If I told you I’ve played football for 15 years, you’d probably assume I’m decent. Unfortunately, I’m not. I have three left feet and a not-very-convincing shot on goal. Despite all the years I’ve put into the sport, these things show little to no improvement.

I play football for the joy of it: the rush of the first whistle; the exhilaration of making a successful tackle or a clever pass; and the feeling of all fears and concerns melting away the moment the game starts. So until recently, the fact that I’m so bad at it seemed, at worst, incidental. I grew up at a time when football was largely considered a men’s sport. In the 90s, there were about 80 girls’ football clubs in England (there are more than 12,000 now); there wasn’t a women’s premier league until 1994; and by the time I was in my 20s, boring jokes about women knowing the offside rule were wheeled out with disappointing regularity. As someone who still remembers the feeling of getting kicked off the pitch by the boys as soon as I entered year 3, I’ve always just felt blessed to play.

But after a while, I did start to find it a bit depressing being so comically awful at something that I love. I’m fed up with starting team after team for beginners, only to watch all those who have never kicked a ball before get better than me by the end of the season.

So this year, I wondered if I could break the cycle: could someone like me—a player so awful at football that if you watched me play you would truly, honestly, gasp—ever get any better? Is getting better at sport something that can happen in your mid-30s, after you’ve had kids, especially if it’s something you’ve thrown hours into but at which you seem to be cosmically ungifted? I decided I would try.

“It’s going to be a battle,” says my coach during our first phone call. It’s a sunny day in August and I’m sitting in the garden with my dog curled at my feet, but I suddenly feel a shadow of a cloud pass over. At least he’s honest, I think.

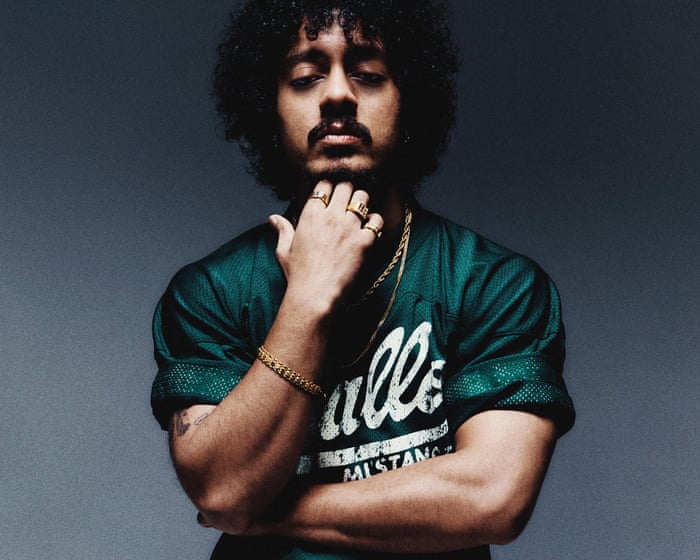

I know Wayne Phillips from his work with women’s teams, and I’ve always been impressed with how far he can take players. Phillips asks me to come to our first session with a few ideas on my strengths and weaknesses. I come with mostly weaknesses: I can’t cross or shoot properly; I freeze whenever I have to make a basic judgment call under pressure; and I can’t run very fast while keeping the ball. I am good at anticipating where the ball will go, and getting there in good time. I also think I’m a good team player, always cheering on my team and getting overly excited at even the most lukewarm attempt from one of my teammates on goal.

Phillips believes that someone’s footballing ability can be broken down into a few core principles. First is their physicality: are they fast? Strong? Prone to injury? Then their technical skill—how well they pass, dribble, shoot and tackle. Social attributes are just as important: I’ve played many a football match where a skilled player refuses to pass, and find it frustratingly similar to that episode of Frozen Planet where huge bison find themselves demolished by a pack of wolves because they just don’t know how to work together. Finally, there’s a player’s psychology: their resilience, concentration and ability to manage their emotions.

We agree to a strict schedule of training: one-on-one coaching sessions once a week, alongside group training and weekly matches. Phillips will map my progress, and make a plan tailored to my strengths and weaknesses. I promise to work on my strength and fitness.

In our first session, we do a drill where I have to dribble and turn, but I can barely keep hold of the ball. We begin a short set of drills…The session focuses on tricks to deceive and misdirect. We start with the Cruyff turn, where you plant one leg and begin to move as if running in one direction, while subtly tapping the ball the other way. We also practice step-overs and simple feints. I struggle terribly with all of it.

By the end of our first session, I feel the level has been set at a cruelly unrealistic standard. I hope Phillips agrees and that we can just stick to dribbling and passing in future.

They say in therapy that the reason you think you’re there is never the real reason. The same goes for football training. I thought I came to sharpen some core skills, but three weeks in, I’m realizing the real reason I’m here is that I’ve painted myself into a corner, and it’s held me back.

I’ve often treated football like an uninterested lover: happy to say I’m in it for fun, but too nervous to take my problems with it seriously, fearing disappointment. I’ve always played in defense, convinced it was a reactive, less technical position where I could barge and shove my way to decent results without refining my footwork. Taking the ball forward, trying to score or set up a goal—I’ve always assumed those were jobs for someone else.

Phillips notices this immediately. He sees how I only know how to receive the ball in the most basic stance: square on and moving in a straight line. To improve, he explains, you have to create angles, receive and pass from any position, and take the ball in surprising directions. So we begin expanding my repertoire. Wayne has me practice receiving the ball on my back foot so I can turn quickly. He teaches me the reverse pass, where you send the ball at a seemingly impossible, counterintuitive angle at the last moment. Gradually, I learn to receive a pass while in motion, rather than standing still.

At group training, I try out these new skills. We also work on attacking, which really opens my mind. I learn to pin my opponent back to prevent them from getting the ball, instead of waiting for them to receive it. These concepts are exciting and new, and I tell myself that if I can master them, good things will follow.

But it’s not easy. Most weeks, I play a match with my team and feel embarrassed when they ask when they’ll see the results of my training. “Not yet,” I say—leaving out my doubt that they ever will.

“Can we have a chat?” I ask Phillips one Sunday before our usual session. We’re just over a month into training, and I feel childish bringing up problems so soon, like a student who says she doesn’t understand the assignment without even trying.

But I have been trying, and I seem to be getting worse. The group trainings where I once felt competent now leave me feeling tragically behind. In matches, I feel I’ve actively declined, making rookie errors and suddenly unable to shoot or pass accurately. It’s laughable that just a few weeks ago, Phillips was teaching me new turns and tricks when I still can’t do basics like keeping the ball after it’s passed to me.

“You’re reinventing yourself,” says Phillips. “The process of improving requires setbacks.”

We move to our weekly drills, where I struggle to pass the ball into the top-left corner of the pitch and can’t dribble effectively.I stumble around cones and trip over my own feet when trying to receive a pass. None of this feels like reinvention, I think. It just feels like I’m getting worse.

But I try to remember something. “The way you talk to yourself is invasive,” says Phillips. “It seeps into all your decision-making. I’m not telling you not to be critical, but all that ‘I’m rubbish’ talk? Just leave it at the door.”

That, at least, feels like something I can work on.

My friend has given me a new metaphor, related to playing the trumpet. Many good trumpet players reach a crossroads if they want to turn professional. At amateur levels, many students are taught “a bit of a poor mouth position,” as my friend Barbara puts it. This mouth position is called your embouchure, and if you want to go pro, it’s best to relearn it.

“It’s like you’re going through a process of fixing your embouchure,” Barbara tells me.

I take Barbara’s lesson to heart, and eventually, something clicks. I realize that over the past few weeks, I’ve been trying to dictate the direction of play rather than just reacting to it. In doing so, many of my old football mistakes have crept back in.

A few years ago, playing football in New York, I complained that I could never receive the ball without it shooting off in another direction. A teammate explained that my foot was too “hard”—so I had to learn to cushion the ball with my foot. This and other early errors had returned to my game. While my brain started focusing on new things, like how to take a shot on goal, I stopped focusing on some fundamental aspects of passing, such as keeping my head and body over the ball. And in trying to think ahead, I neglected basics like: don’t pass the ball right in front of your own goal, and always receive the ball with the inside of your foot.

They say the first step to improving is realizing you have a problem—and once I realize this, my game does improve. In one group session, I score a goal with a header. In a one-on-one, I start combining tricks in sequences: running with the ball, doing a step-over, turning, dragging the ball back with the center of my foot before running off and doing a Cruyff turn. I learn to feint, double feint, and double stepover. I even start wondering if I should become a striker.

“I have to admit,” Phillips says after a successful training session, “when I first saw you on the ball—the way you handled it—I thought, how am I going to deal with this?” Looking at me now, he says he feels proud. “Every action you made today was clean,” he adds.

There was a period about four years ago when I decided I wanted to be a good footballer. After playing for over a decade, I’d joined a very good seven-a-side team in New York and wanted to be like them. So I started going to the park every day. I practised kick-ups, improving from barely getting the ball off the ground to one kick-up, then six or seven. I passed the ball against the wall relentlessly, trying to improve my passing and dribbling. I did this most days for a year. And even though I still wasn’t good at football, I did improve somewhat.

Since I started training with Phillips, time has been the elephant in the room. I was seven months out from giving birth to my second child when I contacted him, still breastfeeding and more strapped for time than ever. I can’t get better by throwing endless hours at something anymore.

But during our last session, I’m pleased to see that putting in carefully cultivated hours, wherever I can, has made a difference. We do a drill where I have to keep…I keep the ball and get past Phillips using my new misdirection skills. I win almost every time.

“You take your life seriously,” Phillips says at the end of the session, which surprises me. He’s referring to how I’ve been running on my lunch break to get fitter, and going to yoga and the gym to avoid injury. I had seen these things as necessary overcompensation for my lack of skill, so it’s nice to hear someone reframe it. When he puts it all together, it suddenly feels impressive. “You know what goals you have for yourself. And you make them happen.”

To finish our work together, Phillips comes to watch me play in a match. It’s brutal—I play mixed five-a-side, which is fast-paced and relentless. In this particular match, all the guys on the other team are about 6’3″ and able to lob the ball at the net from a distance. It’s not quite the ending I had in mind for my last match under Phillips’ supervision, but as I walk off the pitch, muddy boots in hand, I feel accomplished. Phillips is right. I might not be the best footballer, but I set myself the goal to get better, and in the end, maybe—just maybe—I did it. That feels worth it.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about improving at football in your mid30s designed to sound like questions from a real person

Mindset Starting Point

Q Is it even possible to get significantly better at football in your mid30s

A Absolutely While you may not become a professional you can completely transform your game Your focus shifts from raw athleticism to smarter play better technique and superior fitness

Q Im starting from a low skill level Is it too late for me

A Not at all Many people pick up sports later in life A beginners mindset can be an advantageyou have no bad habits to unlearn and can build a solid foundation correctly

Q How do I deal with feeling embarrassed or slow compared to younger players

A Focus on your own progress not comparison Communicate your commitment to learning Most players respect effort and a positive attitude more than flawless skill

Training Improvement

Q Whats the single most important thing I should work on first

A First touch A good first touch gives you more time and makes everything else easier Practice controlling passes from different angles and speeds

Q How can I improve my fitness without getting injured

A Prioritize consistency over intensity Mix footballspecific cardio with strength training and always include a proper warmup and cooldown

Q I dont have much time Whats an efficient way to practice

A Dedicate 2030 minutes 23 times a week to solo wall work Pass against a wall and control the return This builds passing accuracy first touch and weak foot ability with minimal time commitment

Q How do I get better game intelligence or vision

A Watch more football analytically Pick a player in your position and follow only them for a full game Notice their positioning off the ball and their decisions before they receive a pass

Q Should I focus on one position

A Yes especially at first Mastering one role lets you understand specific responsibilities and build a specialized skillset making you a more reliable teammate

Practicalities Playing