This CSS code defines a custom font family called “Guardian Headline Full” with multiple font weights and styles. It includes light, regular, medium, and semibold weights, each in both normal and italic versions. For each style, the code specifies three different font file formats (woff2, woff, and ttf) hosted on the Guardian’s servers, ensuring broad browser compatibility.@font-face {

font-family: Guardian Headline Full;

src: url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Bold.woff2) format(“woff2”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Bold.woff) format(“woff”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Bold.ttf) format(“truetype”);

font-weight: 700;

font-style: normal;

}

@font-face {

font-family: Guardian Headline Full;

src: url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BoldItalic.woff2) format(“woff2”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BoldItalic.woff) format(“woff”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BoldItalic.ttf) format(“truetype”);

font-weight: 700;

font-style: italic;

}

@font-face {

font-family: Guardian Headline Full;

src: url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Black.woff2) format(“woff2”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Black.woff) format(“woff”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Black.ttf) format(“truetype”);

font-weight: 900;

font-style: normal;

}

@font-face {

font-family: Guardian Headline Full;

src: url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BlackItalic.woff2) format(“woff2”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BlackItalic.woff) format(“woff”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BlackItalic.ttf) format(“truetype”);

font-weight: 900;

font-style: italic;

}

@font-face {

font-family: Guardian Titlepiece;

src: url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-titlepiece/noalts-not-hinted/GTGuardianTitlepiece-Bold.woff2) format(“woff2”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-titlepiece/noalts-not-hinted/GTGuardianTitlepiece-Bold.woff) format(“woff”),

url(https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-titlepiece/noalts-not-hinted/GTGuardianTitlepiece-Bold.ttf) format(“truetype”);

font-weight: 700;

font-style: normal;

}

@media (min-width: 71.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive {

margin-left: 160px;

}

}

@media (min-width: 81.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive {

margin-left: 240px;

}

}

.content__main-column–interactive .element-atom {

max-width: 620px;

}

@media (max-width: 46.24em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-atom {

max-width: 100%;

}

}

.content__main-column–interactive .element-showcase {

margin-left: 0;

}

@media (min-width: 46.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-showcase {

max-width: 620px;

}

}

@media (min-width: 71.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-showcase {

max-width: 860px;

}

}

.content__main-column–interactive .element-immersive {

max-width: 1100px;

}

@media (max-width: 46.24em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-immersive {

width: calc(100vw – var(–scrollbar-width));

position: relative;

left: 50%;

right: 50%;

margin-left: calc(-50vw + var(–half-scrollbar-width)) !important;

margin-right: calc(-50vw + var(–half-scrollbar-width)) !important;

}

}

@media (min-width: 46.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-immersive {

transform: translate(-20px);

width: calc(100% + 60px);

}

}

@media (max-width: 71.24em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-immersive {

margin-left: 0;

margin-right: 0;

}

}

@media (min-width: 71.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-immersive {

transform: translate(0);

width: auto;

}

}

@media (min-width: 81.25em) {

.content__main-column–interactive .element-immersive {

max-width: 1260px;

}

}

.content__main-column–interactive p,

.content__main-column–interactive ul {

max-width: 620px;

}

.content__main-column–interactive:before {

position: absolute;

top: 0;

height: calc(100% + 15px);

min-height: 100px;

content: “”;

}

@media (min-width: 71.25em) {

.content__main-cFor interactive content columns, a left border is added with specific positioning and z-index. On larger screens, the border’s position adjusts slightly. Within these columns, atom elements have no top or bottom margins but include padding. When a paragraph follows an atom element, the padding is removed and margins are added instead. Inline elements are limited to a maximum width.

For figures with an inline role, they also have a maximum width on medium-sized screens and above.

Custom properties define various colors for elements like datelines, headers, captions, and features. The primary pillar color defaults to the feature color if not set.

Atom elements within interactive columns or generally have no padding. The first paragraph after specific elements or horizontal rules in various content bodies receives extra top padding.

Additionally, the first letter of these paragraphs is styled as a drop cap with a specific font, size, weight, and color, using custom properties for coloring.For paragraphs following horizontal rules in specific content areas, remove top padding.

Limit pullquote width to 620px in article, interactive, comment, and feature bodies.

For showcase element captions in main content and article containers, set position to static, width to 100%, and max-width to 620px.

Immersive elements should span the full viewport width minus the scrollbar. On screens up to 71.24em, cap their width at 978px. For captions on these screens, add 10px of horizontal padding, increasing to 20px on screens between 30em and 71.24em.

On mid-range screens (46.25em to 61.24em), limit immersive elements to 738px. On smaller screens (up to 46.24em), remove left margin, align to the left edge, and add a 10px negative left margin (20px on screens 30em and wider). Captions on these smaller screens get 20px of horizontal padding.

For the furniture wrapper on large screens (61.25em and up), use a CSS grid with defined columns and rows. Style the first child of headlines with a top border. Position the meta section relatively with top padding and no right margin. In standfirst sections, adjust bottom margins, set list item font size to 20px, and style links with underlines (using a custom color for the underline that changes on hover). The first paragraph in the standfirst gets a top border and no bottom padding, though this border is removed on very large screens (71.25em and up).

Also, for figures within the wrapper, remove left margin and set a max-width of 630px for inline elements. On the largest screens (71.25em and up), the grid template columns are defined starting from title, headline, and meta.The layout uses a grid with columns and rows defined for different screen sizes. On larger screens, the grid has three columns for the title, headline, and meta sections, five columns for the standfirst, and eight columns for the portrait, with rows sized proportionally. On medium screens, the grid adjusts to two, five, and seven columns respectively, with specific row heights.

Styling includes a top border for the meta section and a left border for the standfirst, both using a custom color variable. Headlines have a maximum width and font size that changes with screen size, becoming larger on wider screens. Some elements, like social sharing and comment sections, have borders matching the header color, while others are hidden on certain devices.

The standfirst text has specific padding and font properties, and the main media area is positioned within the grid, with its width adjusting on smaller screens to account for scrollbars and margins. Captions are positioned absolutely.The furniture wrapper’s figure caption is positioned absolutely at the bottom with no bottom margin, featuring padding, a background color, and text color. Its width is set to 100% with a minimum height of 46 pixels. Within the caption, the first span is hidden, while the second is displayed and limited to 90% of the maximum width. The caption’s text and SVG icons use a specific color variable.

On screens wider than 30em, the caption’s horizontal padding increases. A dedicated caption button is absolutely positioned at the bottom right, with a circular background and scaled SVG icon, adjusting its right position on larger screens.

For interactive main columns on very wide screens, a pseudo-element adjusts its top and height. Headings within these columns have a maximum width.

On iOS and Android, dark mode color variables are defined, including a feature color that changes in dark mode. Specific article containers on these platforms style the first letter of the first paragraph after certain elements with a secondary color, set the article header height to zero, adjust padding for the furniture wrapper, and hide the content labels within it.For iOS and Android devices, the following styles apply to feature, standard, and comment article containers:

– Labels: Use a bold, capitalized font in the Guardian headline or serif typeface, colored with the new pillar color variable.

– Headlines: Set to 32px, bold, with 12px bottom padding, and a dark gray color (#121212).

– Images: Positioned relatively, with a 14px top margin and negative 10px left margin. The width spans the full viewport (accounting for scrollbars), and the height adjusts automatically. Inner elements, images, and links within the figure have a transparent background, matching the full viewport width with automatic height.

– Standfirst (article summary): Includes 4px top padding, 24px bottom padding, and a negative 10px right margin. Paragraphs inside the standfirst inherit these container styles.The CSS code sets specific styles for article standfirsts and metadata on iOS and Android devices. It defines font families for the standfirst text and customizes link appearances, including color, underline style, and hover effects. The code also adjusts margins for metadata sections and ensures consistent styling for bylines and author links across different article types.The author’s name in the furniture wrapper’s meta section, along with related links and spans on Android devices for both standard and comment articles, should use the new pillar color. On iOS and Android, the meta miscellaneous section in feature, standard, and comment articles should have no padding, and any SVG icons within should be styled with the new pillar color as the stroke.

For showcase elements in feature, standard, and comment articles on both iOS and Android, the caption button should be displayed as a flex container. It should be centered with 5px padding, aligned both horizontally and vertically, sized at 28×28 pixels, and positioned 14px from the right.

The article body in feature, standard, and comment articles on iOS and Android should have 12px padding on the left and right. Within the article body, image figures that are not thumbnails or immersive should have no margin. Their width should be the full viewport width minus 24px and any scrollbar width, with an automatic height. The captions for these images should also follow these rules.For iOS and Android devices, immersive images in feature, standard, and comment articles should span the full viewport width, accounting for the scrollbar.

Blockquotes within the article body should use the site’s pillar color for their decorative element.

Links in the article text should be styled with the primary pillar color, an underline, and no background image. The underline color should change on hover.

In dark mode, the article header area should have a dark background. Labels and the headline should use specific colors for contrast, and introductory text should be legible against the dark theme.The text appears to be a fragment of CSS code, not a prose passage to rewrite. It contains selectors and style rules targeting specific elements on web pages for different platforms (iOS and Android) and article types (feature, standard, comment). The rules set colors and styles for links, author bylines, icons, image captions, and blockquotes using CSS custom properties (like `–new-pillar-colour` and `–dateline`).

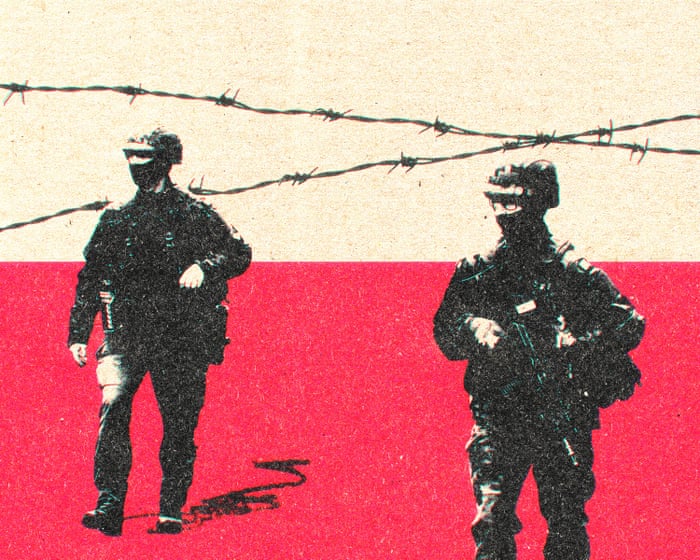

Since this is code, it cannot be rewritten into “fluent, natural English” without changing its fundamental purpose. If you intended to provide a different text for rewriting, please share it.This CSS code sets a dark background for specific elements on Android devices and styles the first letter of paragraphs on iOS devices. For Android, it applies a dark background to various article containers and body sections. For iOS, it targets the first letter of paragraphs that come after certain elements within different article containers, likely for drop cap styling.This appears to be a lengthy CSS selector targeting specific elements on iOS and Android platforms. The selector applies styles to the first letter of paragraphs following certain elements across different article containers and body sections.Cezary Pruszko still recalls the civil defense training from his school days under Communist rule—map reading, survival skills, and a palpable sense that the threat of war was real and constant. “My generation grew up with those dangers. You didn’t need to explain why it was important,” said the 60-year-old Pruszko, as he brushed up on those skills at an army base outside Warsaw on a chilly Saturday morning. Alongside dozens of other Polish civilians, he explored a bomb shelter, tried on gas masks, and practiced striking sparks from a flint to start a fire.

The training, intended to strengthen civilian resilience, is part of a new program that plans to train 400,000 Polish citizens by 2027. The voluntary initiative is available to everyone, from schoolchildren to retirees. “We are living in the most dangerous times since the end of the Second World War,” he said.At the launch of the programme earlier this month, Poland’s defence minister, Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz, stated, “Each of us must have the skills, knowledge and practical know-how to cope in a crisis.”

Poland is acutely aware that its geographical location at the centre of Europe has historically left it vulnerable to attack. The full-scale invasion of neighbouring Ukraine in 2022 sharpened this focus. This year, drone incursions into Polish airspace and a wave of sabotage attacks linked to Russian intelligence have heightened alarm. Most recently, a railway line was blown up earlier this month, with authorities claiming Russia organised the attack with the intent to cause casualties.

This has led to a complete overhaul of national security thinking. The government has approved a draft budget for next year that will raise defence spending to 4.8% of GDP—significantly higher than almost all other NATO countries. New buildings must now be fitted with bomb shelters, and a programme has begun to refurbish older, dilapidated shelters. Construction has also started on an “eastern shield” that will run the length of Poland’s borders with Belarus and the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad.

Revising the war games

At a forward operating base a few kilometres from Poland’s border with Belarus, Brigadier General Roman Brudło, commander of Poland’s 9th Armoured Cavalry Brigade, said Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has completely changed Poland’s security outlook.

“The quiet times have unfortunately passed, and we are living in a difficult, very dynamic period,” he said in an interview at his field office, located inside a container at the base. “I read the papers, I hear the news, I see the analysis from different intelligence communities, which say that in one, two, five years we could face a full-scale invasion from Russia. I don’t know. I hope not.”

Brudło joined the army in 1996 because he was a trained mechanic and “loved tanks.” After nearly three decades of service, including rotations with allied forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, he admitted that in a war involving drones or sabotage threats, his traditional warfare training would need to be updated.

“I’m not tied to the tank; I am not glued to it, and everybody here has also undergone training preparing us for new kinds of tasks,” he said. “I think [Russia] will put pressure on us in a hybrid way, below the threshold of war, to wear us down without crossing the line that would unite us.”

Captain Karol Frankowski, who works in communications for the brigade, described spending a month at NATO’s annual Saber Junction exercises in Germany over the summer. There, he wargamed alongside soldiers from more than a dozen countries. The scenario involved a hybrid attack from an unspecified aggressor, leading to a breakdown of law and order and the implementation of martial law.

“My job was to make contact with the locals during the crisis—they had actors playing the chief of police, local journalists, other citizens—and we had to act as if martial law was in effect,” he said.

According to Brudło and Frankowski, one of Russia’s hybrid tactics is encouraging “illegal migration” on Europe’s borders. The brigade’s current role is to help border guards detect people attempting to cross into Poland—and thus the Schengen zone—from Belarus. Sensors along the border wall alert soldiers to any crossing attempts. The day before The Guardian’s visit, the soldiers said they had apprehended a man from Afghanistan, who would most likely be returned to Belarus.

“For the pro-Protecting our country is a necessity. We don’t know who this Afghan man is. He could be a spy, or someone trying to destroy our country from within. Maybe he’s even a Russian spy,” said Frankowski.

The notion that Moscow and Minsk are using migration as a weapon was adopted by the previous nationalist government to justify a violent crackdown on border-crossing migrants since the crisis began in 2020. Notably, even after Donald Tusk’s progressive coalition took power two years ago, little has changed.

Aleksandra Chrzanowska, a member of the Grupa Granica alliance of activists and rights workers, said the focus on the Russian threat has led many liberals—who were once outraged by the brutal treatment of asylum seekers at the border—to now support the government’s tough policies. “The drama and tragedy of those coming here seeking protection no longer interests people,” she said.

Chrzanowska acknowledged that national security is important but called the portrayal of migrants as a threat a “far-right, racist narrative” not grounded in fact. She and other activists now stand as lonely voices advocating for the human rights of those trying to cross. The migration debate in Poland, as in many European countries, has shifted sharply to the right, and here the alleged link between migration and Russia makes the rhetoric even more potent.

Ready to Fight

In addition to the border wall built by the previous government along much of the Belarus frontier, the new “eastern shield” will involve trenches and fortifications along the borders with Belarus and Kaliningrad, creating a barrier against potential invasion.

But if war comes, it likely won’t be the traditional kind with tanks rolling across the border. The shield will also include GPS towers and other technological installations to guard against drone incursions.

In Gołdap, a town of about 15,000 people just a few kilometers from the Kaliningrad border, locals were calm about having Russia on their doorstep. “The threat does influence how you think, but honestly, I’d be more worried living in Warsaw. Strategically, they’re not going to target us here,” said Piotr Bartoszuk, 45, head of Gołdap’s vocational college.

He recalled that in the early 2000s, locals crossed the border regularly: Poles filled up with cheaper Russian petrol, while Russians came for shopping or sightseeing. Now, the border is closed; buildings that once housed a bar and exchange booth lie abandoned and overgrown with grass.

“Russia is definitely a threat, but not a huge one, because we’re in NATO, we’re protected, and I don’t think they’d attack us out of the blue like they did Ukraine,” said 15-year-old Kornelia Brzezińska, who hopes to join the army and is studying in the military track at the college.

If the country were attacked, however, she wouldn’t hesitate to fight. “I’d go to the front. I really do love Poland. It’s not something I say lightly. I wouldn’t abandon our nation—I’d defend it,” she said.

Outside, on the college building walls, shrapnel gouges in the red brick were left deliberately visible as a reminder of the devastation Poland suffered in World War II. Few survivors of that war remain today, but generational memories fuel fears about a potential new conflict, especially among older Poles.

As the training day at the military base outside Warsaw ended, Pruszko said he had also arranged for employees of his company to receive the same survival training.”Many younger employees have grown up in the EU during a time of peace, with little awareness of the dangers that we older generations remember. I hope we never need these skills, but I want them to know what to do if that moment ever comes,” he said.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQs I will defend our country Polands Readiness Amid Growing Threats

Here is a list of frequently asked questions about Polands increased focus on national defense and public readiness

BeginnerLevel Questions

1 What does I will defend our country refer to

Its a phrase that captures the current mood in Poland reflecting a strong sense of patriotism and a commitment to national defense as security threats particularly from Russia increase in Eastern Europe

2 Why is Poland so concerned about war right now

Poland shares a border with Ukraine and Russias Kaliningrad region The ongoing war in Ukraine has made the threat of conflict feel much closer and more immediate leading to serious preparations

3 Is there a mandatory military draft in Poland

No Poland has a professional army However there is increased focus on voluntary training modernizing the military and preparing civilian reserves

4 What is the Territorial Defence Force

The WOT is a relatively new branch of the Polish Armed Forces created in 2017 Its a parttime voluntary force of citizensoldiers focused on local defense supporting communities during crises and supplementing the professional army

5 How can an ordinary person help or prepare

Civilians can stay informed through official channels consider voluntary training programs and have a basic emergency plan and supplies for their household

Advanced Practical Questions

6 How is Polands military changing and modernizing

Poland is on a massive spending spree purchasing advanced tanks fighter jets missile systems and drones from allies like the US and South Korea to create one of NATOs most powerful land armies

7 What role does NATO play in Polands defense

Poland is a key NATO member The alliance has significantly increased its rotational troop presence in Poland and Article 5the collective defense clausemeans an attack on Poland is considered an attack on all NATO members

8 Are there common criticisms or problems with this push for readiness

Yes Critics point to the enormous cost potential strain on the economy the risk of escalating tensions and the challenge of integrating so much new equipment quickly Some also debate the balance between military deterrence and diplomatic efforts