My father passed away nine months ago, and last night, he drove me home in a taxi.

We first realized something was wrong when he stopped taking his insulin and began leaving his apartment at night without shoes, insisting there were “people in the plants” and the floor was “muddy water.” After several tests, he was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia, a condition that brings hallucinations and a swift decline in mental function.

He moved into a nursing home in central Stockholm, and I convinced myself everything would turn out fine. Dad would finally receive proper medication, physical therapy, new teeth, foot care, and treatment for his failing eyesight. I pictured visiting him with my sons, imagining we’d finally have the chance to talk about everything: why he had disappeared, what we could have done differently, and why I still clung to the naive hope that he would apologize.

In his first weeks there, he often told the nurses the story of how he met my mother. He was a 21-year-old store detective from Tunisia, using his sharp eyesight to catch shoplifters in a mall in Lausanne, Switzerland. She was an 18-year-old Swedish student secretary there to learn French. They met at a pub. He quoted Baudelaire. She returned to Sweden. Years of letters followed, leading to a reunion in Stockholm.

After their first kiss, Dad asked Mom what her surname, Bergman, meant in Swedish.

“Mountain man,” she said. He was amazed. His own surname, Khemiri, also meant “mountain man”—but in Arabic. It felt like fate, like the start of a love that would last forever. Their names bound them together in a world that seemed to say their love was impossible, given their differences in class, background, religion, skin color, and native language.

It wasn’t entirely accurate—Khemiri doesn’t literally translate to “mountain man” in Arabic. But my father was from Jendouba, Tunisia, near the Kroumirie mountains, and Kroumirie sounds a bit like Khemiri, so it felt true enough. His greatest heartbreak was their divorce. When Mom told him he had to move out, Dad cursed me and my brothers: “Your mother will never be able to raise three boys on her own,” he said. “You’ll end up homeless drug addicts.”

He vanished from our lives, and I spent years trying to prove him wrong. I became a writer, my middle brother an actor, and the youngest a psychiatrist. None of us are homeless. But after every breakup since, I’ve heard his voice: “I told you not to trust anyone.”

After Dad moved into the nursing home, I received a fellowship in New York and relocated there with my family. He never forgave me for leaving Sweden. He’d call five times a day to tell me the nurses were trying to poison him, that Mossad had bugged his room, that the plants were still full of people, and the muddy water on the floor was rising. He wanted to go to Tunisia, or Paris, or New York—anywhere but where he was.

“Nobody has visited me in weeks,” he’d say, which was odd because I knew my brothers had been there just the day before. “All I need is some physical presence,” he added, which struck me as ironic, since all his now-grown children had felt the same way when he disappeared.

After we hung up, my sons asked me what was wrong with Grandpa. I tried to explain: he’s sick, he’s old, he came from a poor background in a complicated country, with eight siblings and a mother who couldn’t read or write. He worked his whole life for financial stability, believing money could bring freedom and help him escape a painful past he never wanted to discuss. He had countless dreams—selling watches, importing perfumes, driving subways, bartending, teaching languages—always hoping for that one big break to change everything.

“Did he ever get rich?” my oldest son asked.

“It depends on what you mean by rich,” I said. “He saved some money, but he lost a lot of people along the way.”

I hugged my sons and promised myself I wouldn’t repeat my father’s mistakes—knowing full well how hard that can be.I would have made my own.

A few months before he died, he called me, lost in the city. It was raining, his leather jacket had been stolen, and he couldn’t find his way back to the nursing home. Fear shook his voice. “Turn on your camera, and I can guide you,” I told him. It took him a few minutes to find the button. When he showed me his surroundings, I said, “But Dad, you’re in your room.” “Are you sure?” he asked, gazing at his walls, his TV, the Tabarka jazz festival poster, as if seeing them for the first time.

Just days before he passed, I was in Paris reading from my latest novel, The Sisters. It follows three siblings over 35 years as they struggle to escape a family curse. I chose a chapter where a father makes his son cut his hair and then helps a shopkeeper threatened by a drunk. The chapter ends with: “I enjoyed turning my father into a story; somehow, it gave me power over him, it seemed like the only power I had.”

The next day, my brother texted: “Dad has stopped eating and drinking. The doctors are considering palliative care.” I stood there, staring at the screen, realizing how powerless my stories were against death.

I flew to Stockholm and spent three days and nights with my brothers at his bedside. He was breathing but couldn’t speak, looking at us without recognition. He resembled a baby bird, with thin, wing-like arms and gaps where his white teeth used to be.

“He can still hear you,” the nurses assured us, and we believed them.

We stayed by his side, playing Satie on repeat and sharing stories. Remember when he caught two rabbits with his bare hands, killed mosquitoes on the ceiling with towels, pretended to eat a wasp, danced like James Brown, defended us from racist skinheads, quoted Disney films, forgot our girlfriends’ names, warned us against politics, and said we were crazy to trust banks? Death seemed to be winning, but our stories fought back. Dementia had turned his mind into a desert, yet I imagined our tales planting seeds that might rouse him. We hoped for terminal lucidity, for him to speak, for an ending that made sense.

One afternoon, we filled the room with family: my mom, my brothers’ girlfriends, their children, older kids keeping their distance, toddlers climbing onto the bed fearlessly. For a moment, I thought I saw a smile flicker on his lips, but still no words.

My middle brother was the last to hear him speak. The day before I arrived, Dad looked up and said, “Tell Per-Olof I still love his daughter.” Per-Olof Bergman, my Swedish grandfather, died in 1993. My parents divorced in 1995. My father died in 2025.

For 22 years, I’ve written about families, perhaps as a rebellion against death. Every time I get a call about someone’s death, my brain whispers, “You can write about this.” It happened with my first girlfriend’s suicide, a childhood friend’s car crash, my grandfather, grandmother, cousin, and uncle.

For years, I felt guilty about that reflex. Now I see it as a defense mechanism—an illusion of control: “Don’t worry, you’re not powerless. You can craft a vivid opening and a strong ending, turn loss into words, and replace the dead with sentences.”

His breathing grew shallow. We forgave him, we cried, we waited. He didn’t wake to say he loved us.

And in a way, we all do this: we lose, we tell stories, we tell stories, and then we die. The best we can hope for is that time takes us. No wonder we desperately seek control, narrative structure, a happy ending.

But sitting beside my dying father, I didn’t think about writing. Maybe because I’d already mourned him. Once, he told me, “Everything you have, you got from me. You wouldn’t be a writer without me.”I think he was right, but I believe his absence shaped me more than his presence ever did. His breathing grew faint. We said our goodbyes, forgave him, and wept. We waited, and waited some more. We must have said goodbye at least eight times.

On the third night, at 2:30 a.m., his breathing slowed. I woke my brothers, and we gathered around him. His forehead felt cold. There were long silences, then another breath. Silence. Breath. Silence. Breath. Then, just silence. A brief moment of pain, a gurgling sound, and then more silence.

He didn’t wake to tell us he loved us. He didn’t explain why things turned out as they did. He just breathed, and breathed, and then he stopped.

After he died, I flew to Tunisia to collect letters and photos and to meet grieving cousins and aunts. Even though he was gone, I kept seeing him everywhere. He was driving every car, standing behind every bar. The security guard who told me the mosque in Tunis was closing had his eyes. The bald man who tried to lure me down an alley in the souk had his hands and homemade tattoos. My aunt smelled like him; my uncle laughed like him. I had never been to Tunisia without him, and my mind refused to let him die.

Back in New York, he appeared less often. In April, a younger version of him sold halal food on 47th Street. In June, a middle-aged lookalike refereed my son’s flag football game in New Jersey. “Didn’t the referee look like your grandfather?” I asked on the way home. My son had headphones on and didn’t answer.

My father died eight months ago, and last night he drove me home in a taxi. I leaned forward to see if it was really him—same neck, same hair, same shoulders. But when we hit a pothole on Flatbush Avenue, he turned to me and said, “Sorry.”

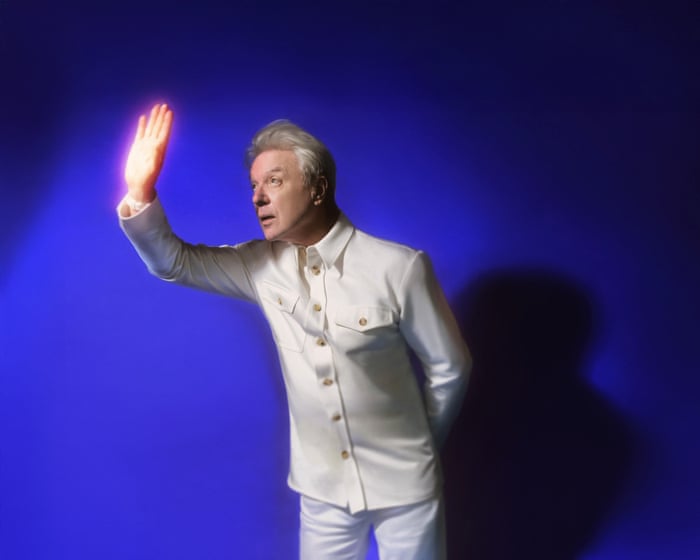

Jonas Hassen Khemiri is a Swedish novelist and playwright. His most recent novel, The Sisters, is his first written originally in English.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about the topic of a fathers curse and lingering presence designed with clear natural questions and direct answers

General Beginner Questions

1 What does it mean when someone says they feel a curse on their family

A family curse is a belief that a negative pattern like bad luck illness or tragedy is passed down through generations often due to a specific past event or a pronouncement from an ancestor

2 Is it normal to feel a deceased parents presence after theyve died

Yes its a very common experience It can be a part of the grieving process where your mind holds onto their memory so strongly that it feels like they are still with you

3 Why would I feel my fathers presence if he was abusive or abandoned us

This is often due to unresolved emotional conflict The strong feelings of anger hurt or a need for answers dont disappear with his death and this emotional energy can manifest as a feeling of his presence

4 Could this feeling actually be a ghost or spirit

Some people and cultures believe it could be Others see it as a psychological phenomenon Theres no scientific proof for ghosts so it often comes down to personal belief

Deeper Advanced Questions

5 How can I tell the difference between grief and a real spiritual presence

This can be difficult Griefrelated feelings are often tied to your own memories and emotions A perceived spiritual presence might feel like it has its own independent intelligence bringing specific messages or interacting with your environment in unexplained ways

6 What are common signs that make people believe theyre being followed by a spirit

People report things like hearing their name called seeing fleeting shadows objects moving on their own recurring dreams about the person or a constant feeling of being watched

7 Can a curse or negative energy affect my mental health

Absolutely Believing you are cursed or haunted can create intense anxiety depression and a feeling of powerlessness It can become a selffulfilling prophecy where you subconsciously expect and attract negative outcomes

8 My father cursed us before he died Is that curse now binding because hes gone

From a spiritual perspective a curse often holds power only if you believe in it and give it energy His death doesnt automatically make it more real