This text defines a custom font family called “Guardian Headline Full” with multiple font weights and styles. It specifies the font files in different formats (WOFF2, WOFF, and TrueType) and their online locations for the browser to load when needed. The definitions include light, regular, medium, and semibold weights, each with normal and italic styles.This CSS code defines several font families for the Guardian Headline and Guardian Titlepiece fonts, specifying their sources in different formats (WOFF2, WOFF, and TrueType) along with their font weights and styles. It also includes responsive design rules for the main content column in interactive layouts, adjusting margins, widths, and positioning based on viewport size. For instance, on wider screens, it adds a left margin and a border, while on smaller screens, it adjusts element widths and positions to fit the display. The styles ensure that elements like paragraphs, lists, and immersive content adapt appropriately across devices.For the main interactive content column, a left border is added before the element, positioned 11 pixels to the left. Within this column, atoms have no top or bottom margin but 12 pixels of padding on both ends. When a paragraph follows an atom, the padding is removed, and margins of 12 pixels are applied instead. Inline elements are limited to a maximum width of 620 pixels, and for screens wider than 61.25em, inline figures with a specific role also adhere to this width limit.

Color variables are defined for various elements, such as dateline, header border, caption text, and background, with a feature color set to red and a new pillar color defaulting to the feature color. Atoms in the main column or elsewhere have no padding.

For the first paragraph following specific elements like atoms, sign-in gates, or horizontal rules in different content areas (article body, interactive content, comments, features), a top padding of 14 pixels is added. Additionally, the first letter of these paragraphs is styled with a specific font family, bold weight, large font size, uppercase text, floated to the left, and colored using a variable for drop caps or the new pillar color.

If a paragraph comes after a horizontal rule in these content areas, the top padding is set to zero.Pullquotes within specific content areas should not exceed 620 pixels in width.

For showcase elements in main articles, features, standard articles, and comments, captions should remain in their normal position, span the full width, and be limited to 620 pixels.

Immersive elements should span the full viewport width, accounting for scrollbars. On screens smaller than 71.24em, these elements are capped at 978 pixels wide with 10px side padding for captions. Between 30em and 71.24em, caption padding increases to 20px.

Between 46.25em and 61.24em, immersive elements max out at 738 pixels. Below 46.24em, they align to the left edge with no right margin and 10px left inset, increasing to 20px between 30em and 46.24em, where captions also get 20px padding.

For larger screens (61.25em and up), the furniture wrapper uses a grid layout with defined columns and rows. Headlines get a top border, meta information is positioned relatively with top padding, and standfirst text has specific styling: list items at 20px font size, links underlined without borders or backgrounds, changing color on hover, and first paragraphs with top borders except on very large screens (71.25em+).

Figures within the wrapper have no bottom margin and a 10px left inset, with inline elements limited to 630 pixels. On the largest screens, the grid adjusts its column structure.The layout uses a grid with specific columns and rows for different screen sizes. For smaller screens, the grid has three columns and rows with fixed and automatic heights, while larger screens adjust the row heights proportionally.

Elements like the meta section have a top border line, and the standfirst section features a vertical line on the left. Headlines are styled with a maximum width and font size that increases on larger screens, and some elements are hidden or adjusted in margin and padding based on the viewport.

The main media area is positioned within the grid and spans the full width on mobile devices, with captions styled to appear at the bottom with a background color. Social and comment elements in the meta section have borders matching the header color, and certain components are not displayed.The furniture wrapper sets a dark background and adjusts margins and padding for different screen sizes. On larger screens, it adds sidebars with matching backgrounds and borders.

Headlines use bold, light gray text, while article titles and social buttons adopt a custom color (like a dark mode feature color). Social buttons have a border and change color on hover, with the background and icon colors swapping.

Captions are styled with specific colors and visibility controls, including a toggle button that appears as a small circle in the bottom right. Media queries adjust padding and element positioning for tablets and desktops, ensuring proper spacing and alignment across devices.This CSS code styles elements within a furniture-wrapper class, setting colors, borders, and layout for different screen sizes. It defines link colors and hover effects using CSS variables for meta and standfirst sections, with text decorations and offsets. Media queries adjust the layout for various viewport widths, creating sidebars with borders and background colors that scale accordingly. Social and comment elements in the meta section are also styled, with SVG strokes matching the header border color.The comment section has a border color that matches the header’s border color.

For article headings (h2) in the main body or interactive content, the font weight is set to light (200). However, if an h2 heading contains a strong element, it uses a bold font weight (700).

Additionally, the Guardian Headline Full font family is defined with various weights and styles, including light, regular, medium, and semibold, in both normal and italic forms. Each font file is sourced from specific URLs in WOFF2, WOFF, and TrueType formats.This CSS code defines several font families and their variations for the Guardian website. It specifies different font weights and styles (like bold, italic) for the “Guardian Headline Full” font, providing multiple file formats (WOFF2, WOFF, TTF) for cross-browser compatibility. Additionally, it includes the “Guardian Titlepiece” font in bold weight.

The code also sets up CSS custom properties (variables) for colors, adjusting them for dark mode preferences on iOS and Android devices. It includes specific styling for the first letter of paragraphs in article containers on these mobile platforms, ensuring a consistent typographic treatment across different contexts.For Android devices, the first letter of the first paragraph in standard and comment articles is styled with a secondary pillar color. On both iOS and Android, article headers are hidden, and furniture wrappers have specific padding. Labels within these wrappers use a bold, capitalized font in a headline style with a new pillar color. Headlines are set to 32px, bold, with bottom padding and a dark color. Images in furniture wrappers are positioned relatively, extend to the viewport width minus scrollbar width, and have auto height, with inner elements and links styled accordingly.For Android devices, images within article containers are set to have a transparent background, span the full viewport width minus the scrollbar, and adjust their height automatically.

On both iOS and Android, the standfirst section in articles has top and bottom padding of 4px and 24px respectively, with a right margin offset of -10px. The text inside uses the Guardian Headline font family or fallback serif fonts.

Links within the standfirst on both platforms are styled with a specific color, underlined with a 6px offset, and use a light gray underline that changes to the pillar color on hover. They have no background image or border.

Additionally, the meta section in article containers applies to both iOS and Android devices.For Android devices, remove margins from meta elements in standard and comment article containers.

For iOS devices, set the color of byline and author elements in feature, standard, and comment article containers to the new pillar color. Also, remove padding from meta miscellaneous elements and set the stroke of their SVG icons to the new pillar color. Additionally, style the caption button in showcase elements with specific display, padding, alignment, and dimensions.

For both iOS and Android, set the article body padding to 0 on the sides and 12px on top and bottom in feature, standard, and comment article containers.For iOS and Android devices, in feature, standard, and comment article containers, images that are not thumbnails or immersive will have no margin, a width of the full viewport minus 24 pixels and the scrollbar width, and an automatic height. Their captions will have no padding.

Immersive images in these containers will span the full viewport width minus the scrollbar width.

Quoted blockquotes in the article body will display a colored marker using the new pillar color.

Links within the article body will be styled with the primary pillar color, underlined with an offset, and use the header border color for the underline. On hover, the underline color changes to the new pillar color.

In dark mode, the furniture wrapper background will be set to a dark gray (#1a1a1a).For iOS and Android devices, apply the following styles to feature, standard, and comment article containers:

– Set the text color of content labels to the new pillar color.

– Remove the background color from headlines and set their text color to the header border color, ensuring this takes priority.

– Make the text in standfirst paragraphs match the header border color.

– Use the new pillar color for links in standfirst sections and for author bylines (including linked author names).

– Apply the new pillar color to the stroke of miscellaneous metadata icons.

– Set the color of captions for showcase images to the dateline color.

– For quoted text within the article body, use the appropriate styling.For iOS and Android devices, the text color of quoted blocks in article bodies is set to a specific pillar color.

Additionally, the background color for various article body sections on both iOS and Android is changed to a dark background, ensuring it overrides any other styles.

Furthermore, for the first letter following certain elements in article bodies on iOS, a special styling is applied, though the exact style isn’t specified here.This CSS code targets the first letter of paragraphs that follow specific elements within various article containers on iOS and Android devices. It applies to different sections like article bodies, feature bodies, comment sections, and interactive content, ensuring consistent styling for drop caps or initial letter formatting across the platform.This CSS code defines styles for specific elements on Android and iOS devices. It sets the color of the first letter in paragraphs following certain elements to white or a custom variable color. It also adjusts padding and margins for standfirst elements in comment articles, sets font sizes for h2 headings, and modifies padding for caption buttons differently on iOS and Android.

For dark mode preferences, it changes various color variables to lighter shades and defines a dark background color. Additionally, it makes article headers invisible by setting their opacity to zero and applies these styles to furniture wrappers in feature, standard, and comment article containers on both operating systems.For iOS and Android devices, the article container’s furniture wrapper has no margin. Labels in feature, standard, and comment articles use a specific color variable. Headlines in these articles are set to a light gray color. Links in article headers and title sections adopt the same color variable as the labels. A repeating linear gradient is applied as a background before meta sections, creating a patterned border. The byline text within meta areas is also displayed in light gray.For iOS and Android devices, the following styles apply to links within the meta section of feature, standard, and comment article containers:

– Links are colored using the new pillar color or a dark mode feature color.

– SVG icons in the meta miscellaneous section have their stroke set to the same color.

– Alert labels display in a light gray color (#dcdcdc) with important priority.

– Spans with data-icon attributes also adopt the new pillar or dark mode feature color.For iOS and Android devices, the color of icons in the meta section of feature, standard, and comment article containers is set to the new pillar color or a dark mode feature color.

On larger screens (71.25em and above), the meta section in these containers displays a top border using the new pillar color or the header border color. The miscellaneous meta content is then shifted 20 pixels to the right without any other margins.

Additionally, paragraphs and lists within the article body of these containers are limited to a maximum width of 620 pixels.

For quoted blockquotes in the article body, a specific style is applied before the content.For quoted blockquotes in articles, the color before the quote uses the secondary pillar color on both iOS and Android.

Links within article bodies on iOS and Android are styled with the primary pillar color, no background image, an underline 6px below the text, and a light gray underline color. When hovered over, the underline changes to the secondary pillar color.

In dark mode, the color for quoted blockquotes and links switches to the dark mode pillar color, and hovered links also use this color for their underline.

For apps, various text and icon colors are defined using custom properties, such as light gray for follow text and standfirst, and new pillar colors for icons, links, and bylines. The byline text color is set to the new pillar color, and a background image is applied to specific elements with a header border color.

In light mode for apps, images within sponsor links are inverted.

Additionally, the Guardian Headline Full font is defined with light and light italic weights, sourced from specific URLs in woff2, woff, and ttf formats.The font family “Guardian Headline Full” includes multiple styles with different weights and italics. Each style is available in WOFF2, WOFF, and TrueType formats from the specified URLs. The weights range from light (300) to bold (700), with both normal and italic variations for most weights.@font-face {

font-family: ‘Guardian Headline Full’;

src: url(‘https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BoldItalic.ttf’) format(‘truetype’);

font-weight: 700;

font-style: italic;

}

@font-face {

font-family: ‘Guardian Headline Full’;

src: url(‘https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Black.woff2’) format(‘woff2’),

url(‘https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Black.woff’) format(‘woff’),

url(‘https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-Black.ttf’) format(‘truetype’);

font-weight: 900;

font-style: normal;

}

@font-face {

font-family: ‘Guardian Headline Full’;

src: url(‘https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BlackItalic.woff2’) format(‘woff2’),

url(‘https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BlackItalic.woff’) format(‘woff’),

url(‘https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-headline/noalts-not-hinted/GHGuardianHeadline-BlackItalic.ttf’) format(‘truetype’);

font-weight: 900;

font-style: italic;

}

@font-face {

font-family: ‘Guardian Titlepiece’;

src: url(‘https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-titlepiece/noalts-not-hinted/GTGuardianTitlepiece-Bold.woff2’) format(‘woff2’),

url(‘https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-titlepiece/noalts-not-hinted/GTGuardianTitlepiece-Bold.woff’) format(‘woff’),

url(‘https://assets.guim.co.uk/static/frontend/fonts/guardian-titlepiece/noalts-not-hinted/GTGuardianTitlepiece-Bold.ttf’) format(‘truetype’);

font-weight: 700;

font-style: normal;

}

:root {

–person-2: #0077b6;

–person-3: #22874d;

–person-4: #ab0613;

–person-5: #c74600;

–person-6: #6b5840;

–person-7: #7d0068;

–person-8: #0c7a73;

–person-9: #003c60;

–person-10: #3f464a;

}

@media (prefers-color-scheme: dark) {

:root[data-rendering-target=”apps”] {

–person-2: #c1d8fc;

–person-3: #58d08b;

–person-4: #ff9081;

–person-5: #ff9941;

–person-6: #e7d4b9;

–person-7: #ffabdb;

–person-8: #69d1ca;

–person-9: #90dcff;

–person-10: #eff1f2;

}

}

.interview-chat-block.person-2 strong { color: var(–person-2); }

.interview-chat-block.person-2.single-interviewee strong { color: var(–textblock-text); }

.interview-chat-block.person-3 strong { color: var(–person-3); }

.interview-chat-block.person-4 strong { color: var(–person-4); }

.interview-chat-block.person-5 strong { color: var(–person-5); }

.interview-chat-block.person-6 strong { color: var(–person-6); }

.interview-chat-block.person-7 strong { color: var(–person-7); }

.interview-chat-block.person-8 strong { color: var(–person-8); }

.interview-chat-block.person-9 strong { color: var(–person-9); }

.interview-chat-block.person-10 strong { color: var(–person-10); }

:root {

–article-background: #ffffff;

–interviewer-background: #f6f6f6;

}

@media (prefers-color-scheme: dark) {

:root[data-rendering-target=”apps”] {

–article-background: #1a1a1a;

–interviewer-background: #000000;

}

}

[data-gu-name=”body”] .interview-chat-wrapper {

max-width: 620px;

}

@media (min-width: 46.25em) {

[data-gu-name=”body”] .interview-chat-wrapper {

padding: 20px 60px;

}

}

[data-gu-name=”body”] .interview-chat-block {

width: max-content;

max-width: 80%;

border: 1px solid var(–interviewer-background);

background-color: var(–article-background);

border-radius: 4px;

margin-bottom: 14px;

padding: 2px 8px 4px;

overflow: hidden;

}

[data-gu-name=”body”] .interview-chat-block p {

margin-bottom: 4px;

}

[data-gu-name=”body”] .interview-chat-block p strong {

display: block;

}

[data-gu-name=”body”] .interview-chat-block.interviewer {

margin-left: auto;

background-color: var(–interviewer-background);

}

[data-gu-name=”body”] .interview-chat-block.interviewer a {

border-bottom: 1px solid var(–article-border);

display: block;

width: max-content;

transition: border 0.3s ease-in-out;

}

[data-gu-name=”body”] .interview-chat-block.interviewer a:hover {

border-bottom: 1px solid var(–article-link-text);

}

[data-gu-name=”body”] .interview-chat-block.person-1 + .person-1 p strong,

[data-gu-name=”body”] .interview-chat-block.person-2 + .person-2 p strong {

display: none;

}During the first 17 minutes of Esau Lopez’s life, as he was deprived of oxygen, the atmosphere in the room remained calm and even joyful. Soft music played from a speaker in a modest Pennsylvania apartment. “You are a queen,” whispered one of three friends present.

Only his mother, Gabrielle Lopez, sensed something was wrong. Despite her efforts, her son wasn’t being born. “Can you help him out?” she asked when Esau’s head appeared. “Baby is coming,” her friend reassured. Four minutes later, Lopez repeated, “Can you grab him?” Another friend murmured, “Baby is safe.” After six more minutes, she asked again.

Lopez couldn’t see the umbilical cord around her son’s neck or the bubbles from his mouth. She didn’t realize his shoulder was stuck against her pelvis. But instinctively, she says, “I knew he was stuck.”

Esau was experiencing shoulder dystocia, where the head is born but the body doesn’t follow. Medical professionals are trained to handle this, which happens in about 1% of births. However, since Lopez was freebirthing—giving birth without medical assistance—no one present understood that each passing minute was causing irreversible brain damage. In a medically supervised birth, a five-minute delay would be an emergency; 17 minutes is unimaginable.

With immense effort, Lopez pushed, and Esau was born at 10 pm on October 9, 2022. He was limp, pale, with purple legs—signs of severe oxygen deprivation. He only made a faint gurgle. His father, Rolando, handed him to Lopez. “Do you think he needs air?” she asked. “He’s good,” her friend replied. Lopez held her motionless son, her eyes wide with fear.

Everyone in the room was frightened but hid it. Expressing their fear felt like a betrayal—not just of Lopez and her ability to give birth, but of the very idea of birth itself.As the minutes dragged on and Esau remained still, Lopez and her three friends recalled the teachings of their mentor, Emilee Saldaya, founder of the Free Birth Society: birth is safe. Trust the process. They pushed back their growing fear and waited. “It felt,” one of Lopez’s friends later said, “like we had stepped into a time warp.”

Lopez had met her friends through the Free Birth Society (FBS), an organization that advocates for freebirth—giving birth without any medical assistance, unlike home births where a midwife is present. FBS promotes an extreme version of freebirth, even within freebirth circles: it opposes ultrasounds, falsely claiming they harm babies, minimizes serious medical risks, and encourages “wild pregnancy,” which means no prenatal care at all.

FBS was started by former doula Emilee Saldaya, and many women discover it through its popular podcast, which has been downloaded 5 million times, its Instagram account with 132,000 followers, its YouTube channel with nearly 25 million views, or its bestselling video course, The Complete Guide to Freebirth. Co-created by Saldaya and another ex-doula, Yolande Norris-Clark, the course is available for download from FBS’s professional-looking website. According to forensic accountant Stacey Ferris of Virginia Polytechnic Institute, FBS has earned over $13 million in revenue since 2018.

Lopez was captivated by the podcast from the start, listening almost daily. She paid $299 to join FBS’s private online community, the Lighthouse, where she met the three friends who were with her when Esau was born. To prepare for her freebirth, she bought The Complete Guide to Freebirth for $399 in May 2022—a significant expense for the 23-year-old nanny at the time.

After spending hundreds of hours immersed in FBS content, Lopez became convinced that freebirthing was the safest way to have her baby, free from unnecessary medical procedures. Earlier during her three-day labor, she had gone to the hospital for an ultrasound because the baby wasn’t moving as much as usual. Staff warned her she was at high risk for shoulder dystocia, noting the baby was “huge,” and urged her to stay. But Lopez wasn’t worried. She remembered a newsletter from Norris-Clark stating that fears about shoulder dystocia were “greatly exaggerated.” From the FBS guide, she had learned that “women’s bodies do not grow babies that we cannot birth.”

After several minutes with Esau still not breathing, the tense atmosphere in Lopez’s bedroom shattered. Lopez immediately began performing CPR on her son while one friend looked up instructions online and another called 911. Paramedics resuscitated Esau, and he was taken to pediatric intensive care, where he stayed for 21 days. He had suffered hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, a brain injury caused by lack of oxygen.

Now three years old, Esau is severely disabled and fed through a tube. “He is a sweet, sensitive boy,” Lopez says. “He wants to do things like other children but gets frustrated because his body won’t let him.” Esau loves Ms. Rachel, Sesame Street, and watching his parents blow bubbles. When he learned to turn the page of a picture book, Lopez was thrilled: “The small gains are huge for us.”

Reflecting on who she was during her pregnancy, Lopez sometimes finds it hard to recognize herself. With the distant hum of a highway in the background as Esau plays with his toys, she tries to explain how she became so involved with FBS. “Nobody joins a cult willingly,” she says. “You think you’re joining a great movement.”

Dressed in a flowing white robe, Saldaya wore a gold crown shaped like the sun’s rays. Her most devoted followers sat around her in a circle in a shaded meadow. It was Ju—In 2021, one hundred women gathered for the first annual Matriarch Rising, a women-only festival held on Saldaya’s 53-acre property in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains. “All of these women,” recalls Serendipiti Day, 34, a former FBS employee, “were gathered around her with their notebooks, writing down every word.”

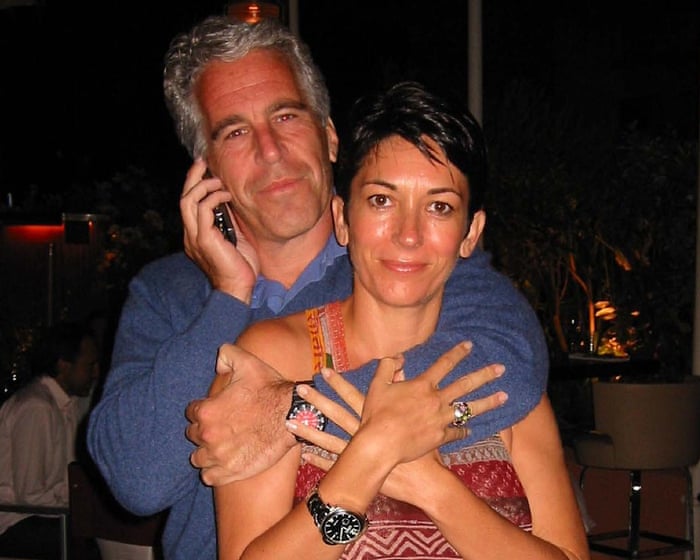

By that time, Saldaya had become the leading influencer in the freebirth community. A photo of her, partially nude and wearing a crown in a meadow, became a central part of FBS’s marketing. “I definitely think I own freebirth,” she texted another freelance employee.

Saldaya led a movement that promised women the return of a sacred experience they felt had been taken from them. “We are truly disrupting over a hundred years of obstetric violence,” she announced in a promotional YouTube video, calling herself a “pioneer of the birth liberation movement.”

FBS received numerous emails from women who had positive, unassisted births. Many had previously endured traumatic hospital deliveries. For example, the OB-GYN who delivered writer and birth worker Kaitlin Pearl Coghill’s second child in 2015 performed a membrane sweep without her consent. He later lost his medical license for having a sexual relationship with a patient. “He was a creep,” says Coghill, 36, from southern California, “and he was abusive—it definitely felt like sexual assault.”

After discovering FBS in 2020, Coghill freebirthed her third child in a joyful four-hour labor. “It changed my life,” she says. “I’d never felt so much power in my body.”

Soo Downe, a British midwife and professor at the University of Lancashire, notes that freebirthing, while still uncommon, seems to be increasing worldwide as women lose faith in professional maternity care. This trend is especially pronounced in the U.S., which has one of the highest maternal mortality rates among wealthy nations. Experts cite several reasons: limited access to midwife-led care, an overly interventionist approach fueled by fear of lawsuits, and a profit-driven healthcare system. The absence of universal healthcare also means some women must pay out-of-pocket for home birth midwives.

Birth in the U.S. is more medicalized than in other developed countries with strong midwifery traditions. “I’ve seen episiotomies performed without consent,” says Ivy Joeva, a doula from Ventura. “There’s a doctor in LA nicknamed ‘the butcher’ because she performs C-sections whether they’re needed or not.”

Hermine Hayes-Klein, an Oregon attorney specializing in maternity law, speaks with mothers who feel suicidal after giving birth. “Many women who choose unassisted birth do so because of horrific trauma from their first delivery,” she explains. “They experienced non-consensual procedures, were injured—sometimes severely—and fear it will happen again in a hospital.”

For these women, FBS offered an alternative. Launched in 2017, just before Instagram hit one billion users, FBS and Saldaya were among the first to leverage social media’s power, captivating women with images of mothers peacefully holding babies they had freebirthed at home. Women then binge-listened to the podcast, where Saldaya typically interviewed guests about traumatic births they felt were “sabotaged” by doctors and midwives. Saldaya expressed fierce anger…She spoke about the abuse she had witnessed: infants dying from drug overdoses, women sexually assaulted by doctors, and midwives who vowed to protect their clients but ended up betraying them. What’s astonishing is that no one forced me into it; I was brainwashing myself.

Her guests, many of whom discovered freebirth through her podcast, shared their birth stories. These were often epic tales spanning several days, where women were pushed to their physical and mental limits before emerging victorious, shedding self-doubt like old skin and embracing a new, heroic identity as freebirthing mothers.

Saldaya and Norris-Clark assured their followers that they too could experience the euphoria of unassisted birth if they let go of their reliance on a medical system that often mishandles women’s health. This message struck a chord with thoughtful, health-conscious women who were critical of modern trends—such as dependence on pharmaceuticals and junk food, or what they saw as an overreaction to the Covid pandemic—and were willing to make tough choices for their families’ well-being. Instead of trusting a flawed system, they would trust themselves. According to FBS teachings, if a healthy mother goes into labor, she and her baby will come out healthy. Together, Saldaya and Norris-Clark developed a freebirth approach that framed most birth complications as simply “variations of normal.”

In videos, they argued that freebirthing was not only safe but safer than medically assisted births. They declared that prolonged rupture of membranes, breech babies, week-long labors, and gestational diabetes could all be normal variations and usually nothing for freebirthing mothers to worry about, despite experts noting these conditions increase risks to both mother and baby. The pair also made false or dangerous claims about issues like hemorrhage, shoulder dystocia, retained placenta, and infant resuscitation.

At times, Norris-Clark and Saldaya were careful to include disclaimers, emphasizing that they weren’t qualified medical professionals and were only sharing personal experiences. They acknowledged that life-threatening situations could occur but presented them as rare, stating it was a woman’s choice how to give birth and whether to go to a hospital. However, their confident and credible tone led many women to trust advice that later proved medically unsound.

For example, in the Lighthouse forum in August 2022, a mother posted about her premature baby, born just two days before 36 weeks, who had needed an hour of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation and was still struggling to breathe. A medical professional would likely have urged immediate hospital care or calling 911. In her response, Saldaya noted she wasn’t present but said, “All sounds totally normal… shallow breaths and gurgling wouldn’t personally concern me.”

The mother detailed that the baby was only three hours old, had shallow breaths and gurgling, hadn’t urinated yet, passed meconium at birth, and hadn’t been able to nurse due to breathing difficulties, reiterating the hour-long resuscitation effort. Saldaya advised uninterrupted skin-to-skin contact with the mother in a dark room, suggesting it was all normal while acknowledging she wasn’t there to assess the situation.Shallow breathing and gurgling wouldn’t worry me personally. She needs to be on your bare chest to follow her natural nursing instincts.

When Nicole Garrison, a 34-year-old artist from New Jersey, became pregnant that same year, she imagined giving birth at a birth center or possibly at home with a midwife. She started searching online and discovered Free Birth Society (FBS). “As soon as I heard Emilee talking,” Garrison recalls, “I thought, oh my goodness, this is my tribe.” She listened to about 30 podcasts, often taking notes.

Sitting cross-legged on the floor of her spotless cottage, Garrison flips through the journals she kept back then. “I can literally feel my stomach churning reading this,” she says in her deep, soft voice.

On February 4, 2023, after listening to an FBS podcast, she wrote: “Processing fears. What would happen if my baby died? What would happen if I died? … I would take full responsibility.” On April 4, 2023, she added: “Radical responsibility is the way … for the safety of me and baby.”

Radical responsibility is the closest thing FBS has to a core belief. Saldaya borrowed the term from a self-help book for CEOs and business leaders called The 15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership. In FBS, taking radical responsibility means a freebirthing mother accepts complete accountability for all outcomes of her birth, including her own death or her child’s. No one is coming to rescue her, nor does she want them to. She is fully independent or, in FBS language, sovereign.

“What’s crazy,” Garrison says, “is no one had a gun to my head. I was doing the brainwashing myself.”

Her water broke on July 3, 2023. Seven days later, her daughter was born “pink and perfect,” but Garrison started hemorrhaging. Her partner at the time called an ambulance, but she sent it away because FBS teaches that hemorrhage “is almost unheard of” in a freebirth. In reality, while severe bleeding is rare, without medical care, a woman can bleed to death in just 15 minutes.

After the paramedics left, Garrison passed out. When she woke up, she was choking on her vomit. “I came back from a place of complete darkness, separation from everyone, even from God. I know I was dying.” Her partner called 911 again. At the hospital, doctors gave her a blood transfusion and removed her placenta.

Garrison had lied to her family about her plans for a freebirth. In the hospital, seeing the devastation on their faces, she began to realize “something is wrong with the women running these programs. That house of cards I had built came tumbling down.”

Like many businesses and ideologies that thrive on social media, FBS promotes a polished image of what it offers. Saldaya never features podcast guests who regret their decision to freebirth. She also routinely deletes negative comments on Instagram, such as one from earlier this year by a mother who lost her daughter: “My baby died at 41 weeks, stillborn, after I followed your teachings, and I will regret it for the rest of my life.” (That mother was also blocked.)

The first woman known to have lost her baby after following Saldaya’s advice was Lorren Holliday. When she became pregnant in 2018, she interviewed midwives but couldn’t afford the $5,000 down payment for their services. Reluctantly, she settled on the hospital until, one day while scrolling through Instagram, she found FBS: “What they offered was exactly what I was looking for.” Holliday, a friendly animal lover with short pink hair, lives in a trailer on an acre of land in the Arizona desert with her husband, Chris, their three barefoot children, and 35 dogs, cats, ducks, goats, chickens, and turkeys. “I wanted health. I wanted natural.”

She began binge-listening to the podcast and joined Saldaya’s FBS Facebook group. Holliday believed a freebirth would give herA gentle start to life for a baby. On October 1, 2018, Holliday, who was 41 weeks pregnant, began having contractions in her Airstream caravan. By the third day, she noticed the contractions were no longer spaced out but felt like one continuous contraction. She reached out to Saldaya for guidance, expressing on October 4 that the pain was unbearable and she was unsure if she was making progress. Holliday mentioned vomiting and described a contraction pattern that would have concerned a healthcare provider. Saldaya dismissed the idea of unbearable pain, calling it a dead end or a path to a hospital birth, and encouraged Holliday to endure and let go of her fears.

Holliday, who valued health and a natural birth, shared with her family in a photo caption her desire for wellness. Over the next two days, she reported severe swelling, excruciating pain, and discolored, foul-smelling amniotic fluid to Saldaya—potential signs of infection. She even sent a photo that might have shown meconium, a baby’s first stool, which in a hospital setting would prompt fetal monitoring due to risks like respiratory distress. Saldaya dismissed these concerns, insisting everything looked fine and urging Holliday to continue.

Meanwhile, Holliday posted in a Facebook group where midwife Ranee LaPointe advised her to go to the hospital, but such comments were quickly removed by administrators for violating group rules. After six days of active labor—far longer than typical in medical care—Holliday sent Saldaya a photo of bright green meconium. The next day, she reported reduced baby movement and an inability to urinate for 24 hours. Saldaya then suggested going to the hospital but advised lying about when her water broke to avoid an immediate C-section, providing a script to deceive doctors.

At the hospital, Holliday discovered her daughter had died. The baby, named Journey Moon, had dark hair like her father, and Holliday imagines her eyes were blue. Following the loss, a news report covered the case, and at Saldaya’s urging, Holliday lied to the journalist, denying she had received advice during labor. Both women faced backlash after the article, with Holliday defending her choice for a freebirth as an effort to give her daughter the best start, despite accusations of selfishness.

In a poignant image, Holliday is shown holding the ashes of her lost baby.Emilee Saldaya shut down the Facebook group and introduced a paid membership, boasting that moving behind a paywall actually boosted the business by allowing her to collect fees. “We’ve been rocking ever since,” she wrote in a 2023 post on Lighthouse.

Saldaya has consistently denied any involvement in Journey Moon’s death. “The story ended up saying I was her virtual midwife,” she later told students, “which isn’t true. We never worked together. I didn’t know this woman at all.”

When she moved to LA as a 17-year-old high school dropout, Emilee Saldaya was lively and fun-loving, with a strong personality that contrasted with her small frame. Born Emily Benner in Florida, she inherited an interest in childbirth from her mother, an obstetrician-gynecologist nurse, and entrepreneurial drive from her father, who sold medical equipment to hospitals.

In LA, Saldaya worked various jobs: infant massage therapist, waitress, trimming marijuana for cash, hula-hoop performer, and in a home birth midwife’s office. Friends remember her ambition to become wealthy. “She wanted to have a big voice and be an activist,” one said, “but she was also focused on making money.”

Starting in 2010, Saldaya worked as a doula, offering emotional and practical—but not medical—support to women during childbirth. She later said she was “haunted” by traumatic hospital births she witnessed, many of which she viewed as sexual assaults.

At the time, a committed feminist, Saldaya joined the non-profit LA Doula Project, providing free doula services to low-income women. There, she met fellow doula Laura Garland, who recalled, “She would do anything for her clients. She was very protective, a fighter.” But Garland also noted that Saldaya tended to exaggerate the number of births she’d attended, sometimes sharing other doulas’ stories as if they were her own.

Saldaya had hoped to train as a midwife but came to believe licensed midwives were part of the problem, accusing them of promising hands-off births only to “sabotage” them by transferring women to hospitals unnecessarily. She became enamored with unassisted birth and quickly planned a business to promote freebirth, including a podcast, courses, online schools, retreats, and even a festival.

On May 1, 2017, the podcast launched and was a hit, with 10,000 downloads in three months. However, there was an issue: Saldaya had never experienced a freebirth herself. She began thinking about how to legitimize her growing venture. Garland recalled her saying, “There’s this woman in Canada who is amazing. I’m obsessed with her, and I’m going to make her my best friend.” In New Brunswick, Yolande Norris-Clark was about to receive a life-changing phone call.

Saldaya’s call came at an opportune time. Norris-Clark had just reluctantly taken a marketing job and enrolled her older children in school, ending what she called her “wild days” of homeschooling, making art, baking, and walking barefoot in the woods.

Born Yolande Norris into an upper-middle-class family in Vancouver’s affluent Point Grey suburb, medicine was in her family too. Her grandfather, Professor John MacKenzie Norris, was a medical historian renowned as a world expert on the history of infectious diseases like cholera and plague.

In her early twenties, she had two children with her first husband, both delivered at home by famed underground midwife Gloria Lemay, who inspired her interest in childbirth. Lemay is currently awaiting trial for manslaughter after a baby died following a birth she attended in 2024. (Lemay has denied the charge.)

In 2005, at age 24, Norris separated from her husband, leaving her young sons with him. She later met and married Lee Clark, a ceramic artist. By the time she connected with Saldaya in 2017, Norris-Clark had become a Canadian social media influencer.Yolande Clark, featured on the Unpacking Ultrasound podcast, had seven children, with five born through freebirth at home. She is currently expecting her 11th child.

If Saldaya was seeking credibility in freebirthing, Norris-Clark had plenty to offer. At that time, Norris-Clark was a well-known figure online in the birth community, thanks to her popular blog and a viral 2012 YouTube video of her son’s freebirth.

In a 2022 podcast, Saldaya later told Norris-Clark, “I figured out how to make myself valuable to you… by making us a bunch of money.” In exchange, Norris-Clark would contribute her experience as an “authentic midwife.”

However, Norris-Clark was not a midwife. Lily Smallwood, a 40-year-old nurse from Fredericton and former friend, stated, “We were never midwives. We did not have skills.” Smallwood and Norris-Clark connected around 2013 due to their proximity and shared experience of freebirthing their children. They began attending local births together, with Smallwood assisting Norris-Clark, whom she believed had more expertise because Norris-Clark had taken a doula training course under Lemay in Vancouver.

Norris-Clark was careful not to market herself as a midwife, instead calling herself a traditional birth attendant and charging up to $3,000 per birth—significantly more than a doula would typically earn. (Smallwood occasionally received gifts equivalent to a doula’s fee.)

In one video call, Saldaya warned her students, “You will interact with babies not making it. People turn real fast.”

When Saldaya and Norris-Clark connected in 2017, Norris-Clark claimed on her blog to have been “present at hundreds of births.” Smallwood expressed skepticism, saying, “I’d be floored if there were hundreds,” noting that the unassisted birth scene in New Brunswick was “very underground, very quiet.” She estimated Norris-Clark attended between 12 and 20 births from 2013 to 2016.

Although Norris-Clark found it ironic that Saldaya started a business promoting freebirth without having experienced it herself, the timing was favorable. Norris-Clark agreed to share transcripts for a book she had been working on, which became “The Complete Guide to Freebirth.” To date, the book has earned over $5 million.

In January 2018, Saldaya attempted her first freebirth. With support from her sister, a nurse friend training to be a nurse-midwife, and her husband Johnny, who worked in the cannabis industry, she labored at home for 50 hours. She then went to the hospital for a procedure to reposition her cervical lip before returning home to give birth to her daughter. Privately, friends said she was shaken by the experience, as transferring to the hospital meant it wasn’t a true freebirth. Publicly, however, she celebrated it as a success, later calling it “epic” in a podcast.

By 2020, Saldaya and Norris-Clark had built a profitable partnership. Norris-Clark was the charismatic, intellectual partner, using her photogenic family to appeal to exhausted mothers on social media by portraying her births as pain-free and orgasmic, and herself as never overwhelmed by her large family. In contrast, Saldaya was more abrasive but highly focused on expanding the business, unlike Norris-Clark, who could seem scattered.

Friends noted that Saldaya often adopted Norris-Clark’s ideological stances. When Norris-Clark rejected the concept of gravity, Saldaya declared she was no longer committed to a round Earth. When Norris-Clark dismissed germ theory, Saldaya told friends she stopped washing her hands. And when Norris-Clark renounced feminism and expressed a desire to submit to her husband, Saldaya quietly removed the “radical feminist” label from their podcast marketing.

After…Norris-Clark shifted to the right politically, and Saldaya followed her lead. She started promoting “wild pregnancy,” a term Norris-Clark created to describe pregnancy without prenatal care, and German New Medicine, which Norris-Clark supports and which argues that illnesses stem from unresolved emotional conflicts rather than germs.

Together, they developed a rigid approach that clashed with the broader unassisted birth community, where people often go to medical appointments, get ultrasounds to inform their decisions, and prepare for emergencies. For example, when Coghill had an unassisted birth in 2020, she gave her husband a folder with instructions on what to do if problems arose.

In contrast, FBS taught that even thinking about a backup plan showed a lack of faith, because a truly independent woman should trust birth completely. “You have to pick one world or the other,” Norris-Clark said in a video call with followers. “If you’re setting up a medical team nearby, you’re not getting the best of both worlds—you’re choosing the medical world.”

As her influence grew, Saldaya looked for ways to make money from a practice that is inherently free. She knew not all women following FBS were prepared to give birth alone, but in most places, working as a midwife without a license was illegal. “To get around these unfair laws, I came up with the term ‘radical birth keeper’… to be clear, a radical birth keeper is essentially a genuine midwife,” she told her followers. In 2020, she trademarked “Radical Birth Keepers,” with the registration stating it offered education and coaching in “midwifery.”

The first Radical Birth Keeper (RBK) school opened in 2020 and, despite costing $6,000, filled up quickly. Over the next five years, it trained over 850 “authentic midwives” from around the world. In 2024, Saldaya and Norris-Clark took it further by launching the MatriBirth Midwifery Institute (MMI), a $12,000, year-long “gold-standard online intensive midwifery school.”

In reality, certified American midwives spend years learning from experienced mentors, training to handle life-threatening birth complications. Most carry medication to stop bleeding, know how to assist with delivering the placenta, and are trained in reviving newborns.

FBS students, however, learned through an online Zoom course. The RBK school lasted only three months, with much of the content focused on building a business, marketing, and finding clients online. While Norris-Clark and Saldaya admitted that some emergencies might require a hospital transfer, they generally downplayed these risks and taught students not to act as “heroes” to keep clients safe. Instead, the mother was to take full responsibility for her birth, even if it meant facing death. Some women paid FBS-trained Radical Birth Keepers between $3,000 and $5,000—similar to what licensed midwives charge—without realizing these helpers lacked life-saving skills until it was too late. They thought they were hiring real midwives.

To avoid legal trouble, Saldaya and Norris-Clark instructed their students to only accept cash gifts after a successful birth, never sign contracts, and avoid clients who might blame them if something went wrong. “You will encounter babies who don’t survive birth,” Saldaya warned in a video call, adding, “People turn on you quickly.” She told RBKs to use fake names if they went to the hospital with clients and to act like a “sweet, innocent neighbor” if police were called after a baby’s death.

When 42-year-old Keelee Sullivan from California enrolled in the RBK school in 2023, she borrowed $6,000 from a relative, believing it was for “midwifery school.” After the first bi-After a birth she attended resulted in a hospital visit, Sullivan realized she had been practicing “delusional optimism” and was “not educated or prepared” to be a midwife. She stated, “And no, I am not willing to go to jail.” She has not attended any births since.

Saldaya and Norris-Clark always maintained that being a Radical Birth Keeper is not illegal. “You are not practicing medicine,” Saldaya told her students. However, in private, Norris-Clark ridiculed medical disclaimers. During a call with students, she laughed, “Always consult your licensed certified medical professional. This is for entertainment, informational, artistic purposes only. Yeah, it’s all just performance art, right?”

Molly Flam, a 34-year-old doula from Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, who attended MMI—FBS’s flagship midwifery school—described it as “a scam.” She paid $9,000 only to find the pre-recorded videos were rambling, unprofessional, and contained inaccurate and confusing medical advice. “They’re showing up to classes disheveled, talking about their personal lives,” Flam said. “There was no structure.”

From 2020 to 2025, FBS operated nine RBK schools and at least one MMI school, generating over $4 million in sales. At one point in 2024, the organization was making up to $160,000 per month, according to a former employee.

As money flowed in, Saldaya established what she called her “queendom.” She purchased three properties in Hayesville: a four-bedroom house on eight acres, an adjacent 53-acre plot, and a school on 17 acres. She spent tens of thousands renovating the school, only for it to fail a year later. She also bought over $10,000 worth of lawn ornaments, including giant toadstools, for the school and festival, acquired a Range Rover, and spent more than $100,000 on a swimming pool and outdoor kitchen in her backyard. During this time, a friend recalled Saldaya asking for advice on how to get a private jet.

Fulfilling her long-standing ambition to buy land and build a community, Saldaya invited around 13 families to move to Hayesville. Some worked for FBS and lived in yurts on her property. By 2023, many high-profile employees had fallen out with her, leading insiders to refer to them as her “fallen soldiers.”

Serendipiti Day, who had seen Saldaya wear a crown in the meadow in 2021, was one of those employees who became disillusioned with FBS. She discovered the group after attending underground births in her community and paid $300 to become a member in 2020—a significant amount for Day, who was then an uninsured anarchist. Her intellect and radical feminism caught Saldaya’s attention, who asked her to lead Zoom calls and referred coaching clients to her. Soon, Day was earning more than she ever had before.

As FBS expanded its client base, it grew more extreme. Within the Lighthouse community, women learned that wild pregnancies were the ultimate goal. An unofficial hierarchy of birth emerged, with C-sections at the bottom and freebirth at the top. Saldaya suggested that women with unsupportive partners give birth in hotels and compared family members who opposed freebirth to homophobic parents. Anti-midwife rhetoric also intensified. In a call with Lighthouse members, Saldaya said of midwives, “You’re fingering women in birth. Go fuck yourself.”

Despite her financial success and public image as a women’s advocate, Saldaya privately grew weary of her community. When an Instagram follower questioned why Lighthouse membership cost $500, Saldaya vented to a freelance employee via text: “That idiot bitch asked me where the money went. Where does the money from your job go?”

When women’s births did not go as planned, Norris-Clark and Saldaya offered paid sessions to…Let’s examine what went wrong. Neither woman had any training in grief or trauma counseling. On May 20, 2024, Camille Voitot joined a Zoom call with Norris-Clark from her home in Frontignan, southern France. Voitot was barely functioning. Two weeks earlier, her son Marlow had died during a freebirth.

Voitot, a 35-year-old therapist, discovered FBS while researching birth options when she and her wife, Jo, began fertility treatment in February 2023. Voitot has always been someone who does her own research rather than simply accepting what others tell her. “I wanted a natural birth,” Voitot explains in their home just meters from the beach, an inviting space filled with plants and art. “I wanted my body and my baby to be respected.”

Throughout 2023, Voitot listened to the FBS podcast daily. She came to view Saldaya and Norris-Clark as the big sisters she never had. Growing up without a close relationship with her mother, she craved the kind of wisdom that traditionally would have been passed down by elder women in her community.

When she became pregnant in August, Voitot learned that home birth wasn’t covered by state insurance, meaning she’d have to pay €900 for a midwife, which felt unfair. After purchasing The Complete Guide to Freebirth and Norris-Clark’s book, she decided to proceed with freebirth.

Jo had concerns but told Voitot it was her choice. She knew Voitot had previously struggled with feelings of shame and trauma related to her sexuality and wanted to support her. Friends were also worried—they later told Voitot they “didn’t recognize” her. But by then, Voitot believed freebirth was “the safest way to give birth” without the risk of “obstetric violence” in a hospital.

After Marlow died, Voitot felt an overwhelming need to speak with Saldaya and Norris-Clark. She couldn’t afford Saldaya’s $350 fee for an hour-long call, but Norris-Clark agreed to a reduced rate of $150.

During this call, Norris-Clark told Voitot that her son’s death wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. “There’s an overall assumption that death is the wrong outcome,” she said. “And I don’t think that can really ever be true.”

At the time, Voitot didn’t fully grasp what Norris-Clark was saying. “I was so amazed by the fact that I could speak to her directly that I didn’t really hear what she said.”

As months passed after Marlow’s death, Voitot began to question things. Why had she never heard stories on the podcast from mothers who lost babies during freebirths and now regretted it? Why had she believed “you can only have a positive outcome”?

She reached out to Norris-Clark for a second debrief. This time it cost $800.

The two women spoke on September 29, 2025. The call quickly became tense and difficult. Voitot asked Norris-Clark how she could have said that death wasn’t necessarily a bad outcome.

“This idea of death being bad is not really something I believe is true,” Norris-Clark said. “But that doesn’t mean I think it’s not a big deal.” She acknowledged she’d never lost a newborn baby herself. “It’s a terrible thing, yeah,” she said. “And also, not ‘bad,’ you know?”

They circled around a question that had been on Voitot’s mind for the past year: Did Norris-Clark take any responsibility for influencing her decision to freebirth?

Norris-Clark seemed irritable but remained civil. Her answer was no. “People are responsible for their own decisions and their actions. You could have read other books. You could have gone on other websites. I am so sorry about your experience, Camille, but you are a woman that I don’t know, who lives in France.”

By 2024, it was becoming…It is becoming increasingly difficult to ignore the number of babies dying to mothers following the Free Birth Society (FBS) approach. These deaths followed a pattern: first-time mothers, whose pregnancies are already higher-risk, attempted freebirths lasting several days or even a week after prolonged pregnancies. Some women went beyond 44 weeks of pregnancy.

While most freebirths result in positive outcomes and pose low risks for healthy mothers, the radical version promoted by Saldaya and Norris-Clark raised concerns even among freebirth advocates.

The most alarming aspect was FBS guidance on resuscitating newborns. Their courses offered basic emergency advice, though experts found it flawed. Saldaya and Norris-Clark also argued that resuscitation was often unnecessary, claiming it deprived babies of the choice to start their lives. Norris-Clark referred to it as “meddling” and “sabotage” in her book. In a 2024 podcast, Saldaya stated that babies “need to learn how to breathe on their own” and reflected on the significance of a baby “claiming their breath.”

They taught that if an FBS-trained birth keeper was present, only the mother should decide whether and how to help a non-breathing infant. Saldaya emphasized in a 2024 podcast, “I would never resuscitate a baby. That’s cuckoo bananas to me.”

Watching this is like seeing a parent do nothing while their child drowns quietly in a pool.

In 2025, Saldaya described attending a birth where the baby didn’t breathe for “a couple of minutes.” She admitted it was challenging because she had to unlearn her conditioning “to want to hear the baby breathe.” Despite her discomfort, she did nothing, stating, “There’s nothing for me to do. I’m not going to resuscitate someone else’s baby or make calls for them.”

Exhausted mothers may not recognize respiratory distress in their babies until it’s too late, or their judgment may be clouded by FBS teachings. Just minutes without oxygen can be fatal, and survivors may suffer lifelong brain injuries, as in the case of Esau Lopez. Milder effects might not show for months or years.

Saldaya told her students that if parents choose not to seek medical help, it’s their decision, and for some, “giving birth to a severely compromised baby at home and allowing that baby to die with dignity in the arms of their family is a reasonable outcome.”

Allowing a child to die raises legal issues. Professor Warren Binford, a children’s rights expert, explains that parents are legally required to seek medical care for a struggling newborn. Failure to do so can lead to charges of manslaughter, homicide, or murder, and the same applies to anyone present who doesn’t seek help.

Saldaya and Norris-Clark followed their own advice. In 2019, Norris-Clark freebirthed her eighth child, who was born “limp, unmoving, and grayish white.” She waited without intervening, believing it would deprive him of “his ownership over his vital experience.” In 2022, Saldaya shared a video of her second child’s freebirth online, showing her son limp and in respiratory distress for over four minutes without her calling 911 or resuscitating him.

Experts who recently…A medical expert who reviewed the video described it as depicting a life-threatening situation, stating that a healthcare provider would have started resuscitation within 60 seconds. Professor Michelle Telfer, an associate professor of midwifery at Yale, commented, “Watching this video is difficult. It’s like watching a parent sit by the pool while their child is quietly drowning and they do nothing.”

Saldaya and Norris-Clark appeared on a Free Birth Society podcast. Both of their children survived. However, Saldaya, who taught her followers to always have a “death plan,” had thought about what she would tell authorities if one of her children died after birth. She planned to claim the baby was stillborn. “I would certainly lie,” Saldaya told her students in 2023. “If my baby was born alive, then died, and then I involved the police—that baby was born dead.”

Saldaya also instructed her students not to immediately call 911 if a child died during a freebirth, saying, “Dead is dead.” If grieving families chose to illegally bury their children on their property, she shared advice from an underground midwife: “Dig a little deeper.”

After working closely with Saldaya for two years, Day left what she referred to as a “death cult” in 2023.

By conventional standards, FBS is not a cult. However, former members often use terms associated with high-control groups to describe the influence they felt the organization had over them, leading them to act in ways they now struggle to comprehend.

It is difficult to determine exactly how many babies have died in FBS circles, as many “loss moms,” as they are known, withdraw after their tragedies and rarely respond to media inquiries.

Within the Lighthouse community alone, approximately eight women appear to have experienced stillbirths or neonatal deaths in the past year, out of a group of about 600 women, many of whom were not pregnant.

Why did no one encourage this woman to seek medical attention immediately, despite the clear emergency?

As part of this Guardian investigation, we conducted in-depth interviews with 18 mothers who suffered late-term stillbirths, neonatal deaths, or other serious incidents after they or their birth attendants were heavily influenced by FBS. Their stories were verified through interviews with friends, family, and partners, and supported by journal entries, medical records, videos, message threads, or legal documents. In all 18 cases, evidence suggests FBS played a significant role in the decision-making that led to potentially avoidable tragedies.

These include Adair Arbor, who would never have considered an unassisted birth before encountering FBS. Her daughter, Ilex, was stillborn in January 2021 after a 115-hour labor. Amalia Hernandez nearly bled to death in March 2024 after refusing to call an ambulance, believing her postpartum bleeding would resolve on its own. That same year, Haley Bordeaux went blind and suffered multiple strokes following a four-day labor during which she was in contact with Saldaya via phone calls and texts through a friend. When Saldaya was later told that doctors attributed Bordeaux’s temporary vision loss to severe pre-eclampsia, she responded, “She doesn’t have severe pre-eclampsia, that’s so entirely ridiculous.”

We identified an additional 30 cases, almost all involving late-term stillbirths or neonatal deaths, where mothers appeared to have been influenced by FBS, based on reporter interviews, Lighthouse or social media posts, or podcast appearances. Most of these incidents occurred in the US and Canada, but also included births in Switzerland, France, South Africa, Thailand, India, Australia, the UK, and Israel.

“There’s this cycle,” says one former Lighthouse member whose baby was stillborn in 2024. “Children…”Children die. The community knows about it for a while, but then new members join the Lighthouse, and they are forgotten. It feels like our children are being erased.

In December 2024, Norris-Clark appeared on a video call from a hotel room, looking frantic. She told students at the Matribirth Midwifery Institute that she had become an “international fugitive” after a freebirth she attended in Nicaragua went wrong. The mother was unable to deliver her placenta, began bleeding heavily, and then had a seizure. Paramedics were called. Norris-Clark said that afterward, “there was swearing and screaming and people threatening me.” She fled the country briefly, stating she would no longer assist at births because she did not want to go to jail.

When Norris-Clark launched the flagship MMI program with Saldaya in September 2024, she told her students she was “fulfilling one of the central purposes of my life by teaching midwifery.” Just three months later, she made this U-turn.

One of Norris-Clark’s MMI students was a 23-year-old pregnant first-time mother from Australia. She was having a wild pregnancy with no prenatal care. On March 5, 2025, she posted in the Lighthouse that she had been in labor for five days and was “exhausted and hitting a wall of confusion.” Saldaya responded, “Sounds so normal and so hard. Baby is coming. You can do it.”

On day eight, the mother posted “still going”; on day nine, she wrote that her “belly is taking on a strange shape as I contract, sort of like 2 bulges.” She was describing a Bandl’s ring, a sign of obstructed labor and a medical emergency. Yet no one advised her to go to the hospital.

Later, the mother posted a video of her son. He was grunting, struggling to breathe, and his chest was retracting with effort. “Hey y’all,” she wrote, “just wondering if this sounds normal for a sleeping newborn?” Members expressed concern, but still, no one told her to call emergency services immediately.

“With a broken heart,” the mother later posted, “I want to share that baby boy didn’t make it.”

It was this video of a dying baby that finally sparked widespread shock and revulsion in the FBS community. Days later, on March 16, 2025, a Reddit community called r/FreebirthSocietyScam was formed to “help deprogram from the mind control, culty atmosphere and rigid dogma of FBS.”

On March 27, an MMI student posted in a private chat for fellow students, asking, “I would like to know why it has not been addressed that a woman in this space, in our current cohort, lost her baby… no one encouraged her to seek medical attention ASAP, even though it was clearly a medical emergency.”

Saldaya deleted her post and then removed her from the course. Over the following weeks, 13 students either left or were expelled from MMI.

Saldaya and Norris-Clark seemed concerned about the legal implications of their actions. In May, FBS posted a disclaimer on Instagram, stating that its content was for “educational and informational” purposes only and not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any medical condition related to pregnancy or birth. It advised, “For medical advice, consult your healthcare provider.” In a call with her remaining students after the Reddit community formed, Saldaya admitted, “[We] overplayed our hand, calling this a midwifery school.”

FBS did not respond to requests for comment. However, in recent months, Saldaya and Norris-Clark have shifted to describing themselves as online educators training “birth mentors,” and MMI has been renamed the MatriBirth Mentor Institute. There are indications that the business partners may be separating: Norris-Clark was recently removed from the FBS website homepage, which has been redesigned to feature Saldaya prominently.On Instagram, Norris-Clark has referred to critics of FBS as “pathetic losers,” defending her partnership with Saldaya as “the most ethical kind of business you can run.”

In a statement on her Instagram account, Saldaya rejected being portrayed as “some manipulative cult leader” and likened the negative attention to “advertising” that “has brought me a wave of new followers.”

“Let me be clear: I don’t care if you freebirth,” she said. “I don’t encourage strangers on the internet to do anything at all. You are an adult. You have big decisions to make. It’s important to know freebirth is an option; what you choose is up to you… I speak from my own truth, based on a lifetime of dedication to understanding birth and the toxic power dynamics of the industrial birth system,” she added. “I stand firmly by my values. In a world where mothers and babies are often mistreated during birth, I will always wholeheartedly support women finding their own path. And yes—it turns out many of them prefer to give birth at home, just like I do.”

In a call with her students, Saldaya described the Reddit community as “a little troll group.” On August 8th, in her ninth month of a wild pregnancy with her third child, she released a podcast with Norris-Clark discussing the backlash. Norris-Clark called their critics “a bunch of very deeply insecure, bitter, sad, lonely women.” Saldaya laughed and compared them to the fish that eat dead skin during a pedicure, shuddering and saying, “Disgusting.”

A week after the podcast aired, Saldaya stopped sharing personal updates on social media. Ex-FBS members, aware her baby was due, grew concerned, but she remained silent. Then, on August 25th, she posted an announcement.

“I recently gave birth to a beautiful baby, stillborn at 41 weeks of gestation. Our son, our baby, was not born alive.”

There were 15 pregnant teachers and students in the first-ever MMI school. Saldaya’s loss brought the number of full-term stillbirths or neonatal deaths in this group to three, all occurring within a six-month period.

Last month, Norris-Clark flew to visit Saldaya in North Carolina. Afterward, she participated in a birth trauma debrief with a mother who had lost her child. When Saldaya’s recent loss was mentioned, Norris-Clark said, “She’s integrating this experience beautifully,” adding, “She’s so grateful that she chose freebirth, especially for her son.”

To listen to The Birth Keepers podcast series, subscribe to The Guardian Investigates feed, and it will be available automatically when it launches in December. Additional reporting by Elizabeth Cassin, Olivia Lee, Joshua Kelly, Lucy Hough, Tom Wall, Joseph Smith, Philip McMahon.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about influencers promoting natural home births and the associated risks written in a clear and natural tone

Basic Understanding Definitions

1 What is a free birth

A free birth is when a person intentionally gives birth at home without any medical professional present such as a midwife or doctor

2 Whats the difference between a home birth and a free birth

A planned home birth is typically attended by a licensed midwife who brings medical equipment and training A free birth has no trained professional in attendance

3 Who is the Free Birth Society

Its an online community and resource hub popularized by influencers that advocates for and provides information on free birthing It has been linked to several cases where things went wrong

4 How are influencers making money from this

They earn through social media ad revenue selling online courses ebooks and coaching programs on empowered or natural birth and through brand sponsorships

Motivations Perceived Benefits

5 Why would someone choose a free birth

Common reasons include a desire for total control over the experience a fear of medical interventions in hospitals past traumatic birth experiences or a belief that birth is a natural process that doesnt require medical oversight

6 What benefits do influencers claim free birth has

They often promote it as a more empowering intimate and spiritually fulfilling experience free from what they describe as unnecessary and stressful medical procedures

Risks Problems and Consequences

7 What are the main risks of free birthing

The biggest risk is that a sudden lifethreatening complication can arise for the parent or baby with no one present who can manage it This includes hemorrhage umbilical cord problems or the baby needing resuscitation

8 Is free birth illegal

In most places it is not illegal to give birth at home without assistance However the legal landscape can be complex especially if something goes wrong and negligence is suspected

9 How is the Free Birth Society connected to infant deaths

Investigations and news reports have linked the advice and community atmosphere of the Free Birth Society to specific cases where babies died during or shortly after free births Critics argue the group downplays risks and discourages seeking medical help even when clear danger signs appear