I remember seeing As Good As It Gets in theaters as a teenager and being pleasantly startled by Jack Nicholson’s Melvin Udall, the ultimate romantic comedy grouch. He’s a bestselling romance author who disdains love, suffers from OCD but weaponizes it, and is a New Yorker who hates crowds—who can’t relate? In one scene, an adoring fan asks Melvin his secret to writing women. “I think of a man, and I take away reason and accountability,” he says, a line forever seared in my memory. Of course, Melvin’s anti-charm offensive only goes so far in a James L. Brooks film. Soon, his rudeness softens as he’s forced on a journey of self-discovery with the neighbor he can’t stand (Greg Kinnear) and the diner waitress he can’t live without (Helen Hunt). Melvin emerges changed by the end but keeps the essence of his grouchy charm. That was the moment I fell in love with the writer’s life. — Andrew Lawrence

As Good As It Gets is available on Netflix in the US, to rent digitally in the UK, and on Binge in Australia.

In the acidic 2011 black comedy Young Adult, things don’t go as Mavis Gary expected. The middling YA ghostwriter, borderline alcoholic, and self-described “psychotic prom queen bitch” storms back to her hometown to “save” her high school boyfriend Buddy, convinced he’s miserable and desperate to escape his life—complete with an ugly baby, a cardigan-wearing wife, and a shabby chic suburban home. But it’s Mavis, played by an astonishingly awful Charlize Theron, who is truly miserable: a stunted, peaked-in-high-school bully unable to move on from her glory days. The film subverts expectations, with Diablo Cody’s daring character study refusing to give Mavis the redemptive arc we’re used to. Instead, it brings her close to self-realization before pulling her back into darkness. I never tire of rewatching Mavis—deluded, drunk, and devoid of empathy—stubbornly resisting change. There’s something both bitterly realistic and selfishly reassuring about watching her slide from the relatable (like a sneering drive through her generic hometown) to the tragic (recalling a high school miscarriage and fears her body is broken) to the monstrous (telling Buddy’s kind wife she hates her, which feels like watching a puppy get kicked). Mavis goes far over the edge, but I never would. Right? — Benjamin Lee

Young Adult is available on Kanopy and Hoopla in the US and to rent digitally in the UK and Australia.

The Coen brothers have always specialized in dislikable protagonists. From their debut, Blood Simple, it was hard to decide who was more irritating: Frances McDormand’s self-absorbed Abby, John Getz’s gormless Ray, or M. Emmet Walsh’s smug private eye Loren Visser. Their filmography is a parade of difficult characters: Gabriel Byrne’s duplicitous Tom Reagan in Miller’s Crossing, George Clooney’s smirking Ulysses Everett McGill in O Brother, Where Art Thou?, and Oscar Isaac’s super-irritating folk singer in Inside Llewyn Davis. (While not exactly hateful, Michael Stuhlbarg’s Larry Gopnik in A Serious Man is a prime example of what used to be called a wet blanket.) In the spirit of booing at the screen…Considering the superb Marty Scorsese, I’d like to point out that every one of these films is brilliant—and perhaps in the chef’s kiss of Coen brothers counterintuition, arguably their greatest film contains their most annoying protagonist: Barton Fink. (Even his name is irritating.) Fink is painfully awkward and overweeningly arrogant, neurotically intellectual and self-centeredly unaware, supercilious and chip-on-the-shoulderish, all at the same time. He couldn’t be more dislikeable… and yet, like Marty, it gives the character a restless, questing energy that makes him a compelling magnet for everything that happens. What saves both of them (or “redeems” in script-readers’ terms) is that neither is actively horrible or evil; there’s some spark of morality underneath it all. I suppose we should be grateful for small mercies. —Andrew Pulver

Barton Fink is available on the Criterion Channel in the US, YouTube in the UK, and to rent digitally in Australia.

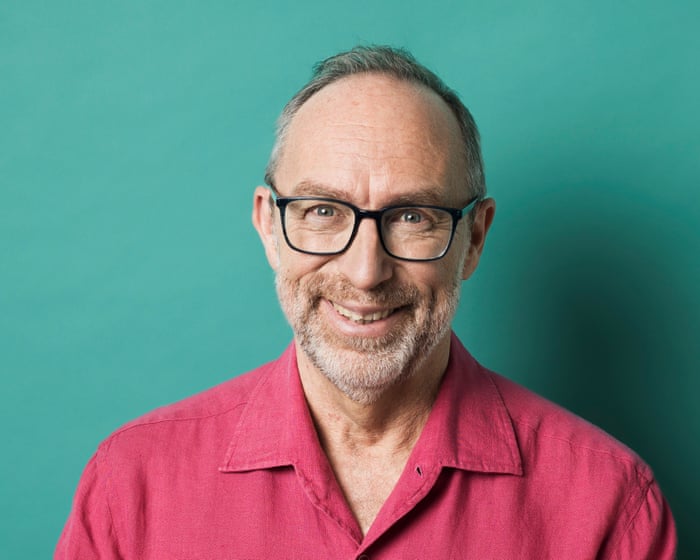

Wren – Smithereens

Consider Smithereens the grittier older sister of Desperately Seeking Susan, director Susan Seidelman’s better-known Madonna vehicle. Obnoxious does not begin to accurately describe its hero, Wren, a New Jersey refugee who flees to New York hoping to make it big in the punk scene. (Doing what exactly is beside the point.) She’s a charmless social climber who constantly big-leagues her only friend, a van-dwelling beatnik type named Paul. Instead, she has her eyes on a fictionalized version of Richard Hell, played by the Voidoid himself. (Wouldn’t you?) I give Wren maybe too many passes. I love her fabulous outfits—someday I hope to find a dupe of the fuzzy pink coat she wears waiting for me at a thrift store—and the way she wakes up every morning after ripping her life to shreds the night before. Sure, Wren’s aloof, rude, and manic in her desires. Male leads have gotten away with much worse for the entirety of film history. I can’t help but root for her. —Alaina Demopoulos

Smithereens is available on HBO Max and the Criterion Channel in the US, Amazon Prime in the UK, and Plex in Australia.

Ingrid Thorburn – Ingrid Goes West

No one can argue that Ingrid, a deeply unwell woman played by Aubrey Plaza in Matt Spicer’s underrated 2017 thriller Ingrid Goes West, does the right things. We meet her fresh out of a psychiatric facility, where she was sent after pepper-spraying a bride at a wedding she wasn’t invited to, and follow her west, where she latches onto the persona projected online by influencer Taylor (Elizabeth Olsen) and wheedles her way into her avocado-toast life. And yet I still root for Ingrid, as she personifies a dark and underexplored part of all our internet-addled brains—the part that implicitly understands the precise currency of envy in our culture, that fixates on certain faces, that remembers the exact details of a stranger’s engagement party. That relishes comeuppance, craves validation, and burns with corrosive anger when everyone from wannabe influencers to celebrities wins the attention economy with obvious falsehoods (Kendall Jenner’s claim that Accutane permanently shrinks your nose? Please.) A part of me gets Ingrid’s quest, her disillusionment, and rage. I do not endorse vigilante accountability for the fake and successfully boring, but I do enjoy watching it. —Adrian Horton

Ingrid Goes West is available on Kanopy in the US, YouTube in the UK, and to rent digitally in Australia.

Patrick Bateman – American Psycho

After many failed attempts to adapt American Psycho into a film—including a cracked screenplay written by Bret Easton Ellis that ended up atop the World Trade Center, and potential involvement from directors like…After interest from David Cronenberg, Brad Pitt, Oliver Stone, and even Leonardo DiCaprio, the project ultimately went to the relatively unknown Mary Harron. Fresh off her film I Shot Andy Warhol at Cannes, she completed a screenplay with actor Guinevere Turner and cast Christian Bale as the star. Harron’s satire of toxic masculinity and corporate greed is as dark as they come. There’s the infamous scene where serial killer Patrick Bateman tries to feed a stray cat to an ATM, and the running joke is that being a sociopathic murderer fails to make him stand out from his colleagues in finance. Bateman’s utter odiousness is essential to the film’s schizoid world, where he robotically delivers a soliloquy on Phil Collins before staging a porn shoot with two sex workers, or holds a nail gun to his unknowing secretary’s head while toying with the idea of seducing her. All of this constructs an aesthetic realm of slick surfaces—a film about the loneliness and emptiness of sociopathy, the ultimate hell of living in a world where nothing you do matters. There’s a reason Harron’s feminist revision of the book has steadily gained a cult following as the world moved from the placid 1990s into a new Gilded Age ruled by the likes of Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and Donald Trump. Bale’s Bateman may be utterly unlikable, but he’s far from unrecognizable. —Veronica Esposito

American Psycho is available on Amazon Prime and the Criterion Channel in the US, and on Netflix in the UK and Australia (also on Stan in Australia).

Roger Greenberg – Greenberg

Watch certain groups of Noah Baumbach films—his early comedies, his collaborations with Greta Gerwig, or his newer work—and you might not think of him as chronicling especially unlikable characters. Many are downright charming. But between 2005 and 2010, his movies can feel like endurance exercises for the cringe-averse. This is especially true of the title character in his 2010 film Greenberg, played by Ben Stiller. Many Baumbach protagonists struggle with the disappointments of aging, whether in their teens, twenties, thirties, or, in Greenberg’s case, mid-forties. Stiller, with his prickly comic style and talent for fixating on details, turns that struggle into something both symphonic and redolent of a stubborn, lonely solo. What makes the unemployable-seeming Greenberg—a middling handyman and ex-musician who can barely handle dog-sitting for his brother—so delightful to me is his ill-timed but honest rage bombs, whether carefully set (like a series of hilariously petty complaint letters) or thrown with self-conscious self-destructiveness (he modifies “youth is wasted on the young” to “life is wasted on people”). He’s abrasive, self-centered, and caustic in a way that certain viewers will find uncomfortably relatable. The film understands that insecure, adolescent impulses don’t always emerge as frat-boy immaturity; sometimes they come from very real frustrations with how life defies expectations. —Jesse Hassenger

Greenberg is available to rent digitally.

Pansy Deacon – Hard Truths

Pansy Deacon is the sort of brutally unlikable character who finds little, if any, redemption. She remains pretty much awful from beginning to end in Mike Leigh’s shattering 2024 character study, Hard Truths. There is a moment of cathartic laughter in the film, and a scene of something like reconciliation between Pansy and her cheerful sister. But otherwise, Leigh and actor Marianne Jean-Baptiste present a portrait of a woman whose bitterness and cruelty seem almost absolute.Anne Jean-Baptiste’s terrifying creation remains a powerful source of resentment, anxiety, and cruelty. She is a stunning character—loathsome and only faintly pitiable. Pansy is so vividly miserable that, beyond some critics’ groups, awards bodies seemed unable to welcome Jean-Baptiste into their festivities last year. That was disappointing, but the snub also stands as a testament to the dazzling, exacting craft of Hard Truths. I still find myself thinking of Pansy from time to time, foolishly hoping she’s found a way out of her malaise, while knowing she would likely swat away such sentiment with a derisive laugh or a monologue about how pointless it is to care for her. —Richard Lawson

Hard Truths is available on Paramount+ in the US, Netflix in the UK, and for digital rental in Australia.

Daniel Plainview – There Will Be Blood

As spirit animals go, Daniel Plainview isn’t one you’d rush to adopt, but there’s something irresistibly bracing about his approach. Rarely a week goes by without the line, “I can’t keep doing this on my own, with these… people,” popping into my head. Yes, he’s flawed—a cold-hearted, child-abandoning, resource-sucking murderer, etc.—but he’s also exhilaratingly focused and honest (the clue is in the name). Playing devil’s advocate, he’s also very good at his job, at times a sweet and loving parent, and, when it comes to false prophets at least, absolutely right. Quentin Tarantino thinks There Will Be Blood doesn’t work because of Paul Dano—which is nonsense, of course, because the film isn’t intended as a two-hander (and Dano is great anyway). What’s certain is that the movie wouldn’t work if its tar-hearted antihero weren’t also funny, formidable, and—dare I say it—relatable. Plus, he loves bowling! —Catherine Shoard

There Will Be Blood is available on Paramount+ in the US and UK, and on Stan in Australia.

Charles Foster Kane – Citizen Kane

Charles Foster Kane is the towering blueprint for so many cynical and enduring cinematic figures who both enthrall and repel us. Think of Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood or Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network—characters who exist a century apart, yet live in Kane’s shadow, embodying an American dream that is insatiable, corruptible, and often fueled by contempt. For at least half a century, Citizen Kane was widely named the greatest film of all time (chiefly on the Sight & Sound critics’ poll), largely celebrated for its form—its use of deep focus is taught in almost every introductory film class. But the film’s emotional power comes from Orson Welles’s enigmatic portrayal of the predatory and rather pathetic Kane, the media baron inspired by William Randolph Hearst and admired by Donald Trump. Kane preaches about speaking truth to power, but only when it serves him. His youthful idealism and principles are as thin and disposable as the paper they’re printed on. It’s easy to be seduced by his ambitions, not to mention the bluster and silky-smooth charisma he skillfully wields, before it all sours and curdles—much like the American dream itself. —Radheyan Simonpillai

Citizen Kane is available for digital rental in the US, on BFI Player and iPlayer in the UK, and for digital rental in Australia.

Marla Grayson – I Care A Lot

If Rosamund Pike were standing in front of a decimated building holding a bomb detonator, telling me she didn’t do anything, I could believe her. There’s a je ne sais quoi to her characters’ malice that invites you to reconsider definitions of right and wrong—where the bottom line is…A vicious heart is still a heart. As she did in Gone Girl, Rosamund Pike—with her velvet voice and razor-sharp bob—channels self-righteousness into I Care a Lot’s Marla Grayson, creating a perfect stone-cold yet sweetly smiling antihero. In this 2020 crime thriller, Grayson is a court-appointed legal guardian who acts like an aggressive leech, draining vulnerable, helpless elderly people of their savings. She is more sharp-tongued and seasoned than Amy Dunne, the first-time killer in Gone Girl, and at almost every turn, you can’t tell whether she’s about to offer a comforting hug or bait an elderly person into attacking her—both of which happen. Grayson exposes a nasty, quiet strand of greed that exists in many of us: if you could take someone’s money for yourself without anyone really knowing—if you’re beautiful, have experienced love, and are devilishly self-aware—then it’s somehow acceptable to force drugs into a man’s body or convince a judge that someone is going senile. Preying on society’s most vulnerable is heinous, but when Pike appalls you, she also delivers a little thrill with it: you feel a bit more alive.

I Care A Lot is available on Netflix in the US and on Amazon Prime in the UK and Australia.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQs Uncomfortably Relatable Flawed Film Characters

Beginner General Questions

1 What does uncomfortably relatable mean in this context

It describes the feeling of recognizing a part of yourself in a fictional character whose flaws mistakes or negative traits are so honest and human that it makes you cringe a little with selfrecognition

2 Why would anyone like a flawed character

Because perfect characters are often boring and unrealistic Flawed characters feel more authentic complex and human Their struggles teach us about resilience growth and the messy nature of life

3 Can you give me a classic example of an uncomfortably relatable character

A common example is Lester Burnham from American Beauty His midlife crisis feelings of emptiness and desperate search for meaning are painfully familiar to many adults even if we dont act on them the same way

4 Isnt it bad to relate to a bad character

Not necessarily Relating to a characters flaw doesnt mean you endorse their worst actions Its about understanding the human emotions that drive behavior which can lead to greater selfawareness and empathy

5 Whats the benefit of discussing these characters

These discussions can be a safe indirect way to explore difficult emotions and personal flaws They spark conversations about morality mental health and the human condition often making us feel less alone in our own imperfections

Advanced Deeper Questions

6 Whats the difference between a flawed character and an antihero

An antihero is a type of flawed protagonist who lacks conventional heroic qualities but still drives the story All antiheroes are flawed but not all flawed characters are antiheroes A flawed character can be a supporting role or even a villain

7 How do authors or filmmakers make a flawed character likable or compelling

They often use techniques like showing the characters vulnerability giving them a redeeming quality ensuring their motivations are understandable or placing them in a worse situation than themselves

8 Can a character be too flawed to be relatable

Yes If a