By May 1985, Prince’s Purple Rain album had sold 11 million copies in the United States. One of those buyers was 11-year-old Karenna Gore. When her mother, Tipper Gore, heard the album’s fifth track, “Darling Nikki,” she was shocked by the explicit lyrics: “I knew a girl named Nikki / I guess you could say she was a sex fiend / I met her in a hotel lobby / masturbating with a magazine.”

“I couldn’t believe my ears,” Tipper Gore recalled. “The vulgar lyrics embarrassed both of us. At first, I was stunned—then I got mad!”

While parents being upset by their children’s music tastes was nothing new, Tipper was no ordinary Tennessee mother—she was married to Senator Al Gore, a rising Democrat politician. Determined to take action, Tipper reached out to Susan Baker, wife of James Baker, Treasury Secretary under Ronald Reagan, bridging the Democrat-Republican divide. Together with two other women, they co-founded the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC). Since all four women had husbands with strong government ties, the U.S. media nicknamed the group “the Washington wives.”

The PMRC organized a U.S. Senate hearing in September 1985, aiming to increase parental control over recorded music. Even before the hearings began, the PMRC had gained significant momentum. Funding came from Beach Boys vocalist Mike Love and Joseph Coors, owner of Coors Beer, both active Reagan supporters, and the committee received extensive media coverage, earning support from figures like Jerry Falwell, the televangelist and co-founder of the Moral Majority.

The campaign emerged at a favorable time. While the UK grappled with “video nasties,” Ronald Reagan’s emphasis on “family values” in the U.S. had empowered the religious right. With the rising popularity of MTV, musicians faced growing criticism from Christian organizations.

“Initially, I didn’t pay much attention to the PMRC,” said Blackie Lawless, leader of Wasp, one of the bands targeted. “Then it went on to have a huge impact and took on a life of its own.”

The U.S. had seen previous music-related moral panics. In the mid-1950s, segregationists condemned Elvis Presley for making “jungle music,” and John Lennon’s 1966 remark that “The Beatles are more popular than Jesus” led to bonfires of Beatles records. However, there had never been a coordinated government effort to censor music. As the Senate hearings began, it became clear that censorship was now on the table.

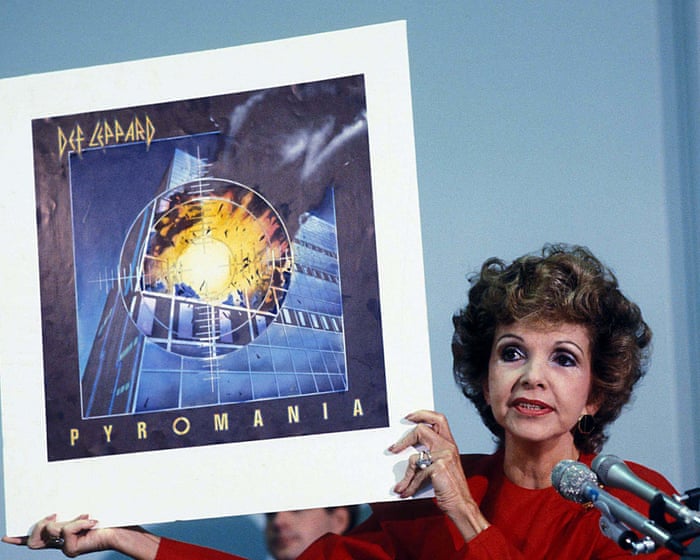

For the hearings, the PMRC compiled a list of 15 contemporary songs, dubbed the “Filthy Fifteen,” which they deemed objectionable due to themes like sex, violence, drug or alcohol references, occult themes, and profanity. Prince was associated with three of the songs as an artist, writer, or producer. The list also included Mary Jane Girls, Madonna, and Cyndi Lauper, cited for their subtly pro-female sexuality songs. Heavy metal bands, then the top-selling genre in the U.S., dominated the list. Veterans like AC/DC, Black Sabbath, and Mötley Crüe, who had previously faced attacks from evangelical groups, were included, along with newer acts like Def Leppard, Judas Priest, Twisted Sister, and Wasp. Suddenly, these artists found politicians and religious fundamentalists calling for their music and videos to be banned from radio and MTV.

“I had been following all of this building up on the news, so I wasn’t completely surprised,” said Judas Priest vocalist Rob Halford, “although being called ‘enemy of the people’ was a stretch.”During Senate hearings, the PMRC urged the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) to create a music rating system similar to the one used for movies. Their goals included placing warning labels on album covers, having record stores hide albums with explicit covers, pushing TV stations to avoid airing explicit music videos, and, more troublingly, reconsidering the contracts of musicians who performed in violent or sexual ways during concerts.

Alice Cooper noted that the Parental Advisory stickers likely had the opposite effect, making those albums more appealing to young people.

The PMRC’s campaign drew criticism not only from the musicians on their “Filthy Fifteen” list but also from seasoned artists like Frank Zappa and Alice Cooper, who had both faced controversy earlier in their careers. They saw the PMRC’s efforts as a guise for increasing censorship.

Cooper was no stranger to censorship battles, especially in the UK. In 1972, his band’s song “School’s Out” reached number one, sparking calls for it to be banned. He recalls sending flowers to conservative activist Mary Whitehouse and cigars to Welsh Labour MP Leo Abse, amused by their outrage.

Twelve years later, the PMRC campaign struck Cooper as more serious and sinister, an example of government overreach. He argued that it sent the message that children weren’t capable of handling certain content, insisting such discussions should be between parents and their kids, not the government.

As the Senate hearings began, Frank Zappa traveled to Washington D.C., joined by John Denver and Twisted Sister’s Dee Snider. All three testified against music censorship. Zappa, dressed formally, became a memorable figure as he debated the PMRC, calling their proposal poorly thought-out and a violation of civil liberties.

John Denver pointed out how his song “Rocky Mountain High” was mistakenly seen as promoting drugs when it was actually about appreciating nature. Dee Snider clarified that his band’s song “Under the Blade” was misunderstood—it referred to surgery, not sadomasochism as Tipper Gore had claimed.

Although Judas Priest’s Rob Halford wasn’t present at the hearings, he later stated that the PMRC also misread his lyrics. They alleged “Eat Me Alive” depicted forced oral sex, but Halford explained it was about consensual gay S&M. At the time, he remained silent, not publicly coming out until 1998.The Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

The Wasp song on the list, “Animal (Fuck Like a Beast),” was, according to Lawless, simply a straightforward celebration of passionate sex—not subtle, but not obscene either. He recalls, “Originally, I planned to attend the Senate hearings and testify, but EMI, our record label, asked us not to go. They didn’t think it was wise. Frank, John, and Dee all spoke well on behalf of artists, though it didn’t change much.”

Although the trio spoke eloquently, U.S. record labels gave in before the hearings concluded: the RIAA agreed to place Parental Advisory stickers on albums with “controversial” content. This led to some retailers, including Walmart—then the largest record seller in the U.S.—refusing to stock stickered albums. Halford notes, “At the time, the hard right pressured Walmart, leaving them no choice. I imagine every label’s sales suffered as a result.”

Lawless claims that the PMRC Senate hearings not only threatened his career but also his life. “There was a segment of society in the U.S. who believed, ‘The world would be better off without these people,’ and we started receiving death threats. I was shot at twice—thankfully not during a concert, though once while performing, someone threw a heavy glass jar that hit me on the head and split my scalp open.”

Musicians responded to the PMRC through their music: Judas Priest’s “Parental Guidance” and Alice Cooper’s “Freedom” both criticized the organization, while on Wasp’s “Live… In the Raw” album, Lawless dedicates the song “Harder, Faster” to the Washington wives, shouting, “They can suck me, suck me, eat me raw!”

The Senate hearings expanded the debate on censorship in the U.S. and sparked lawsuits against “offensive” musicians. San Francisco punk band Dead Kennedys faced a court case not for their music, but because of an insert of H.R. Giger’s artwork “Penis Landscape” inside their 1985 album “Frankenchrist.” A parent, upset by their teenage daughter buying the album, sued the band. On March 7, 1990, Dead Kennedys vocalist Jello Biafra debated Tipper Gore on the Oprah Winfrey Show, arguing that her defense as a “liberal Democrat” was contradicted by her support for the PMRC, which had energized the Christian right.

Both Cooper and Lawless suggest that Tipper’s motivation for the PMRC was to build support for her husband’s 1987 campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination. Al Gore ultimately lost the race but later became Bill Clinton’s vice president before controversially losing to George Bush in the 2000 election. Lawless states, “Just as McCarthy used the red scare to gain power, this was an effort to build a political base by claiming musicians were introducing sexual perversion and the occult into children’s bedrooms.”

Rap soon surpassed rock as the most popular youth music in the U.S., and gangsta rap lyrics drew even more outrage. In 1989, NWA and 2 Live Crew caused major controversy—NWA for lyrics that celebrated shooting LAPD officers, and 2 Live Crew for the explicit sexual content on their album “As Nasty As They Wanna Be.” After a federal judge ruled the album obscene—a first for a U.S. music recording—Bible belt states prosecuted stores selling the album and hosting their shows. The U.S. Court of Appeals later overturned the obscenity ruling, but by then, the controversy had helped both groups sell millions of albums, though numerous legal battles would eventually break them up.Both groups.

“I found the whole thing patronizing and stupid,” says Cooper. “And putting Parental Advisory stickers on albums surely backfired because they made those albums the ones kids wanted to buy.”

Although the PMRC officially disbanded in the mid-1990s, its legacy lives on through the Parental Advisory stickers still used on many US albums. In the internet age, where almost anything, no matter how offensive, is just a click away, the committee’s efforts to censor popular music now seem outdated. Yet, their crusade echoes today in attempts to censor comedians like Jimmy Kimmel for his remarks about the assassination of conservative activist Charlie Kirk.

“We are in dangerous times around the world,” says Halford. “I’ve lived long enough to see history repeat itself.”

Alice Cooper’s album The Revenge of Alice Cooper is now available from earMUSIC.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about the 1980s US Senate hearings that targeted rock music framed in a natural conversational tone

Beginner General Questions

1 What was I was branded a public enemy all about

This phrase captures how many 1980s rock and metal musicians felt after being targeted by the US Senate and a group called the Parents Music Resource Center They were accused of putting harmful content in their lyrics which they felt unfairly turned them into villains

2 Who was involved in this clash

On one side was the PMRC founded by the Washington Wives On the other side were famous musicians like Dee Snider Frank Zappa and John Denver who testified before a Senate committee

3 What was the PMRC and what did they want

The PMRC was a committee formed by parents who were concerned about explicit content in popular music They didnt want to ban music but they pushed for a voluntary rating system like the one for movies or warning labels on albums

4 What kind of songs were they complaining about

They pointed to songs with sexual themes occult references and general rebellion

5 What was the outcome of the hearings

The hearings didnt result in any laws but they led to a voluntary agreement with the Recording Industry Association of America This is why you started seeing the Parental Advisory Explicit Lyrics sticker on albums

Advanced Detailed Questions

6 Why did musicians like Frank Zappa and Dee Snider testify

They testified to defend artistic freedom and fight against censorship They argued that the PMRCs campaign was based on misunderstanding their music and that it was a parents jobnot the governmentsto monitor what their children listen to

7 Wasnt John Denver a cleancut artist Why was he there

John Denver testified to show that censorship could affect any artist not just heavy metal or rock acts He was concerned that a rating system could unfairly limit the distribution and radio play of his own music based on subjective judgments