As Venezuela’s skyline lit up under U.S. bombs, we witnessed the morbid symptoms of a declining empire. That might sound counterintuitive. After all, the U.S. has kidnapped a foreign leader, and Donald Trump has announced that he will “run” Venezuela. Surely this appears less like decay and more like intoxication—a superpower drunk on its own strength.

But Trump’s great virtue, if it can be called that, is candor. Previous U.S. presidents cloaked naked self-interest in the language of “democracy” and “human rights.” Trump discards the costume. In 2023, he boasted: “When I left, Venezuela was ready to collapse. We would have taken it over, we would have gotten all that oil, it would have been right next door.” This was no offhand remark. The logic of seizing oil, and much more, is laid out plainly in Trump’s recently published National Security Strategy.

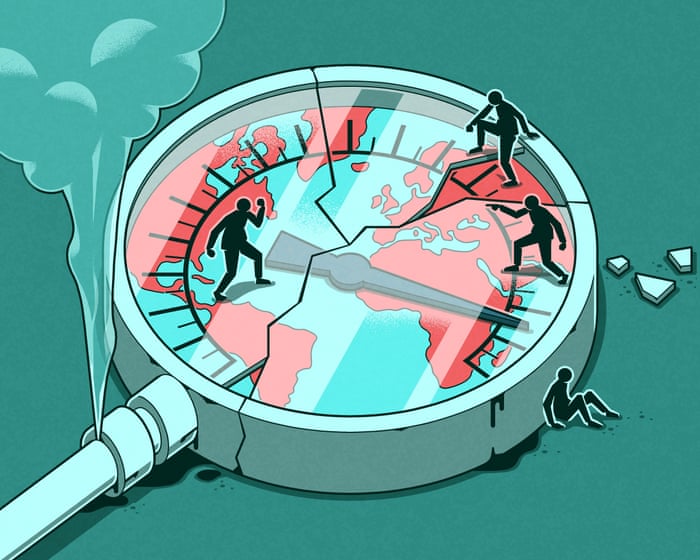

The document acknowledges something long denied in Washington: that U.S. global hegemony is over. “After the end of the Cold War, American foreign policy elites convinced themselves that permanent American domination of the entire world was in the best interests of our country,” it declares with thinly veiled contempt. “The days of the United States propping up the entire world order like Atlas are over.” These are the strategy’s blunt funeral rites for U.S. superpower status.

What replaces it is a world of rival empires, each enforcing its own sphere of influence. And for the U.S., that sphere is the Americas. “After years of neglect,” the strategy states, “the United States will reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere.” The Monroe Doctrine, formulated in the early 19th century, claimed to block European colonialism. In practice, it laid the groundwork for U.S. domination over its Latin American backyard.

Violence in Latin America facilitated by Washington is nothing new. My parents took in refugees who fled Chile’s right-wing dictatorship, installed after socialist president Salvador Allende was overthrown in a CIA-backed coup. “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go communist due to the irresponsibility of its people,” declared then U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Similar logic underpinned U.S. support for murderous regimes in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia, as well as across Central America and the Caribbean.

But over the last three decades, that domination has been challenged. The so-called “pink tide” of progressive governments, led by Brazil’s president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, sought to assert greater regional independence. And crucially, China—the main U.S. rival—has grown in power across the continent. Two-way trade between China and Latin America was 259 times larger in 2023 than in 1990. China is now the continent’s second-largest trading partner, behind only the U.S. At the end of the Cold War, it wasn’t even in the top ten. Trump’s assault on Venezuela is just the opening move in an attempt to reverse all of this.

The experience of Trump’s first term led too many to conclude that the strongman in the White House was all bluster. Back then, he reached an accommodation with the traditional Republican elite. The unwritten bargain was simple: deliver tax cuts and deregulation, and he could vent endlessly on social media. A second-term Trump would be a full-fat far-right regime.

When he threatens the democratically elected presidents of Colombia and Mexico—believe him. When he declares, with barely concealed relish, that “Cuba is ready to fall”—believe him. And when he states, “We do need Greenland, absolutely”—believe him. He really does intend to annex more than two million square kilometers of European territory.

If—when—Greenland is swallowed by a Trumpian empire, what…So, Trump will have taken note of Europe’s feeble response to his blatantly illegal move against Venezuela. But a U.S. seizure of Danish territory would surely mean the end of NATO, an alliance built on collective defense. Denmark’s land would be stolen just as brazenly as Russia’s swallowing of Ukraine. Whatever muted objections have come from London, Paris, or Berlin, the Western alliance would be finished.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, America’s elites convinced themselves of their military invincibility and that their economic model was the pinnacle of human progress. That arrogance led directly to the catastrophes in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya, and to the 2008 financial crash. U.S. elites promised their people utopian dreams, then dragged them from one disaster to another. Trumpism itself grew from the resulting mass disillusionment. But the “America First” response to U.S. decline is to abandon global dominance in favor of a hemispheric empire.

What does that leave for the U.S. itself? When America defeated Spain at the end of the 19th century and seized the Philippines, prominent citizens formed the American Anti-Imperialist League. “We hold that the policy known as imperialism is hostile to liberty and tends toward militarism,” they declared, “an evil from which it has been our glory to be free.”

“We assert that no nation can long endure half republic and half empire,” the Democratic Party stated in the 1900 presidential election, “and we warn the American people that imperialism abroad will lead quickly and inevitably to despotism at home.” In the end, informal empire replaced direct colonialism, and American democracy—always deeply flawed—survived.

Who would dismiss such warnings as exaggeration today? What happens abroad cannot be separated from what happens at home. This is the imperial “boomerang,” as Martinican author Aimé Césaire described it three-quarters of a century ago, analyzing how European colonialism returned to the continent as fascism. We have already seen the “war on terror” boomerang in this way: its language and logic repurposed for domestic repression. “The Democrat party is not a political party,” Trump’s deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller declared last summer. “It is a domestic extremist organization.” National Guard troops are deployed into Democratic-run cities like occupying forces, echoing the “surges” once unleashed on Afghanistan or Iraq.

Seen this way, Trump’s indulgence of Russian ambitions in Ukraine is hardly mysterious. Back in 2019, Russia reportedly proposed increasing U.S. influence in Venezuela in exchange for a U.S. retreat from Ukraine. Who knows if such a deal has been made. What is certainly true is that a new world order is being born—one where increasingly authoritarian powers use brute force to subjugate their neighbors and steal their resources. What once might have sounded like dystopian fantasy is being assembled in plain sight. The question is whether we have the means, willingness, and ability to fight back.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about the topic Trumps new world order is emerging and Venezuela is only the beginning framed in a natural tone with direct answers

BeginnerLevel Questions

1 What does Trumps new world order even mean

Its a phrase used by some commentators and supporters to describe a shift in US foreign policy they believe is driven by former President Donald Trumps America First approach It suggests moving away from traditional alliances and international institutions toward bilateral deals and a focus on national sovereignty

2 Why is Venezuela mentioned as only the beginning

Venezuela under Nicolás Maduro is often cited as an example of a socialist government with severe economic and humanitarian crises Proponents of this view argue that the US policy of maximum pressure on Venezuela was a template for confronting adversarial governments and reshaping regional influence

3 Is this an official policy or just a theory

It is primarily a political narrative and theory not an official doctrine While the America First philosophy was a stated policy of the Trump administration the idea of a coordinated new world order is an interpretation of various actions and statements not a formal government plan

4 What are the supposed benefits of this approach

Supporters argue it prioritizes American interests reduces costly foreign entanglements challenges globalist elites forces other nations to bear more of their own defense costs and takes a harder line against regimes like those in Venezuela Iran or North Korea

Advanced Practical Questions

5 How does this differ from previous US foreign policy

It contrasts with the postWWII bipartisan consensus that emphasized multilateralism and promoting democracy abroad This approach is more transactional skeptical of international agreements and willing to use economic tools like tariffs and sanctions unilaterally

6 What are the common criticisms or problems with this new world order idea

Critics say it undermines global stability weakens alliances that amplify US power cedes geopolitical ground to rivals like China and Russia and often aligns with authoritarian leaders They also argue the maximum pressure campaign on Venezuela failed to dislodge Maduro while worsening the humanitarian situation for civilians