Etuberosum is the father,” explained Professor Sanwen Huang, who led the study at China’s Agricultural Genomics Institute in Shenzhen. “But this wasn’t obvious at first.”

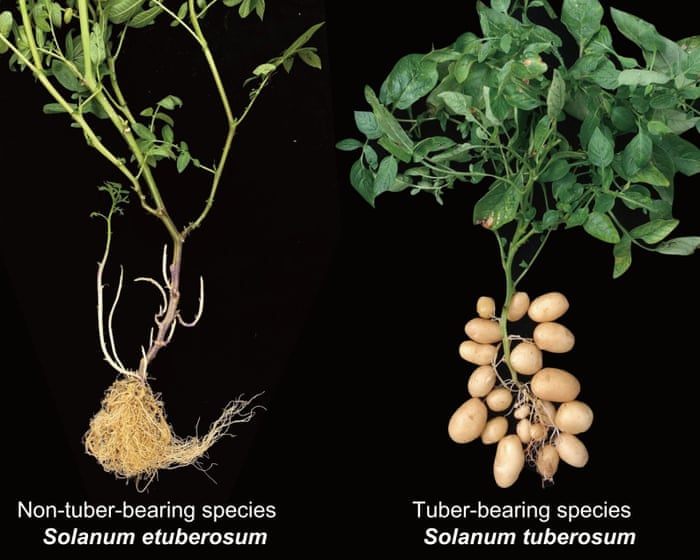

Above ground, potato plants look nearly identical to Etuberosum. The real difference lies underground – while Etuberosum has thin stems, potatoes develop the starchy tubers that feed millions worldwide.

To solve this mystery, scientists turned to tomatoes. Though they don’t form tubers, their genetic makeup is strikingly similar. “Tomatoes, potatoes, and Etuberosum are closely related, along with eggplants and tobacco,” said Huang. “So we dug deeper.”

The team, publishing their findings in Cell, analyzed 450 cultivated potato genomes and 56 wild species – one of the largest genetic studies of wild potatoes ever conducted. They identified two key genes responsible for tuber formation: SP6A from tomatoes and IT1 from Etuberosum. Alone, neither gene creates tubers, but when combined in potatoes, they trigger the process that turns underground stems into starchy, edible tubers.

“This study is revolutionary,” said Harvard evolutionary biologist James Mallet. “It shows how hybridization can spark entirely new organs – and even new species.”

Potatoes inherited a robust mix of genes from both parents, making them hardy and adaptable. Their tubers store energy, helping them survive harsh winters or droughts and allowing them to reproduce without seeds or pollinators. Instead, new plants sprout from buds on the tubers.

This adaptation helped potatoes thrive in the high-altitude Andes. Over time, they diversified into hundreds of wild varieties. Indigenous Andean farmers later domesticated them, selecting those with the largest, tastiest tubers.

“In the Andes, there are hundreds of potato varieties,” said Dr. Sandra Knapp of London’s Natural History Museum. “In Europe, we mostly grow just one species – Solanum tuberosum.”

Potatoes traveled globally aboard Spanish ships in the 1500s. Initially met with suspicion (they grew underground and weren’t mentioned in the Bible), their nutritional value and resilience soon won people over, making them a worldwide staple.

Today, natural hybridization between potatoes and their closest relatives is unlikely – they’ve evolved too far apart. But scientists are exploring artificial methods to create new varieties.

“We’re working on making potatoes reproduce by seeds,” said Huang. “We’re also inserting the IT1 gene into tomatoes to see if they can grow tubers.”

For now, these experiments are just beginning. But if successful, tomatoes might not just be part of the potato’s past – they could shape its future too.