Fifteen years ago, Karl Ove Knausgård reflected on the success of his six-volume autofictional work My Struggle during a Norwegian radio interview, saying he felt as if he had “sold my soul to the devil.” The series had become a runaway hit in Norway—a success later mirrored worldwide—but it also sparked anger in some circles due to its depiction of friends and family. The work was an artistic achievement with a personal cost, giving it a Faustian quality in the author’s eyes.

This experience forms the foundation of Knausgård’s latest novel, The School of Night, the fourth book in his Morning Star series. Here, his signature character studies and meticulous attention to everyday details blend with a gripping supernatural plot involving a mysterious star in the sky and the dead returning to life. The first and third volumes, The Morning Star and The Third Realm, revolved around the same interconnected characters, while the second, The Wolves of Eternity, shifted to the 1980s to tell the story of a young Norwegian man discovering his Russian half-sister. Only near the end of its 800 pages did it connect with the events of The Morning Star. The School of Night moves backward again, this time to London in 1985, following a young Norwegian named Kristian Hadeland as he pursues his dream of becoming a famous photographer. Kristian proves willing to sacrifice anything and anyone for success, making his rise and fall a compelling and unsettling read.

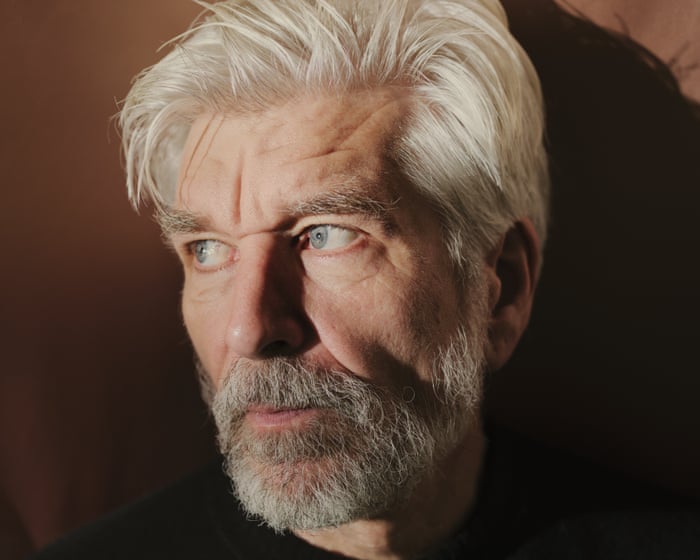

I met Knausgård on a beautiful autumn day in Deptford, southeast London, with the water lapping against the river wall below us. This neighborhood features prominently in The School of Night. When I asked if he had always known he would write a London novel after moving to the city nearly a decade ago, he replied, “I think I did. I was never here in the ’80s, but growing up I read NME and Sounds, and I listened almost exclusively to British music—some American bands, but it was really all about Britain. And then there was football. Every Saturday, British football. So I grew up as a true anglophile.” In his twenties, he spent a few months living with a Norwegian friend in Norwich. “It was like the most uncool place in Britain,” he said, laughing. “But it was still very cool to me.”

In 2018, Knausgård moved from Sweden to London to be with his fiancée, now his third wife, who had previously been his editor. They have a son together, and his four children from a previous marriage split their time between him and his ex-wife. He describes life in London as similar to his life in Sweden: “It’s the writer’s life. I’m at home writing, with my family—my kids and my wife. But then there’s London outside.” When he’s not writing, he enjoys browsing records at Rough Trade, attending concerts, and watching football matches. “I really love it here,” he says.

Knausgård chose Deptford as Kristian’s home because of its connection to Christopher Marlowe, one of the most prominent authors of the Faust legend. He discovered Marlowe through a Borges essay that described “the blasphemy, the murder, the way he was killed, the ruthlessness, the wildness,” and he was instantly captivated. The School of Night takes its name from a group of late 16th-century writers and scientists, including Marlowe, George Chapman (the translator of Homer), and Sir Walter Raleigh, who were rumored to be atheists. The idea of the School of Night as a real clandestine group was proposed by Shakespeare scholar Arthur Acheson in the early 20th century, though the truth remains shrouded in mystery.This approach is entirely fitting for Knausgård’s novel, which is filled with strange occurrences and mysterious characters whose motives are unclear.

However, Marlowe’s version wasn’t Knausgård’s first introduction to the Faust legend. That came from Thomas Mann’s 1947 novel Doctor Faustus, which relocates the story to Wilhelmine and later Nazi Germany. Knausgård recalls, “I think I was 19 or 20, and I still remember one of the first scenes where Zeitblom, the book’s narrator, and Leverkühn are with Leverkühn’s father. He shows them natural wonders—things that aren’t alive but behave as if they are. That intersection between life and non-life, with art in between, has stayed with me ever since.” After our conversation, I looked up the passage and found its mix of vivid detail and philosophical reflection to be unmistakably Knausgårdian.

He mentions that he doesn’t really do research. This is somewhat reassuring, considering an episode in which Kristian repeatedly boils and tries to skin a dead cat for a photography project. Instead, Knausgård writes with what seems like remarkable freedom. He often says he discovers where a story is going as he writes, and that was true for The School of Night as well. “When I started writing, Kristian was just an ordinary guy with nothing unpleasant about him,” he explains. It was only when he wrote the section where Kristian visits his family that he realized the character had no empathy. “That’s always how I work,” Knausgård says. “I just write, and then something happens, and the consequences follow.”

The novel takes the form of a long suicide note written by Kristian after his fall from worldwide artistic fame. It is steeped in death and filled with reflections on life’s fleeting nature. Isolated in a cabin on a remote Norwegian island, Kristian observes that “death was the rule, life the exception.” On a train in London, he thinks that in a hundred years, everyone in the carriage will be dead. During a Christmas visit home, he compares human lives to the snow falling outside:

Humans descended like snow through the ages. There were billions of us, dancing this way and that until our flight ended abruptly and we settled on the ground. What happened then? Billions more came falling down, covering us. I was one of those snowflakes, still falling… and the enormous blizzard of the unborn, waiting to descend, would smother not only us but every trace of our lives, rendering them less than meaningless—nothing, zilch, nada. They would become snow in snow, darkness in darkness. And so would we.

I ask Knausgård if he sees art as a way to fight against this, to leave a mark against the darkness. After a long silence—he often pauses to think before answering—he says, “No, that’s not important at all. It’s more about perspective. If you take one step back and see life that way, everything is meaningless. Then you take a step in, and it’s completely full, brimming with meaning. I think that’s similar to writing a book: you immerse yourself in the present moment, and it becomes incredibly meaningful.”

This insight comes from his own experience: huge ambitions and belief, completely crushed, then getting up and trying again. It reflects the methods Knausgård uses—a unique blend of the epic, with multi-volume novels often over 500 pages, and the intimate, packed with everyday details.The text covers topics like changing diapers, making coffee, getting drunk, kissing, and the perfect texture of cornflakes. It highlights a difference between Knausgård and his character Kristian, who once mocks his mother by saying, “I can’t believe you’re actually talking about the weather.” She defends herself and Knausgård’s approach by replying, “Life is in the everyday, Kristian.”

In the novel’s early parts, Kristian’s daily life is mostly about failure. The School of Night effectively portrays the challenge of finding one’s creative path—that feeling of not measuring up artistically yet holding onto the faith to persist. This theme is something Knausgård delved into deeply in Some Rain Must Fall, the fifth volume of My Struggle, which recounts his time as a creative writing student in Bergen. “Yeah,” he says, “that’s basically taken straight from my experience trying to become a writer. All those grand ambitions and the belief that gets completely shattered, and then,” he laughs, “you get back up and try again.”

Knausgård grew up on the island of Tromøy in southern Norway until age 13, when his family moved to Kristiansand. His mother was a nurse, and his father a schoolteacher. His difficult relationship with his father, who later became an alcoholic and nearly a recluse, is vividly and painfully depicted in My Struggle. Initially, Knausgård went to university in Bergen aspiring to be a poet, but as described in Some Rain Must Fall, he was terrible at it. “You understand nothing about yourself and have no idea what you’re doing,” a classmate told him. Similarly, Kristian’s early work is repeatedly dismissed by his sister, his artist friend Hans, and a tutor at his art school.

Reflecting on that apprentice phase, Knausgård notes how painful it is because you don’t know if things will ever improve. “There’s so much you don’t know at that age when you want to pursue something, and the only way to learn is through experience. You don’t realize that failure is necessary, even though it hurts, but it’s the only path. Yet, you never know if you’ll keep failing—there are no guarantees.”

In some ways, Kristian allowed Knausgård to explore a darker version of himself. When the first volume of My Struggle was published in 2009, detailing the decline of Knausgård’s father and grandmother, his father’s family threatened legal action. Others also objected to their portrayals, leading Knausgård to adjust his approach in later volumes. In contrast, Kristian hardly considers others’ feelings or the ethics of his artistic choices.

Knausgård admits that while writing My Struggle, he knew “I was doing something I probably shouldn’t have done.” So how did he decide where to draw the line? “My own rule was that if it was too physically painful, I didn’t go there.” When asked if he felt physical pain, he replied, “Yeah, it was in my body. But when I wrote as Kristian, he doesn’t care. That freedom he finds in the end is, to me, the Faust story.”

In the book’s acknowledgments, Knausgård writes of his family: “Without their light, I would never have been able to withstand the darkness of this novel.” Was it hard to spend so much time in Kristian’s mindset? “It wasn’t pleasant because I didn’t find him outside myself—I drew him from within. I’m not like him, but I amplified certain parts of myself in him. That wasn’t fun at all, but it was interesting.”

The School of Night is KnaUsgård’s 21st book. He speaks very practically about his productivity, something he clearly shares with Kristian. “It doesn’t have to be many hours, but if you write every day, five days a week, you can finish a novel in a year.” His 22nd book, volume five in the Morning Star series, is titled Arendal and was published in Norway last autumn. When I suggest that the Morning Star series could continue indefinitely, he agrees: “I could keep extending it for the rest of my life, really.” But immediately after saying this, he clarifies with a determined tone that volume seven, which he’s about to start writing, “will be the last. I want to work on other things.”

This doesn’t mean his enthusiasm for the series has faded. Just the day before, he told me, he made the final edits to the manuscript for volume six, I Was Long Dead, which is due in Norwegian bookstores in a few weeks. It revisits Syvert and Alevtina from The Wolves of Eternity, and he says with a laugh that its climax involves “real blood spatter and chainsaw kind of action. It’s the wildest book I’ve ever written.” The School of Night, translated by Martin Aitken, is published by Harvill (£25). To support the Guardian, you can buy a copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about Karl Ove Knausgrds reflections on his work ambition and its consequences written in a natural and accessible tone

General Beginner Questions

1 What is Karl Ove Knausgrds My Struggle about

Its a sixvolume autobiographical novel where Knausgrd writes with extreme honesty about his own life including his relationships with his family his inner thoughts and his daily experiences

2 What does he mean by crossing a line

Hes referring to writing about real people in his life in a deeply personal and often unflattering way without their full consent He knew he was violating social and personal boundaries for the sake of his art

3 Why is his work so controversial

The main controversy comes from the fact that he used the real names and detailed private stories of his loved ones which caused them significant pain and public scrutiny

4 What were the consequences he faced

He severely damaged relationships with family members and friends Some family members were deeply hurt and publicly condemned the books and he faced a great deal of public criticism and media attention

Deeper Advanced Questions

5 What is the shadowy aspect of ambition he reflects on

He reflects on how his powerful ambition to create great literature forced him to sacrifice the wellbeing of the people closest to him He questions whether the artistic achievement was worth the human cost

6 How did his ambition affect his writing process

His ambition drove him to pursue absolute honesty at any cost This meant suppressing his guilt and empathy while writing to avoid selfcensorship which is a key reason he felt he was crossing a line

7 Is My Struggle considered fiction or nonfiction

Its a complex blend While its marketed as a novel and uses literary techniques the events and people are real This blurring of the line is a central part of its power and its ethical dilemma

8 Did Knausgrd regret writing the series