This CSS code defines a custom font family called “Guardian Headline Full” with multiple font weights and styles. It specifies the font files in different formats (WOFF2, WOFF, and TrueType) and their online locations for the browser to download and use. The font includes light (300), regular (400), medium (500), and semibold (600) weights, each with normal and italic styles.@font-face {

font-family: Guardian Headline Full;

src: url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Bold.woff2) format(“woff2”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Bold.woff) format(“woff”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Bold.ttf) format(“truetype”);

font-weight: 700;

font-style: normal;

}

@font-face {

font-family: Guardian Headline Full;

src: url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BoldItalic.woff2) format(“woff2”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BoldItalic.woff) format(“woff”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BoldItalic.ttf) format(“truetype”);

font-weight: 700;

font-style: italic;

}

@font-face {

font-family: Guardian Headline Full;

src: url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Black.woff2) format(“woff2”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Black.woff) format(“woff”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Black.ttf) format(“truetype”);

font-weight: 900;

font-style: normal;

}

@font-face {

font-family: Guardian Headline Full;

src: url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BlackItalic.woff2) format(“woff2”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BlackItalic.woff) format(“woff”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BlackItalic.ttf) format(“truetype”);

font-weight: 900;

font-style: italic;

}

@font-face {

font-family: Guardian Titlepiece;

src: url(https://interactive.guim.co.uk/fonts/garnett/GTGuardianTitlepiece-Bold.woff2) format(“woff2”),

url(https://interactive.guim.co.uk/fonts/garnett/GTGuardianTitlepiece-Bold.woff) format(“woff”),

url(https://interactive.guim.co.uk/fonts/garnett/GTGuardianTitlepiece-Bold.ttf) format(“truetype”);

font-weight: 700;

font-style: normal;

}

@media (min-width: 71.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive {

margin-left: 160px;

}

}

@media (min-width: 81.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive {

margin-left: 240px;

}

}

.content__main-column–interactive .element-atom {

max-width: 620px;

}

@media (max-width: 46.24em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-atom {

max-width: 100%;

}

}

.content__main-column–interactive .element-showcase {

margin-left: 0;

}

@media (min-width: 46.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-showcase {

max-width: 620px;

}

}

@media (min-width: 71.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-showcase {

max-width: 860px;

}

}

.content__main-column–interactive .element-immersive {

max-width: 1100px;

}

@media (max-width: 46.24em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-immersive {

width: calc(100vw – var(–scrollbar-width));

position: relative;

left: 50%;

right: 50%;

margin-left: calc(-50vw + var(–half-scrollbar-width)) !important;

margin-right: calc(-50vw + var(–half-scrollbar-width)) !important;

}

}

@media (min-width: 46.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-immersive {

transform: translate(-20px);

width: calc(100% + 60px);

}

}

@media (max-width: 71.24em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-immersive {

margin-left: 0;

margin-right: 0;

}

}

@media (min-width: 71.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-immersive {

transform: translate(0);

width: auto;

}

}

@media (min-width: 81.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-immersive {

max-width: 1260px;

}

}

.content__main-column–interactive p,

.content__main-column–interactive ul {

max-width: 620px;

}

.content__main-column–interactive:before {

position: absolute;

top: 0;

height: calc(100% + 15px);

min-height: 100px;

content: “”;

}

@media (min-width: 71.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive:before {

border-left: 1px solid #dcdcdc;

z-index: -1;

left: -10px;

}

}

@media (min-width: 81.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive:before {

left: -10px;

}

}For the interactive main column, a left border is added before the content, positioned 11 pixels to the left. Elements within this column have no top or bottom margin but include 12 pixels of padding on both top and bottom. When a paragraph is followed by an element, the padding is removed, and margins of 12 pixels are applied instead. Inline elements are limited to a maximum width of 620 pixels, which also applies to inline figures on screens wider than 61.25em.

Custom properties define colors for various elements, such as dateline, header border, caption text, and background, with a feature color set to red and a new pillar color defaulting to the primary or feature color. Elements with the atom class have no padding.

For the first paragraph following specific elements or a horizontal rule in different content areas, a top padding of 14 pixels is added. The first letter of these paragraphs is styled with a large, bold, uppercase font in a specific color, floating to the left with a margin and vertical alignment.

Additionally, paragraphs immediately after a horizontal rule in these areas have no top padding.Pullquotes within specific content areas have a maximum width of 620 pixels.

Showcase element captions in main content and article containers are positioned statically with full width, also capped at 620 pixels.

Immersive elements span the full viewport width minus the scrollbar. On screens up to 71.24em wide, these elements are limited to 978 pixels, with caption padding of 10px on smaller screens and 20px on medium ones. Between 46.25em and 61.24em, the maximum width is 738 pixels. Below 46.24em, immersive elements align to the left edge with adjusted margins and 20px caption padding on medium screens.

For furniture wrappers on larger screens (61.25em and up), a grid layout is used with defined columns and rows. Headlines feature a top border, meta sections have top padding, and standfirst elements include styled links with underlines that change color on hover. Initially, the first paragraph in standfirst has a top border, which is removed on wider screens (71.25em and above). Figures within the wrapper have no bottom margin and a left offset, with inline elements constrained to 630 pixels. On the largest screens, the grid adjusts its column structure for better layout.The layout uses a grid with specific columns and rows for different screen sizes. On larger screens, the grid adjusts to have three equal columns for the title, headline, and meta sections, followed by five for the standfirst, and eight for the portrait, with row heights set as fractions. A thin line appears above the meta section, and the standfirst has a vertical line on its left side.

Headlines are bold and change in size and width depending on the screen: up to 620px wide and 32px font on smaller screens, and 540px wide with a 50px font on larger ones. Some decorative lines are hidden on bigger screens, and social sharing and comment elements have borders matching the header’s color.

The standfirst text is normal weight, 20px in size, with padding at the bottom, and it’s shifted slightly to the left with a left padding. Main media images fill the width and adjust margins for different screen sizes, with captions positioned at the bottom with a background color and custom text color. On very small screens, the media spans the full viewport width minus the scrollbar.The furniture wrapper sets a dark background and adjusts margins and padding for different screen sizes. On larger screens, it adds decorative sidebars. Headlines are styled with bold, light gray text, and meta information uses similar colors. Social media buttons feature a distinct color that changes on hover, switching the text and background colors for contrast. Captions are hidden by default but can be toggled with a button, and various elements adapt their visibility and layout based on screen width and other conditions.Elements with the class “furniture-wrapper” and their children have specific styling rules:

– Meta section links are colored using a custom property for the pillar color or a dark mode feature, with the same color applied on hover for both text and underline.

– Standfirst links have no border, use the pillar color or dark mode feature for text, remove background images, and feature underlines with a 6px offset and a header border color. On hover, the underline color changes to the pillar color or dark mode feature.

– Standfirst paragraphs and list items are colored light gray (#dcdcdc).

– For larger screens (min-width: 61.25em), the first paragraph in the standfirst has a top border, which is removed at even larger breakpoints (min-width: 71.25em).

– Pseudo-elements (:before and :after) are used to create sidebars with dark backgrounds and borders, adjusting their width and position based on viewport size and scrollbar width for various screen sizes.

– Keylines and social/comment elements in the meta section use the header border color for strokes and styling.The comment section has a border color that matches the header’s border color.

In articles, level-two headings have a light font weight of 200. However, if a level-two heading contains a bold element, it uses a heavier font weight of 700.

Additionally, the Guardian Headline Full font family is defined with various styles and weights, including light, regular, medium, and semibold, each available in normal and italic versions. These fonts are sourced from specific URLs in WOFF2, WOFF, and TrueType formats.This CSS code defines several font families and their variations for the Guardian website. It specifies different font weights and styles (like bold, italic, semibold, black) for the “Guardian Headline Full” font, each with multiple file formats (WOFF2, WOFF, TTF) for cross-browser compatibility. Additionally, it includes the “Guardian Titlepiece” font in bold.

The code also sets up CSS custom properties (variables) for colors, adjusting them for dark mode on iOS and Android devices. It includes media queries to handle dark mode preferences and applies specific styling to the first letter of paragraphs in article containers on iOS and Android platforms, particularly when they follow certain elements like atoms or sign-in gates.For Android and iOS devices, the first letter of the first paragraph in standard and comment articles is styled with a secondary pillar color. The article header height is set to zero, while the furniture wrapper has padding of 4px on top, 10px on the sides, and none at the bottom.

Content labels within the furniture wrapper use a bold, capitalized font from the Guardian headline family in the new pillar color. Headlines are 32px, bold, with 12px bottom padding and a dark gray color.

Images in the furniture wrapper are positioned relatively, with a top margin of 14px, no bottom margin, and a left margin of -10px. Their width spans the full viewport minus the scrollbar width, and their height adjusts automatically. Inner figure elements, images, and links inside these figures inherit the same styling.For Android devices, images within article containers have a transparent background and adjust their width to the full viewport minus the scrollbar, with automatic height.

On both iOS and Android, the standfirst section in article containers has top and bottom padding, with a negative right margin. The text inside uses specific font families, and links are styled with a particular color, underlined with a custom offset and color, and without a background image or border. When hovered over, the underline color changes to match the link color.

Additionally, the meta section in article containers on iOS and Android is also styled.For Android devices, remove the margin from the meta section in standard and comment article containers.

On iOS and Android, set the color of bylines and author links in feature, standard, and comment articles to the new pillar color. Also, remove padding from the meta miscellaneous section and set the stroke color of its SVG icons to the new pillar color.

For caption buttons in showcase elements, style them to display as flex containers with 5px padding, centered alignment, 28px dimensions, and positioned 14px from the right.

Set the article body padding to 0 on the top and bottom, and 12px on the left and right for both iOS and Android in feature, standard, and comment articles.For iOS and Android devices, in feature, standard, and comment article containers, non-thumbnail and non-immersive images within the article body will have no margin, a width calculated as the full viewport width minus 24 pixels and the scrollbar width, and an automatic height. Their captions will have no padding.

Immersive images in these containers will span the full viewport width minus the scrollbar width.

Quoted text in the article body will display a colored marker using the new pillar color.

Links in the article body will be styled with the primary pillar color, underlined with an offset, and use the header border color for the underline. On hover, the underline color changes to the new pillar color.

In dark mode, the furniture wrapper’s background will be set to a dark gray (#1a1a1a).For iOS and Android devices, the following styles apply to feature, standard, and comment article containers:

– Content labels use the new pillar color.

– Headline text uses the header border color and has no background.

– Standfirst paragraphs and links use the header border color.

– Author names and links in the meta section use the new pillar color.

– Miscellaneous meta icons use the new pillar color for their stroke.

– Showcase image captions use the dateline color.

– Quoted blockquotes in the article body…For iOS and Android devices, the text color of quoted blocks in article bodies is set to a specific pillar color.

Additionally, the background color for various article content sections on both iOS and Android is changed to a dark background, overriding any other styles.

Furthermore, on iOS devices, the first letter following certain elements in article bodies is styled with a specific appearance, ensuring consistency across different article types and interactive content.This CSS code targets the first letter of paragraphs that follow specific elements within various article containers on iOS and Android devices. It applies to different sections like the main article body, feature body, comment body, and interactive content areas, ensuring consistent styling for drop caps or initial letter formatting across the platform.This CSS code defines styles for specific elements on Android and iOS devices. It sets the color of the first letter in certain paragraphs to white or a custom variable, adjusts padding and margins for standfirst elements in comment articles, and styles headings with a 24px font size.

For caption buttons, it applies different padding values on iOS and Android. In dark mode, it changes colors for follow text, icons, standfirst text, links, and bylines to lighter shades and specific pillar colors. A dark background color is set to #1a1a1a.

Additionally, it hides article headers by making them fully transparent on both operating systems, while keeping furniture wrappers visible.For iOS and Android devices, the furniture wrapper in feature, standard, and comment article containers has no margin. Within these, content labels use a new pillar color or a dark mode feature color. Headlines are set to a light gray color (#dcdcdc) and are important. Links in article headers or those with the data-gu-name attribute “title” adopt the new pillar color or dark mode feature color.

Before meta sections or elements with the data-gu-name “meta,” a repeating linear gradient background is applied using the header border color to create a dashed line effect. Bylines within meta sections are displayed in light gray (#dcdcdc).For iOS and Android devices, links within the meta section of feature, standard, and comment articles are styled with a color that uses the new pillar color or a dark mode feature as a fallback.

Similarly, SVG icons in the miscellaneous meta area have their stroke set to the same color variable.

Alert labels in these sections are displayed in a light gray color (#dcdcdc) and override any other styles.

Icons represented by spans with a data-icon attribute also adopt the new pillar color or the dark mode feature alternative.For iOS and Android devices, the color of specific icons in the meta section of feature, standard, and comment articles is set to a new pillar color or a dark mode feature color.

On larger screens (71.25em and above), the meta section in these articles displays a top border using the new pillar color or the default header border color. Additionally, the meta miscellaneous elements are adjusted to have no margin except for a left margin of 20 pixels.

Paragraphs and unordered lists within the article body are constrained to a maximum width of 620 pixels for both iOS and Android across all article types.

Blockquotes with the “quoted” class in the article body’s prose section also receive styling for iOS and Android in feature, standard, and comment articles.For quoted blocks on iOS and Android, the color before the quote uses a secondary theme color.

Links within articles on iOS and Android are styled with the primary theme color, featuring an underline 6 pixels below the text in a light gray color. When hovered over, the underline changes to the secondary theme color.

In dark mode, the color for quoted blocks and links switches to a dark theme color, and the hover underline also adopts the dark theme color.

For app rendering, various text and icon colors are defined using theme variables, including follow text, standfirst elements, bylines, and meta lines. The byline text color is set to a new theme color, and sponsor logos are inverted in light mode.

—

View image in fullscreen

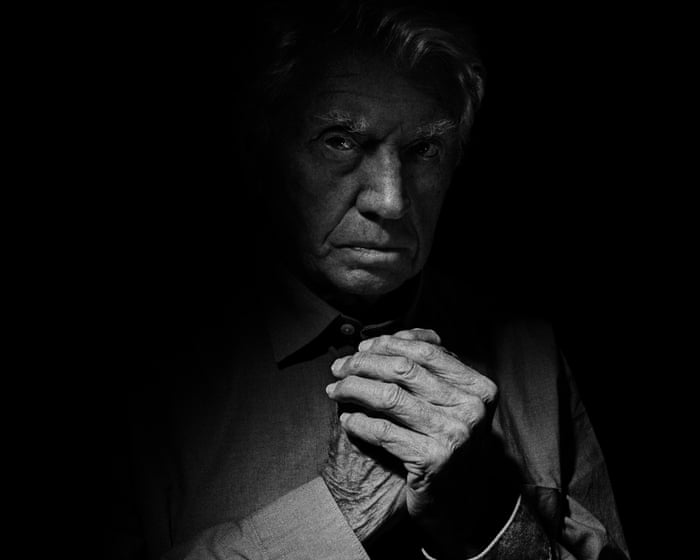

Don McCullin at his Somerset home, October 2025. War photographers aren’t expected to live to 90. “Fate has had my life in its hands,” says McCullin. Throughout his seven decades documenting wars, famines, and disasters, he has been captured and narrowly escaped snipers, mortar fire, and other dangers. What does it feel like to be a survivor? “Uncomfortable,” he admits. It’s no surprise he finds peace in the serene still lifes he creates in his shed or the scenes he captures in the Somerset countryside.

McCullin takes pride in overcoming the extreme poverty of his upbringing and the fascinating, risky life he’s led. However, he feels uneasy about the honors he’s received, such as his 2017 knighthood. “I fI feel like I’ve been over-rewarded, and it definitely makes me uncomfortable because it came at the cost of other people’s lives. But I point out that he has witnessed atrocities, and that’s important. “Yes,” he says hesitantly, “but in the end, it hasn’t done any good at all. Look at Ukraine. Look at Gaza. I haven’t changed a single thing. I mean it. I feel like I’ve been profiting from other people’s pain for the last 60 years, and their suffering hasn’t helped prevent these tragedies. We’ve learned nothing.” It fills him with despair.

While McCullin’s most distressing photographs are his most famous, his 67-year career covers many genres, including beautiful landscapes, portraits, and images of ancient ruins and artifacts. On a recent late autumn day, we sat at his table in a lovely room filled with bookshelves, overlooking land where he has planted many trees, and he walked me through his life in pictures.

Guvnors, Finsbury Park gang, 1958

McCullin grew up in north London in a damp, two-room basement in a tenement building. His father had chronic asthma and died when McCullin was 14, after which he left school. He then did national service with the RAF, where he discovered photography. This photo of a gang of young men he grew up with was published in the Observer when he was 23 and working at a London animation studio, launching his career.

In Finsbury Park, people’s doors were always open. My mother was never home because she worked on the railway. We had gaslight, and there were many horses around, delivering coal or for the brewery. Sometimes, they’d let you sit on one. I come from a different culture.

During the war, I was evacuated three times, and each time I returned to a more derelict London. We would climb these bombed-out buildings. It was like climbing inside cathedrals, the skeletons of these structures, and we’d sit at the top eating chips in a roll. In a way, I had a real childhood. Sometimes, we’d take the train to Cockfosters, run across the live rails into the countryside, and catch grass snakes and birds’ eggs. Children don’t have lives like that today.

I used to get beaten up by bullies. I’d win the occasional fight but lose many others. These boys in the photo only talked about violence, robbery, and breaking into houses. One of them was an armed robber who had been in prison.

I was surrounded by violence and bigotry, and it was getting to me. These people hadn’t traveled like I had. I’d been to Sudan, Egypt, and Cyprus with the RAF and started developing my own mind.

But my background of no education, bigotry, and all that awfulness makes me feel like an impostor. Despite all I’ve learned, I still feel uncomfortable.

Near Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin, 1961

By the early 1960s, McCullin was freelancing for the Observer and other newspapers and magazines. He and his first wife, Christine, were still living in a two-room flat in Finsbury Park—one room served as the bathroom, kitchen, and his darkroom combined.

I was sitting in a cafe with my wife in Paris on a belated honeymoon. I saw a man reading Le Figaro with a picture of an East German soldier holding a Kalashnikov. I said to her, “When we go back, would you mind if I went to Berlin?” We’d only been married a few months. I asked the Observer if they wanted pictures, and they said, “We’re not sending you. It’s up to you if you go or not.” I went with the same camera I used to photograph the Finsbury Park gang—a Rolleicord I bought after finishing my national service. It was hard to compose pictures with it because of the square format. I had pawned it once for five pounds, and the one decent thing my mother did was to get that camera back. I saw other internationalAs other photographers arrived, decked out in the newest cameras, I felt shabby in comparison.

Protest during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Whitehall, 1962

This man tried to run from Trafalgar Square, but they quickly blocked his path to Whitehall. In the early ’60s, while working for the Observer, I photographed many political demonstrations and loved it. Some days there were brawls, which I could capture through my lens. This particular photo amuses me—despite everything, I can still find laughter within myself. I have a strong sense of humor.

Cyprus Civil War, Limassol, 1964

During my first war assignment, I was caught in a gunfight as Greeks surrounded the Turkish quarter of Limassol. Turkish civilians had taken refuge in public buildings like cinemas, where I took this picture of a Turkish gunman.

I had a contract with the Observer for two days a week, earning 15 guineas, when the editor asked if I’d cover the civil war in Cyprus. I felt like I was floating on air. On my first day in Limassol, I captured this image near a cinema—it looks like a Hollywood still, with the man dressed almost too well. When the fighting stopped at night, I had nowhere to stay, so Turkish police let me sleep in a cell block. That was my introduction to war.

Another day, as I walked toward a village, a British soldier warned me about a dead body ahead. I kept my eyes on the ground, afraid to look up, until I came across the first corpse. I knocked on a house door, but no one answered. Gently opening it, I was hit by the warm smell of blood covering the floor. Inside, two brothers lay dead, and their father was murdered in the kitchen by Greeks. While I was photographing, the door opened and several people entered, including a woman weeping for her husband, whom she had married just weeks earlier. I feared they might attack me, but instead, they were remarkably kind.

I felt I had chosen the right path because the injustice I witnessed made me eager to return to England and publish my photos, exposing the world to these wrongs. When you’re young and ambitious, you don’t fully grasp it all. You’re drawn to tragedy, yet it isn’t yours—you’re intruding, unwelcome and uninvited, in a way stealing others’ emotional pain and images of the dead without their consent. I knew it wasn’t entirely right, and I still believe that today. That’s why I now focus on English landscapes—to try and free myself from the guilt I still carry.

Suspected Lumumbist Freedom Fighters Being Tortured, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1964

The German magazine Quick sent me to cover events in the DRC, where followers of assassinated Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba had seized the eastern region. Arriving in what was then Léopoldville (now Kinshasa), I found that journalists were barred from leaving. In my hotel bar, I met a mercenary hired by the government to fight rebels and convinced him to lend me a uniform and get me on a military flight to the rebel stronghold, Stanleyville (now Kisangani).

Early in the morning on the runway, as names were called before boarding, I worried they’d discover I wasn’t a mercenary. When asked my name, I said “McCullin,” and he just told me to get on the plane. I flew 1,000 km to where military leader Joseph-Désiré Mobutu was based.I was told no press were allowed to go. When I reached the other side, I saw the loyalist gendarmerie torturing boys as young as 17, maybe even younger. They were shooting them in the back of the head and kicking their bodies into the river. These boys were Lumumbists. They were being beaten; one had been stabbed in the face with a knife.

That happened on the Caledonian Road, where there used to be large slaughterhouses on both sides. I was working on a magazine story with the writer Eric Newby, who has long since passed away. So many people I worked with have died that I feel like one of the few left who remember the world I was part of.

I first went to cover the Vietnam War in 1965 and returned several times. I joined a group of US Marines who said the operation in the ancient city of Hue would last 24 hours. Twelve days later, we were still there—they suffered heavy losses. They lost about 40 men, with a sniper picking them off daily. You can see the destruction in this photo. I slept on the floor of a hut, under a table, using my helmet as a pillow. I loved being pushed to my limits. Every morning, I left the hut the same way, but one day I decided to go a different route. Behind the hut, I found a dead North Vietnamese soldier who had been lying almost head-to-head with me. He was about 18, his eyes open and filled with rainwater.

I’m a bit tired of my more famous pictures because they’re so perfectly composed. What do they really say? They might even come across as negative because they’re too carefully designed by me, and people might say, “It’s almost artistic.” I’m afraid of crossing that fine line.

I never harmed anyone in my photos. I didn’t kill or torture them, unlike the man who was tortured by his own breakdown. Every night, I remember the battle that man was in. I didn’t suffer his brain injury, but my mind has never been free from certain images. I have bad dreams and a moment of hesitation each night before I sleep, but I’ve never had post-traumatic stress disorder.

I was always on the move, ready to go straight to another war. There’s an adrenaline rush. It’s selfish and foolish, but you’re not being honest if you say you didn’t find some aspects exciting—like the thrill of incoming shells. But then you think, “That shell just blew someone’s leg off,” or killed four or five others. I’ve been caught in a whirlpool of terrible misadventures, and my life has been a cesspit, really. There’s no other way to describe it.

I’ve risked my life a few times. Once in Cyprus, during a gun battle, I saw an old woman who couldn’t walk. I thought if no one helped her, she’d be dead in five minutes. I handed my cameras to a friend, ran to pick her up, and carried her back. I thought, “I can’t just keep taking; I have to give something back.” In Vietnam, I carried a wounded soldier away from the battle on my shoulders. He’d been shot and was in agony. I thought, “I’ve been stealing all these years; I need to repay some of that.” But doing so puts your life at risk.

The day after my third child was born, I left to cover the war that broke out when Biafra seceded from Nigeria in 1967. After witnessing battles, executions, and other horrors, and then contracting malaria, I was about to see what would haunt me the most: a hospital for war orphans where hundreds were starving.

This is possibly the most horrific picture I’ve ever taken. There were 600 children dying in that camp. They were…Watching people starve and die right before my eyes was devastating. When they see a white person, they assume you’re an aid worker bringing food. So you can understand the guilt I felt, can’t you? My presence there felt unkind, truly.

One boy was holding an empty tin of corned beef that he had licked clean to get every last bit. I gave him a barley sugar sweet from my pocket, and he walked away, licking it. Later, while I was talking to a Médecins Sans Frontières doctor, I felt someone take my hand. It was that boy again. It made me feel incredibly guilty.

I haven’t printed that photo for almost 30 years. I don’t want to see it appear in the darkroom. I even feel guilty that these images—I have around 70,000 negatives—are stored in my house.

In London, 1969, I encountered a homeless Irish man. Social conflicts are right on your doorstep. People used to write to me saying, “I want to be a war photographer.” I’d tell them, “Look around—it’s happening in your own cities.” This man slept by a fire in Spitalfields market, very close to the City of London, which generates immense wealth for its owners. The contrast couldn’t be starker: one side has everything, the other has nothing.

I call this picture Neptune because he resembles the sea god. I thought he was one of the most handsome men I’d ever seen.

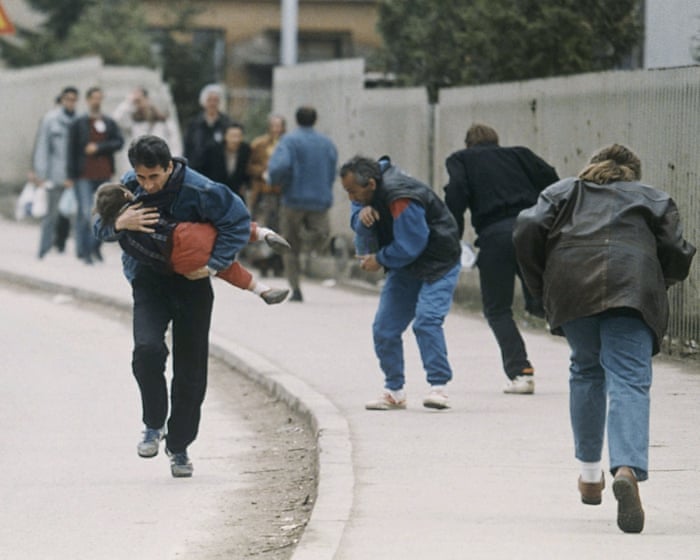

In Londonderry, 1971, I captured Catholic youths escaping CS gas fired by British soldiers. During the late 1960s, I was rarely home. I covered wars in Chad and visited rebel camps in Eritrea. Even after being injured in Cambodia—watching a man die from a mortar blast on the way to the hospital—I returned months later. I documented tribes in the Amazon rainforest whose lands were being seized and the refugee crisis in Pakistan. On that trip, I realized I was more interested in showing how violence affects civilians, which I could do in Northern Ireland.

I spent six weeks there during the gassing in the Bogside area. That day, I was badly gassed and hit in the back with a rubber bullet. I was led away, completely blind, into a house filled with chaos, swearing, and shouts of “Get him a damp cloth!”

In another photo from Londonderry, 1971, a man is coming home from work while a soldier acts as a soldier. It highlights the stark contrast between an ordinary person’s daily life and the military presence on the streets.

In Bradford, 1972, I took a photo of local boys. After returning from war zones, I’d often set myself projects, frequently in northern England, drawn to documenting people’s hardships in industrial decline. I used to walk the streets, and people in the north were very friendly and trusting. In Bradford, I saw that powerful anti-racism slogan on the wall. I’m proud of my work there. As a child, I was evacuated to a chicken farm in Lancashire for 18 weeks and had a terrible time, which is why I treat others with respect.

If I had gone to university, I think I would have been even more sensitive and unable to sleep among dead bodies or in rat-infested trenches. But I knew how to handle myself. You can smell poverty in a house—it reminds me of the home I grew up in.

In an undated photo from Hertfordshire, titled “A winter’s victim,” I captured another aspect of hardship. In 1972, I was captured in Uganda and was certain I would die in the notorious Makindye prison, listening to the sounds of…He saw fellow prisoners being taken away to be beaten or executed, and watched trucks carrying bodies off. After four days, he was released and deported, returning home to his family—now living in a farmhouse in Hertfordshire.

One evening at dusk, I found this sparrow outside my house. I have sharp eyes and tend to notice things on the ground everywhere. It’s like I have X-ray vision.

Young Christians in Beirut, 1976, celebrating the death of a Palestinian girl.

Having visited Lebanon several times in the 1960s, when Beirut was a decadent playground for the wealthy, McCullin returned in the mid-1970s to cover the civil war. Upon arriving, he decided that embedding with the Christian Phalange militia would give him the best access. Over the following days, he documented massacres in an east Beirut district largely inhabited by Palestinians—an act that would later put his name on a death list.

One morning, he was told, “We’re going to Karantina to clear out the rats,” referring to the Palestinians. He spent that night in a morgue, and early the next morning, the militia attacked the area.

The Christians warned him to leave, saying, “If we see you taking any more photos, we’ll kill you.” He had witnessed them killing Palestinians in groups, firing entire magazines into men’s heads. As he was leaving, he heard strange music and saw a dead Palestinian girl lying in the rain. A boy nearby had found a mandolin in one of the houses. Though he couldn’t play it, he gave the impression of serenading the girl’s death. McCullin quickly took the photo, aware of the risk.

Dew pond, Somerset, 1988.

By the mid-1980s, McCullin’s style of work had fallen out of favor at the Sunday Times, which had been acquired by Rupert Murdoch, so he left. It was also a difficult period personally—he had been injured in El Salvador after falling off a roof during a gunfight, and he left his first wife for the woman who would become his second, something he still feels guilty about. (He has been married to his third wife, Catherine, a writer and podcaster, for over 20 years.) Money was tight, and he turned to advertising photography, though it didn’t fulfill him. Moving to Somerset brought him peace, and he began photographing the landscape around his new home.

Dew ponds are rare, almost mythical. They are perfectly round, and this one lay at the foot of a hill fort. Somerset is rich with history and myth, which inspires his work. This photo was taken early in the morning, though he usually works in the evening as the sun sets.

He can spend two or three hours in the fields without taking a single photo, but he doesn’t feel disappointed. He considers it a privilege just to be there—there’s nothing greater.

Photojournalism has declined, he believes, because newspaper owners prefer images of beautiful women, rich people, and celebrities. They don’t want his kind of pictures in their papers, spoiling their readers’ day with tragedy.

Tulips with a mind of their own, undated.

He observes things closely. Tulips start out pristine, but eventually they begin to dance in different directions. Photographing them is a free and joyful experience. They can’t tell him, “Don’t photograph us in our decline.”

The road to the Somme, France, 1999.

He was commissioned by Royal Mail to create a commemorative stamp for the First World War. One day, after lunch in a French bistro during the rain, he was driving back when he suddenly saw this silvery wet road and turned his car around. He felt that the horizon represented the vast graveyard of thousands of young men who didn’t want to die—many not even 18, having never truly lived.

Refugee camp, Chad, 2007.

He w…I was sent by Oxfam to photograph refugee camps in Chad, where people were fleeing violence in Darfur. In my experience, I’ve seen TV crews come in and act as if they’re more important—stepping on children and pushing people around. Growing up in Finsbury Park made me tough, so I’ve always stood up to such behavior. But in my work, I’m sensitive and polite because I’m a human being. Without that approach, I wouldn’t have been able to capture images of injured, angry, and hurt individuals, or earned their trust in those moments. If I didn’t think this way, my photos wouldn’t convey a sensitive message to you.

The exhibition “Don McCullin: A Desecrated Serenity” is at Hauser & Wirth in New York until November 8. McCullin’s new book of still lifes and landscapes, “The Stillness of Life,” is published by Gost Books and costs £80. All photographs are copyright Don McCullin. The photos discussed by Saner and McCullin were selected by picture editor Sarah Gilbert.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about the topic My life has truly been a cesspit war photographer Don McCullin reflects on his most powerful images

General Beginner Questions

1 Who is Don McCullin

Don McCullin is a renowned British photojournalist famous for his powerful blackandwhite photographs taken in war zones and areas of conflict around the world

2 What does the phrase my life has truly been a cesspit mean in this context

He is using it as a metaphor to describe how his career forced him to repeatedly witness and immerse himself in the absolute worst of human suffering death and depravity which has left a deep and traumatic mark on his soul

3 What kind of images is this article or exhibit about

It focuses on 19 of his most iconic and harrowing photographs from conflicts in places like Vietnam Cambodia Biafra and Lebanon as well as his photos of poverty in England

4 Why is his work so important

His work is important because it doesnt glorify war it exposes its brutal reality He brought the true human cost of conflict into the living rooms of people who were otherwise detached from it serving as an unflinching historical record

Deeper Advanced Questions

5 What is the main message or theme of his reflections

The main theme is the profound moral and psychological burden of witnessing atrocity He reflects on the conflict between his duty to document the truth and the personal trauma he accumulated questioning whether his photographs ever truly made a difference

6 How did his experiences affect him personally

He has spoken extensively about suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder depression and guilt for decades He carried the emotional weight of the scenes he photographed for his entire life

7 What is the significance of him shooting in black and white

Black and white removes the distraction of color forcing the viewer to focus solely on the raw emotion composition and stark reality of the subject matterthe light shadow and human expression It adds a timeless grave and artistic quality to the documentation

8 Did he just photograph wars abroad

No a significant part of his work documented social issues in postwar Britain capturing poverty and hardship in industrial cities like Londons East End and the North of England This showed that suffering existed close to