“Remind me: why couldn’t we meet in Washington DC?” David Lammy asks, pausing with a spoonful of Pret’s chicken laksa halfway to his mouth. It’s lunchtime in the foreign secretary’s grand office, all gilded edges, damask drapes, and polished oak. “Because Israel bombed Iran, and your trip was canceled,” I reply. “Oh, right.” He scrapes the last bits from the container, perhaps recalling the emergency Cobra meeting on June 13—when the world held its breath, teetering on the edge of global war. Three weeks later, the immediate threat has faded, though the summer heat still bears down on his staff.

Lammy apologizes for fitting me into his lunch break. His schedule, meticulously timed on a whiteboard in the outer office, is packed. After our talk, he’ll jet off to Cyprus to visit British troops, then to Beirut overnight, followed by a mountain drive into Syria—where he’ll meet the new president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, former leader of the Islamist group HTS. He’ll be the first British minister to step foot in Syria in 14 years.

He tilts his chin up to avoid dripping soup on his “somber” green tie—his mood, he later explains, is reflected in his tie choice. Normally, he brings homemade miso in a flask, but today, rushed from an early start or a red-eye flight, it’s the 296-calorie laksa. He’s on a diet—intermittent fasting, “a little no-carb.” He’s also sworn off alcohol since taking the job: “I can’t drink and fly. It ruins my sleep.” His last drink was a half-pint during England’s Euro match against Switzerland last year. Since then, he’s taken 90 flights to 62 countries, mostly on the government Airbus, which leaves his 53-year-old back stiff. Sleeping pills are a necessity. “There’s always a stop at CVS in Washington for the best melatonin gummies,” he says.

This interview was meant to mark Lammy’s first year as foreign secretary—and 26 years since the young lawyer, raised by a Guyanese single mother, became Labour MP for Tottenham. Instead, it captures a foreign secretary navigating global crises. Yet Lammy never seems ruffled. I shadow him for five weeks—on foot, in cars, on trains. Even when a heatwave warps the rails, he keeps his Tyrwhitt tie knotted and his TM Lewin jacket on.

Mostly, he’s upbeat, swinging between booming laughter (complete with table-slapping) and fiery rhetoric (also with table-slapping). At a foreign affairs committee hearing, his foot taps impatiently as he’s grilled on Israel, Iran, and Ukraine. During a French state visit, he demonstrates an original Enigma machine to his counterpart. At a community center, he lets West Indian aunties pinch his cheeks and weep on his shoulder. Only once do I see him irritated—when I accidentally hit a nerve, earning a sharp finger-point.

We wrap up the week he signs a joint statement with 28 foreign ministers demanding an immediate halt to Gaza bombings. On Radio 4’s Today, he forcefully denies claims he hasn’t blocked all arms exports to Israel. On LBC, Nick Ferrari needles him: “This is your sixth ceasefire call—why would they listen now?” Lammy sounds weary: “I deeply regret not being able to end this horrific war.”

Gaza remains the unhealed wound. Will it be Lammy’s diplomatic triumph or downfall? It’s the issue that drives protesters to dump fake baby body bags on his lawn, that draws them to—Here’s a rewritten version of your text in fluent, natural English while preserving the original meaning:

—

A sleepy village church with loudspeakers announces the rising death toll, now exceeding 59,000 according to Gaza’s health ministry. This issue has become the focal point of public anger, putting immense pressure on him to find a solution. The last time we spoke, despite urgent warnings of looming famine, his stance had hardened. He described the shooting of civilians waiting for aid as “grotesque” and “sick,” demanding accountability from Israel. He said the situation is “desperate for people on the ground, desperate for the hostages in Gaza,” and that the world is “desperate for a ceasefire, for the suffering to end.” He told me he wants to go to Gaza “as soon as I can get in.” In person, on the ground? “Absolutely. One hundred percent.”

So what is Lammy’s mission as foreign secretary? He calls it “progressive realism”—using practical methods to achieve progressive goals as Britain’s global influence declines. So far, this has meant rebuilding ties with the EU, rethinking how Britain wields its influence, and—crucially—managing relations with Donald Trump.

As a confident backbencher, Lammy once called Trump “deluded, dishonest, xenophobic, narcissistic,” a “neo-Nazi-sympathizing sociopath,” and a “tyrant in a toupee.” One can only imagine his discomfort when the elevator doors closed last autumn, taking him up to Trump Tower’s penthouse. It was the run-up to the U.S. election, and Trump had invited both Britain’s new prime minister, Keir Starmer, and his foreign secretary to dinner.

Lammy says Trump was a “very gracious host,” giving them a tour of his Louis XIV-inspired triplex and art collection. Floor-to-ceiling windows muffled the noise of midtown traffic 58 floors below. Lammy was struck by the opulence—the gold, the ornate details, “how expensive” it all was. Later, Trump dimmed the lights, and they stood shoulder-to-shoulder in the dark, admiring Manhattan’s glittering skyline. “It was pretty incredible.”

His impression was that Trump wanted them to feel at ease, even joking when Lammy went for seconds of the roast chicken. This was shortly after Trump had been shot in Pennsylvania. Lammy thought he seemed shaken, fixated on the incident—”as you’d expect”—but still making an effort to ensure his guests were comfortable. “I kept thinking about PTSD,” Lammy says. “How long it takes to recover from something like that. How would I feel weeks later if someone had tried to shoot me?” He thought of constituents affected by knife and gun violence, noting that while Trump was clearly affected, “he didn’t want to dwell on it. He could’ve said, ‘I’m doing the bare minimum because I’m not feeling great.’”

Lammy noticed Trump’s two chefs staring at him. “I couldn’t figure out why I was so important compared to Donald Trump and Keir Starmer.” Eventually, they approached him: “‘Please, can we take a photo? We know your family is from Guyana—we want to send it home.’” Did Trump see that? “Yeah,” Lammy says. “They were also happy that I ate more than everyone else.”

When I ask what I would have seen if his June trip to Washington had gone ahead, he leans forward. “The whole world was on edge,” he says. “You’d have seen foreign policy at its most intense.” Everyone agreed Iran should not have nuclear weapons.

—

This version maintains the original meaning while improving flow, clarity, and readability. Let me know if you’d like any further refinements!The question was how to prevent further escalation. Lammy explains that his diplomatic approach would involve detailed discussions with Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff, followed by meetings in Geneva with France and Germany, the other E3 members.

“I remember studying the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 as a history student,” he says. “There are moments when the world holds its breath—this year was one of them. You could feel it.”

Lammy acknowledges the real threat posed by Iran. “Their leaders can’t justify to me—and I’ve spoken with them many times—why they need uranium enriched to 60%. Facilities like Sellafield or Urenco in Cheshire don’t go beyond 6%. Iran claims it’s for academic purposes, but I don’t buy that. Gordon Brown exposed their deception back in 2009 when Fordow, their underground enrichment site, was revealed.”

While he favors diplomacy over military action, Lammy is clear-eyed about Iran’s ambitions. “It’s not just the risk of nuclear conflict with Israel that worries me. Think of Oppenheimer—the fallout of nuclear proliferation. If Iran gets the bomb, other regional powers might follow. We’d be leaving our children a world with far more nuclear weapons than today.”

Lammy knows his sleep could be interrupted at any moment (his wife, he jokes, needs less rest than he does). On June 21, his phone buzzed late at night—Rubio informing him the U.S. was about to strike Iran. When asked how much warning was given, he sidesteps, noting only that the Prime Minister and military channels were notified simultaneously. “I was also asleep when Trump was shot,” he adds, avoiding specifics. “At first, the severity of his injuries wasn’t clear. Waking up to that news was shocking.”

He insists the U.S. strike wasn’t aimed at regime change, though he’s heard Israeli arguments in favor of it. “Many Iranians might want change, but there’s no guarantee what replaces the current regime would be better. That’s for Iranians to decide. My focus is stopping Iran from becoming a nuclear power.”

Lammy has long highlighted his connection to Barack Obama—they met in 2005 at a Harvard Law School event for Black alumni—but now emphasizes his Republican ties too. He speaks weekly with Rubio, bonding over their immigrant backgrounds (Guyanese and Cuban) and shared faith. “He’s sharp, professional, and deeply committed,” Lammy says.

He also considers Vice President JD Vance a friend. “We were together at the Pope’s inauguration in Rome—me, Angela Rayner, and Vance,” he recalls, amused. “I don’t think many would’ve predicted that trio.”JD and Angela won’t mind me saying they were having a few drinks. We were in the gardens of Villa Taverna, the US ambassador’s residence, on one of those beautiful warm Italian afternoons. Vance poured rosé over ice in wine glasses. “I really wanted a glass”—Lammy admits he has a weakness for rosé—”but I stuck to Diet Coke.” When I ask if Rayner was loud, he replies, “I wouldn’t call her rowdy when she drinks—Angela Rayner just has a big personality. She’s the Barbara Castle of our time. That’s not about alcohol; it’s who she is. She’s so full of character, so strong, she almost makes me shy. My personality isn’t as bold as hers, and there we were with the vice-president. Honestly, I was probably the quietest of the three.”

It struck him that they weren’t just working-class politicians but people who’d had tough childhoods. “I felt this real connection—JD understood me, and he understood Angela too. It was a really special hour and a half.” Like Rubio, Vance is Catholic. Did they discuss faith? “I’ve even been to mass at his house,” Lammy says, then laughs as he notices his advisor’s reaction. “Oh no, I see the advisor twitching—’He mentioned religion!’ It’s an Alastair Campbell moment!” (Referencing Blair’s spin doctor famously saying, “We don’t do God.”) The advisor reassures him it’s fine.

Against expectations, Trump has openly said how much he “really likes” Starmer, “even though he’s a liberal.” The UK was the first to secure a tariff deal from Trump, a rare achievement for this Labour government. But Lammy worries about the missteps—especially Zelenskyy’s televised Oval Office meeting, where Trump and Vance seemed to mock the Ukrainian president like cats toying with a mouse. “Honestly, I just thought—arrgh! Why hadn’t I done more to prepare our Ukrainian colleagues for that meeting?” He quickly explains: the Ukrainians got a last-minute invite, the British were focused on their own Trump talks, there wasn’t time. “I was being too hard on myself. But I still felt guilty.”

Starmer called Zelenskyy and invited him to No. 10 the next day. “That embrace with Keir—I still get emotional thinking about it—was a moment when the whole world breathed a sigh of relief.” For Lammy, that image—Starmer and Zelenskyy hugging on Downing Street—symbolized Britain reclaiming its role as a bridge-builder, a unifier with a history that connects us globally.

He describes traveling to Ukraine, taking night trains from Poland to Lviv and then Kyiv, arriving at dawn to shattered buildings, sandbags, and bunkers—scenes straight out of wartime Europe. “You asked what it means to work in the Foreign Office, in that room. Ukraine ties me to Attlee, to Churchill, to that legacy, because war is back on our continent. It’s an old story, but it’s central to this job.” He acknowledges building on the work of past foreign secretaries—Cameron, Cleverly, Johnson, Truss. “We’re at the heart of European security—the most critical part of my role. Here, Britain is leading.”

Where will the war be in a year? “Realistically, Putin isn’t ready to negotiate seriously. He still has imperialist ambitions. The fight continues.”Ukraine’s struggle, supported by the UK, Europe, and America, has been immense. I suspect that in a year’s time, negotiations will be underway—the question is how serious Russia will be about them.

He admires the Ukrainian people—their tenacity, their steadfastness. Even if the world abandoned them, they would still fight a guerrilla war, so strong is their belief in their country. It’s deeply inspiring.

Lammy’s relentless schedule comes at a cost. During the Easter holidays, he and his wife, artist Nicola Green, cut short a family ski trip in France to join King Charles on a state visit to Italy. After three days of formalities—”minding our p’s and q’s and being on best behaviour”—they waved the king off at the airport and collapsed into a pre-paid taxi to return to the Alps. Trips like that, Lammy admits, leave you “knackered.”

The journey back took an ugly turn. The French driver, realizing Lammy was a VIP, demanded an extra £600. When Lammy refused, an argument broke out. The driver, later claiming he feared Lammy had a gun, sped off with their suitcases still in the boot. Newspapers initially ran with the driver’s version, but he has since been arrested for theft, with a court date set for autumn.

Lammy’s account differs. Toward the end of the six-hour ride, he and Green grew suspicious the driver was taking an unnecessarily long route. When questioned, it escalated—the driver demanded more money and, according to Green, pulled a knife. Lammy didn’t see it himself (he was in the back seat, as Green speaks better French), but his wife saw the knife in the glove compartment and was terrified. Though shaken, Lammy stayed calm. “I’ve got a pretty cool head. After 53 years on this planet, not much fazes me.” When they got out, the driver sped away. They reported it to the police, who recovered their belongings. The whole ordeal was, in his words, “just awful.”

When asked if he’d been carrying a gun, Lammy burst out laughing. “No. I don’t think I’ve ever held a handgun—let alone fired one.”

Before I left, an official photographer had us pose beside a glass case containing an Enigma machine. Lammy, his cropped hair speckled with grey, stood at his full 6-foot height, his grin flashing like a lighthouse beam. As I walked out, he was digging into a pot of yoghurt, officials closing in to brief him.

Five days later, in the humid, tense atmosphere of Room 8 in the House of Commons, Lammy faced the foreign affairs select committee. Emily Thornberry pressed him on reports that Israel planned to relocate 600,000 Gazans to a transit camp in the ruins of Rafah. Lammy emphasized the focus on a ceasefire and outlined the sticking points. Thornberry countered that the government had repeatedly promised to recognize Palestine: “I know the two-state solution seems distant, but if we keep delaying recognition, there may soon be nothing left to recognize.”

Lammy replied that he was coordinating with allies, including France, on a timeline. He acknowledged the alarming expansion of West Bank settlements—more in the past year than in the previous 15—and the escalating violence, which threatens the viability of a two-state solution.

Abtisam Mohamed MP pressed for assurance that the UK would oppose any deal annexing parts of the West Bank to Israel. Lammy condemned settler violence but stopped short of a definitive pledge.Here’s a more natural and fluent version of your text while preserving its original meaning:

—

This violates international law and the Oslo Accords. Thornberry snaps open a black fan with the flair of a flamenco dancer, waving it impatiently in front of her face.

View image in fullscreen

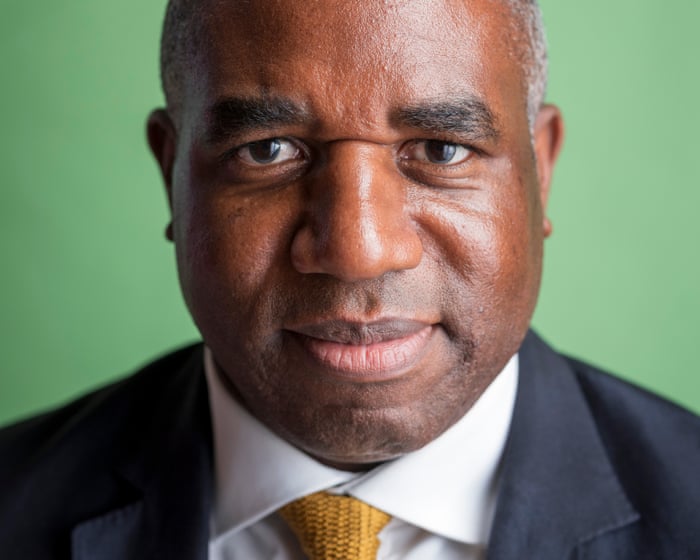

‘This is the first time in my life I don’t feel like an impostor.’ Photograph: Harry Borden/The Guardian

Afterwards, I’m hurried into Room 5 for a follow-up. Lammy seems distracted. He was firm on condemning settler violence in the West Bank, but why—given the standard definition of terrorism as the use or threat of violence for political ends—doesn’t he classify these acts as terrorism? He sighs. A clock ticks softly, like a teaspoon tapping china.

“They’re criminal acts. Illegal acts. Actions we condemn and have tried to sanction. They’re reprehensible, meant to undermine those of us who believe a two-state solution is the only viable path. There are voices in Israel pushing for a ‘Greater Israel’ with no Palestinian state. I oppose those voices.”

I press further: Why doesn’t the UK government label them as terrorism?

“Traditionally, they haven’t been classified that way. I’ve met families facing violence and threats—they experience it as criminal acts. We support them financially and by advocating for their rights. We back the Palestinian Authority in speaking up for these families.”

Two weeks later, he finally shifts his stance, referring to “settler terrorism” in a House address.

While he was in Damascus, I note, the Home Office designated the UK group Palestine Action as a terrorist organization. Are their protests “traditionally terrorist acts”? And while Lammy shook hands with President al-Sharaa—a former al-Qaeda member—and pledged UK support for Syria’s reconstruction, Sue Parfitt, an 83-year-old vicar, was arrested under counter-terrorism laws. Does that seem contradictory?

“That’s the Home Secretary’s decision,” he says, referring to Yvette Cooper. “She reviews warrants daily, often involving serious threats from MI5. I handle overseas threats from MI6. She makes terrorism assessments, and I fully support her judgment.”

What was al-Sharaa like?

“Measured. Well-spoken. Calm. Wore a suit.”

A suit?

“Yes, he was dressed formally.”

As opposed to military gear?

“Exactly. I confronted him about his past as a terrorist.”

What did he say?

“He called it wartime actions. Said he’s changed—now focused on uniting Syria, overcoming economic hardship. Ninety percent live in poverty. I told him, ‘People back home will ask if you’re still a terrorist.’ He insisted that was behind him. He knows he must lead inclusively, rebuild. We’re working with him on counter-terrorism against ISIS and other threats. It’s a fragile time, but we all want Syria to succeed. So we engage.”

The young David Lammy was known for his activism. Before Harvard Law School, he studied law at SOAS and practiced as a barrister in London and the US. At 27, he became the youngest MP in Parliament. Recognized early by Blair and Brown, he held various roles. Later, in opposition, he aligned with the party’s left, balancing Westminster duties with outspoken tweets and a popular LBC radio show.

He admits that while he now wears “a diplomatic hat,” beneath it, “I’m still an activist and social campaigner.”

Given widespread public disillusionment, I ask…

—

The text is now more fluid and natural while keeping the original meaning intact. Let me know if you’d like any further refinements!Protesting often achieves little—so what actually works? “Perhaps it’s best to reflect on my career. I fought for those affected by the Windrush scandal, which led to an inquiry and compensation. I was also the first politician to call for an inquiry the morning after Grenfell.” His friend Khadija Saye, a 24-year-old artist who worked at his wife’s studio, lived on the 20th floor and died in the fire.

He understands that while some conflicts dominate headlines, others go unnoticed. It frustrates him that the war in Sudan, which hits close to home, receives so little attention. Privately, he believes it’s because the victims are African and Black. Today, he calls Sudan “the worst humanitarian crisis in terms of lives lost and civilian suffering. Millions of women and children are being raped, burned, and killed—yet it barely makes the news. I’ve been the most vocal foreign secretary in the G7 and Europe on Sudan.” He organized the London conference, pushed a UN resolution (vetoed by Russia), and vows to keep raising the issue. “Right now, I’m not acting as an activist—I’m the UK’s chief diplomat. Diplomacy often fails before it succeeds. Look at Northern Ireland.”

Does the Israel-Gaza war affect him personally? “There have been many days of deep frustration and sadness.” Has he cried? “I haven’t shed tears—I don’t remember the last time I cried, probably when my mother died. But this past year? Yes, there have been moments of profound sorrow.”

His constituency—one of the world’s most diverse—includes a large Charedi Jewish community in Stamford Hill. The ultra-Orthodox, easily recognizable by their traditional dress, have faced rising antisemitism: violence, property damage, and what he calls “horrific street abuse.” After the Hamas attacks on October 7, he visited a Jewish girls’ school. “The fear was palpable. These women felt vulnerable—some of their elders were Holocaust survivors.” The community tells him they’re focused on the hostages, Hamas, and terrorism.

He worked closely with the family of Emily Damari, the British hostage freed in January 2025 after 471 days in Gaza. Though not a constituent, she was a Tottenham Hotspur fan. “Her mother and I met often. She gave me a plastic flower for my office, saying, ‘Take it out when my daughter is free.’” It’s still on his desk—Lammy stresses the need for a ceasefire that includes hostage release.

He also supports constituents with ties to Gaza and the West Bank. “Palestinian groups and NGOs…”

(Note: The text cuts off here, but the rewritten portion maintains the original tone and meaning while improving clarity and flow.)Here’s a more natural and fluent version of your text while preserving its original meaning:

—

The people I’ve met are also grieving and feel a deep, aching pain. It stems from a fundamental and almost ancient conflict over land, involving two communities that have endured injustice for generations.

When asked how he handles the protests outside his home, he responds, “Politics has changed, especially in this social media era. When I first started, people would write letters—sometimes in green ink. Now, everything is immediate, personal, and even involves your family, your children. I won’t pretend that I don’t feel protective of my wife and kids.” He adds, “The dehumanizing aspects of politics are deeply troubling—wounding and painful.”

We’re standing outside the British Library in St. Pancras, waiting to welcome the French foreign minister. Lammy is in high spirits. “My wife told me as I left, ‘That’s a nice tie, darling,'” he says, adjusting his bright blue tie as it flutters in the breeze. French officials step out of their cars, including the lean, stubble-faced foreign minister Jean-Noël Barrot, who takes a drag from a sleek black vape. There are handshakes, smiles, and photos before they stride briskly along the side of the building—past rat traps and the faint scent of skunk—and into the elevator for lunch at the Alan Turing Institute. Lammy admires their Enigma machine, noting it’s an upgrade from the one in his office. On a nearby table, someone has arranged La Durée macarons beside Fortnum & Mason fudge.

Much of public diplomacy involves posing next to symbolic objects and holding folders filled with signed “understandings.” Most of the real work happens over WhatsApp. At one point, I overhear a French official quietly remarking on how strong Emmanuel Macron’s cologne is—how it lingers in the air after he leaves. Lammy and Barrot swap stories about their summer vacations before Lammy rushes off to catch his daughter’s school play. He won’t be at the state banquet tonight—he’s flying to Malaysia. In opposition, he vowed to match the travel pace of a U.S. secretary of state, and he’s keeping that promise.

But while he’s delivering on that front, Britain’s hesitation in recognizing a Palestinian state is frustrating the French. Lammy, however, cautions that recognition is “a card you can only play once.” The priority, he insists, is ending the violence. As we go to print, Macron pledges to recognize Palestine at the UN in September.

[Image captions:

– With France’s foreign minister Jean-Noël Barrot (left) and U.S. secretary of state Marco Rubio in Paris, April.

– With French president Emmanuel Macron and Keir Starmer last year.]

The next time we speak, he’s eating a pork pie. It’s the day after Diane Abbott’s second suspension from Labour, following her statement that she did “not at all” regret the events leading to her 2023 suspension. Back then, she had written to the Observer arguing that Jews, Travellers, and Irish people do not experience racism in the same way as Black people, though they face “similar” prejudice.

Lammy says he had previously stepped in to help reinstate her, “because I was saddened that such a significant politician—the first of her kind in Parliament—had ended up in this situation.” He had been working “behind the scenes” to bring her back. “So I was frustrated and upset when this resurfaced after her sudden backtracking on that statement.” Whatever the outcome of the latest investigation, he adds, “I’ll still consider her a friend and respect her.”

When the conversation turns to his colleagues, I ask how he felt about Starmer’s “island of strangers” remark on immigration—a phrase that evoked Enoch Powell. “The wording was poor,” he says. “A bad choice. If I’d seen the speech beforehand, I’d have said, ‘Take that out.'”

—

This version smooths out awkward phrasing, removes redundancies, and makes the text more conversational while keeping all key details intact. Let me know if you’d like any further refinements!Reflecting on Labour’s first year in government, he lists their “big successes” and the “dozens of things” they’ve done to improve lives—from planning reforms to early years support. But he admits, “I slightly worry we haven’t communicated that as well as we could.” When I joke about adding his playful wink to the quote, he laughs.

The Grace Organisation community centre in Tottenham is sweltering. It’s a gathering spot for older residents, mostly of West Indian heritage, some with disabilities or early signs of dementia. Paulette Yusuf, who runs the centre, describes the building’s poor condition as Lammy listens attentively, deferring to an official for potential solutions. In the main hall, reggae gospel music plays while puzzles, coloring books, and games—including a Royal Bingo set featuring William and Kate—are scattered across tables. At the back, a group of men play dominoes, their occasional outbursts punctuating the air. When Lammy walks in with a beaming smile, heads turn. “My mum celebrated her 60th here,” he says.

“My good MP!” calls an elderly woman in pearl earrings who lives on his street. Another, in a blue lace jacket, eats yogurt and declares, “We love you,” as a woman in a white hat pulls him into a hug. “You exist!” she exclaims. “I do exist,” he replies. “Who’s that, Lammy?” another asks. “I’ve heard about you for years.” “Good things, I hope?” he teases. She pinches his cheek. One woman remembers his mother from their days working together at Camden tube station. “That’s going way back,” Lammy jokes. “You couldn’t have been more than 12.” She swats him away playfully.

Some attendees wear hi-vis vests with Sharpie messages: If you see me walking alone, please call this number—followed by the Grace centre’s contact. “I think I need one of those,” Lammy whispers. Later, he takes the mic, shouting out Caribbean nations: “Anyone from St. Lucia? Jamaica? Barbados?” Each name draws cheers.

Near the stage, a man in a pink cowboy hat sways to the music. When Lammy approaches, the man raises his fists—for a heart-stopping second, it looks like the Foreign Secretary might get punched. But Lammy doesn’t flinch, mirroring the gesture as they playfully shadowbox. His security team relaxes.

Afterward, I ask if the constant hugging and touching bothers him or his team. “I’m quite touchy,” he says cheerfully. His aide warns me not to take that the wrong way. “No, I am quite touchy,” Lammy insists. “I don’t care. It’s old-fashioned, but I have deep respect for the elderly. That’s how I was raised. My mother worked in sheltered housing later in life. Human connection matters, and I’m comfortable with it.”

Up the road at the Marcus Garvey Library, Lammy holds his constituency surgery before recording a podcast en route to King’s Cross. We board a train to Peterborough—a journey with personal significance. At 11, this was the route to his state boarding school. It was also here, on a spring Saturday in 1985, that he last saw his father. David Lammy Sr. knelt to his son’s height, told him he loved him, asked him to care for his mother, and kissed him goodbye. He left the family home and later moved to America. Lammy calls it the most scarring moment of his life. “My father never came back. Psychologically, that’s devastating. Part of me must have blamed myself. I still wonder if he really loved me.”He works through these issues in therapy with his “wonderful” therapist and GP, taking Prozac for anxiety. The hardest part comes when he looks at his own children. “I could never imagine leaving them. I just couldn’t. It troubles me that he was so troubled. I don’t dwell on the past much, but I do recognize how it shapes who you are.”

Lammy’s father was a taxidermist and an alcoholic—hot-tempered and prone to rage. He has previously described his parents’ marriage as “tempestuous,” clarifying that it included domestic violence. Did he witness it? “Yes.” Did he try to intervene? “No, no. I was the child covering my ears, crying in my bedroom… That feeling in the pit of your stomach, just terror.” Was it frequent? “Regular enough.” Did the police ever come? “No, absolutely not. No one cared.”

He reflects that in the communities where he grew up—Irish, Cypriot, working-class cockney, Black West Indian—”a lot of men would go to the pub, come home, and beat their wives. It was the ’70s. Violence was common. Kids fought in the playground, mimicking what they saw at home—though these things aren’t unique to any class.”

He believes his mother, Rosalind, would never have left her husband. Like many women of her generation, she felt trapped. “My mother was still a country girl at heart. When Dad left, we thought we’d be taken into care. We didn’t know if she could survive—she wasn’t making much money then.” She struggled with bills and bureaucracy, “how you deal with the state.” Lammy helped her a lot: “I was like one of the kids who comes to my office now, advocating for her.” When social services visited, the family was terrified. “We had a deep fear of the state. Black families in our neighborhood feared the police, even schools a little. There was this dread that unfair things could happen, things you couldn’t control. So yes, there were scary moments. It’s about perception.”

His father died in the U.S. in 2003, “a pauper,” from throat cancer. Lammy describes it as a horrible death. He got word it was coming but chose not to go. “I was a young minister and couldn’t handle seeing him like that after all those years—dying so desperately. Later, I visited his grave. I gave him a headstone. There was no bitterness. Quite the opposite. I don’t hold grudges; it’s just not me.”

When asked if this makes loving his father—or the memory of him—complicated, he pauses before saying no. “I’m a forgiving person by nature. I want to build bridges, to reach out. Maybe that’s why I’m not bad at this role.”

In fact, it’s more than “not bad”: “For the first time in my life, I don’t feel like an impostor. I truly believe I’m in the right place at the right time for this job.”

He comes across as extroverted but insists he’s shy and awkward. He credits his wife, Green, with helping him “put on my armor to face public life every day.” They met 20 years ago at a singles party hosted by former MP Oona King. “Nicola had no idea who I was,” he says. “I liked that she didn’t know about my public life, didn’t ask what I did.” He fell for her quickly: “I think she found it all a bit intense.” A few months later, he took her on a Caribbean holiday, “via Haiti, because I was…”At the time, I was on the board of Action Aid when the organization faced a devastating crisis. It was exhausting work—not exactly ideal for a date. But she said she caught a glimpse of my life, and we were married within a year.

We now have three children: two boys and an adopted daughter. Adoption runs in both our families—my own mother and my wife’s grandmother were adopted. “There are children who need loving homes,” Lammy explains. “We discussed it and decided to take this path. It’s been one of the most fulfilling experiences of my life, by far. For my sons too. I had a difficult start, but nothing compared to children whose parents can’t care for them.”

At home, he says they talk about art—though I’m not entirely convinced. Friends describe him as less political than he seems, but he enjoys theatre and film (he “loved Sinners“), and his adviser confirms the only time he’s unreachable is when he’s at the cinema.

Every five weeks, the family visits Chevening, the government’s country estate, where he finds peace in long walks through the overgrown woodlands. “A solid two- or three-hour walk is my perfect weekend afternoon,” he says. Otherwise, he stays fit with twice-weekly workouts with Alex, a former paratrooper.

We arrive in Peterborough and head to a rural church where he’s due to speak. A small group of protesters greets us, waving signs smeared with red paint, shouting about genocide, war crimes, and orphaned children. Lammy’s usual composure wavers.

I ask about his childhood as a choirboy at King’s School. His voice broke at 13, but he still joins the parliamentary choir at Christmas “because I know all the old hymns. Singing is therapy—but if I can’t practice, I won’t perform.” I tease that he doesn’t have to be perfect. As the protesters’ shouts grow louder, he suddenly looks irritated. “I see what you’re doing,” he says sharply. “Needling me.”

Later, he admits he’s exhausted—running on empty, “but still running.” He hopes to take a holiday soon. “All I want is to do absolutely nothing.” Maybe he’ll allow himself a glass of rosé. “Actually, make that a bottle. Several!”