When one of my daughters turned 18, our relationship entered a crisis so painful it lasted longer than I knew how to bear. I was a psychotherapist, trained in child and adult development, yet I was completely lost. Decades have passed since then, but when I recently spoke to her about that time, a wave of distress washed over me as if it were yesterday.

This is how my daughter, now a mother herself, described that era when I asked her: “I was furious, desperate, and lonely. I fought with you and Dad in a way no one in the family ever had before. I remember screaming at you during a walk, while you desperately begged me to be quiet because people could hear. I wanted them to hear. I wanted to shatter this image of us as a happy family—and I was incredibly successful at it.”

I remembered looking at other families and wondering what they had done right that I had gotten so wrong. I didn’t know how to navigate our relationship now that she was technically an adult but still seemed so young and vulnerable to me. I was frightened for her, angry with her—an emotion I didn’t want to feel—and furious with myself. Underneath it all lay the shame: I had failed her and our family.

The shift from anxious manager to respectful witness is one of the hardest tasks of parenting adult children. Questions overwhelmed me: Why didn’t I see this coming? What did I do wrong? How could I fix it? I searched for guidance and found almost nothing. There was virtually no information to help me make sense of this new terrain. I wish I’d known what recent neuroscience research from Cambridge University suggests: that the brain’s adolescent phase extends until the age of 32. These findings, published in Nature Communications, challenge traditional assumptions that maturation ends at 18 or 25, and highlight why this extended period of not-quite-adulthood represents both vulnerability and opportunity for our children.

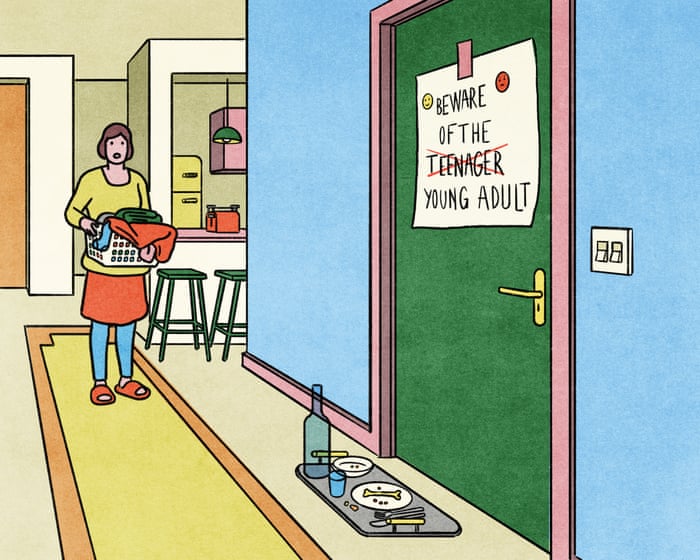

Parenting doesn’t stop when our children turn 18; it simply changes shape. Yet parenting adult children remains one of the least discussed and least understood aspects of family life.

With time and therapy, my daughter and I survived those fights and rebuilt a close relationship. I am profoundly grateful for that. In hindsight, the breakdown became a breakthrough: a necessary reconfiguration of our family system. It reset boundaries, opened more honest communication, and taught us to fight productively. That sounds like a happy ending, but the process was chaotic and raw. Here are some guiding principles for building good relationships with your adult children.

In previous generations, adulthood meant cutting ties at 18: you left home, got a job, married young, and rarely looked back. Today, it’s different. Many parents look at their adult children and wonder what has gone wrong. Compared with what they did at that age, their children’s slower path to independence can seem like arrested development.

Psychologist Jeffrey Arnett coined the term “emerging adulthood” for the years between 18 and 25, a phase of exploration and uncertainty when young people are “in between” adolescence and adulthood. It is a time to test, experience, and discover who they are. This isn’t evidence of moral decline but a developmental shift that reflects a radically different world. Technology, the women’s movement, and social change have transformed what it means to grow up.

The statistics tell the story starkly: about a third of young adults aged 18 to 34 now live with their parents. Nearly 60% of parents financially support an adult child. As difficult as that might be, it is a necessary adaptation to a profoundly altered economic and social reality. Parents rarely talk about how drained they feel or how to navigate it coherently.

I think of Sarah, a client in her mid-50s who came to therapy feeling utterly depleted. Three years earlier, her son Tom, 26, had moved back home after university. What began as a temporary arrangement…The temporary arrangement meant to last “just until he finds his feet” had hardened into an indefinite situation neither could define. Tom worked part-time at a coffee shop, spent his evenings gaming, contributed nothing to household expenses, and became defensive at any hint he should change.

Sarah felt caught between love and resentment. She cooked his meals, did his laundry, and walked on eggshells around his moods. Her own marriage suffered; her husband started coming home late to avoid the tension. Sarah couldn’t understand why Tom seemed so paralyzed when she felt she had given him everything. “I’ve failed him,” she said tearfully. “He can’t cope with adult life.”

Some parents struggle more with letting go, others with being needed; both require clear, loving boundaries.

As we worked together, a different story emerged. Sarah’s own mother had been cold and critical. Sarah had vowed to be different—warmer, more available. Yet she had overcompensated, shielding Tom from any struggle. She solved his problems and rescued him from consequences. Now, at 26, Tom had no confidence in his own abilities because he’d never had to develop them. And Sarah, exhausted from years of hypervigilance, felt angry at the very person she had tried so hard to protect.

The breakthrough came when Sarah began to see that her own anxiety, not Tom’s actual needs, was driving her behavior. We explored what she was truly afraid of: that if she didn’t manage his life, something terrible would happen. Beneath that lay an older fear: that she wasn’t good enough, and that love would disappear.

Sarah started small. She stopped doing Tom’s laundry. She calmly told him he needed to contribute a monthly amount to household costs. She resisted the urge to rescue him when he complained or sulked. It was agonizing. Tom was furious. He accused her of not caring and of suddenly changing the rules.

But gradually, they adapted. He picked up more shifts at work. He began, tentatively, to talk about moving out. The atmosphere at home lightened. Sarah’s husband started coming home earlier. In one session, Sarah told me, “Last week, Tom thanked me for dinner. It was the first time in three years he’d noticed I’d cooked. I realized I’d been so busy giving, I’d never let him give back.”

Research confirms what Sarah discovered: when adult children return home, parents’ quality of life and well-being often decline significantly, regardless of the reason for the return. Yet we rarely admit this openly, as it can feel like a betrayal. That silence keeps everyone trapped.

What changed for Sarah and Tom wasn’t that she loved him less—it was that she loved him differently. She began to trust him to navigate his own life. That shift, from anxious manager to respectful witness, is one of the hard tasks of parenting adult children.

The same dynamic plays out around money, career choices, and relationships. Parents see their children struggle and rush in to fix, advise, or rescue. It comes from love, but it often backfires. Studies show that excessive parental involvement—what researchers call “helicopter parenting”—is linked to poorer mental health in young adults, lower self-confidence, and difficulties with identity development. The very thing we do to help can end up hindering.

This extended closeness can be loving and necessary, but it is also fraught. Parents may feel resentful; children may feel infantilized. The key is clarity, not control. Have explicit conversations about money, chores, privacy, and expectations. Boundaries matter. It is the unspoken assumptions—those old, inherited patterns—that most often lead to conflict.

Young adults themselves point to what helps make a return home work: clear expectations discussed openly; making meaningful contributions to the household; being treated as adults, not teenagers; and having an exit plan with a timeline. This includes respecting their autonomy over their relationships, their phone, their finances, and their social life.

Sometimes it is the parent, not the child, who hThe issue isn’t whether your 28-year-old lives at home. It’s about whether the relationship has evolved to match their stage in life, or whether everyone is stuck repeating the same patterns from when they were a teenager.

This shift is difficult. For years, our role was to protect, guide, and keep our children safe. Then the task changes: we must step back and allow them to make their own choices and mistakes. That transition can feel confusing because, in some way, they will always be the little child we hold inside. It takes real psychological effort to love the child we actually have, not the one we imagined or might have chosen; to listen fully, respect their independence, and offer advice only when asked. As Anna Freud said, “A mother’s job is to be there to be left.”

Good-enough parenting of adult children requires a delicate balance: not to abandon them, but not to over-parent; to step out of the constant parent role and share more as equals; to stay connected without creating dependency. The real work is to let go of control without letting go of the connection.

There is a parenting model called Circle of Security, designed to help caregivers understand and meet children’s emotional needs in early childhood. The principle applies here, too. You want to be the safe place your adult children can return to, but also the support that encourages them to move out into independence. Some parents struggle more with letting go, others with no longer feeling needed; both situations require clear, loving boundaries.

What about when your child finds romantic relationships? As parents watch their adult children date and enjoy life, it can stir up envy for their youth—their vitality, the long life still ahead of them—even alongside feelings of pride and love. Acknowledging these emotions, rather than burying them in shame, helps us stay authentic and generous. The more we accept the reality of our own age and limits, the freer our children are to live fully.

Other difficulties can arise as roles shift. Unprocessed trauma from one generation can be passed to the next. When pain is buried instead of faced, it transmits through behavior, emotional reactions, and even biologically. Unprocessed trauma makes us more reactive: parents may become unpredictable or unreliable, leaving children anxious or hypervigilant. These patterns echo for decades until someone is ready to feel the pain and begin to heal it. Where trauma or neglect has shaped a family, estrangement becomes more likely—not because love is absent, but because it has felt too painful to express safely. It helps for parents to recognize the trauma they carry and aim to process it, not only for themselves but for the whole family.

Sometimes it is the parent, not the child, who has not matured. Adult children with immature or narcissistic parents often become caretakers, trying—and usually failing—to manage or placate the very people meant to protect them. The task here, for the children rather than the parents, is different but equally vital: to set limits without guilt, to see their parents’ limitations clearly, and to stop trying to earn a love that was conditional or inconsistent. Love may still be possible, but only from a safe emotional distance. In these cases, boundaries become the necessary form that love must take.

Another challenge arises when worldviews diverge—over politics, religion, gender, or lifestyle. The pandemic and the culture wars that followed have widened these divides. Parents often ask in therapy, “How did we raise someone who sees the world so differently from us?” This situation calls for humility. Love does not mean agreement. It means allowing for difference.Differences arise. The moment you try to win an argument, you risk the relationship. Curiosity is the antidote: ask rather than tell. Remember that every generation reacts against the one before it.

Your influence endures, but not through your opinions. It lives in how you embody love, respect, integrity, and kindness. You helped write the relational map inside your children—trust that, and trust them.

The greatest tensions often surface during transitions: when a child leaves home or returns, when a new partner joins the family, a grandparent dies, or someone loses a job. These moments reveal a family’s fault lines but also create opportunities for growth and repair.

Even the closest families face storms. Conflict with adult children can cut deep because it touches your identity—not just as a parent, but as someone who tried their best. The temptation is to try to fix it or to withdraw. It’s better to pause, acknowledge your part, apologize where needed, and listen with empathy. Repairing after conflict not only heals but strengthens emotional security and resilience on both sides.

For all its complexity, this stage can bring profound rewards. Conversations grow richer; humor deepens. You can enjoy your grown children as people in their own right—their quirks, passions, and wisdom.

As one mother recently told me, “It’s like watching your heart walk around outside your body, but now it walks confidently.” That captures the bittersweet beauty of it. If you can speak honestly, disagree respectfully, and laugh together, you have done something remarkable. You have turned a bond of dependency into a relationship of mutual respect—one that evolves as you both do.

Parenting does not end; it matures. And, like all mature love, it asks for courage: to learn continually, to forgive repeatedly, and to show up consistently—not as the all-knowing parent, but as a fellow human being who is still growing, too.

For my daughter, feeling listened to helped enormously. “Over time my rage decreased as I felt heard enough,” she says now. “Part of the developmental task of separating was proving wrong what I’d always feared—that if I showed my true, messy, struggling self, I wouldn’t be lovable. That love was conditional. Eventually, very messily, I learned I was loved as I am.”

Families are not static: they are living systems that constantly adapt. The best we can do, as parents, as children, as human beings, is to stay open: to listen, to grow, and to love, even when it is hard.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQs Extended Adolescence Parenting Adult Children

Understanding the Shift

Q What does it mean that adolescence now extends into the 30s

A It means the traditional markers of adulthoodlike financial independence marriage homeownership and stable career pathsare happening later for many people Young adults often spend their 20s and early 30s exploring education careers and relationships before settling into a more classic adult life

Q Is this just about failure to launch or is there more to it

A Its much more than that Economic factors cultural shifts and longer life expectancies have fundamentally changed the timeline This period sometimes called emerging adulthood is now a recognized life stage focused on identity exploration

Parenting Approach Mindset

Q How should my role as a parent change once my child is over 18

A Your role should shift from manager to consultant Your goal is no longer to control or direct their life but to offer guidance support and a safety net when they ask for it or truly need it

Q Whats the biggest mindset shift I need to make

A You need to accept your adult child as a fellow adult even if their life looks different from yours at their age Respect their autonomy and their right to make their own choicesand their own mistakes

Q How do I balance support with not enabling them

A Clear boundaries are key Support that helps them build skills and move forward is different from support that lets them avoid responsibilities Tie support to agreedupon goals

Communication Boundaries

Q How often should I call or check in

A Theres no magic number The key is to communicate their preferred way and respect their independence Ask them directly Whats a good rhythm for us to catch up and be prepared for less frequent contact than you might like

Q What if I disagree with their life choices

A Unless they are in danger your job is to listen not to judge or lecture You can express concern calmly once