On the night of November 2, 1975, Pier Paolo Pasolini was murdered. His brutally beaten body was discovered the next morning on a patch of wasteland in Ostia, near Rome, so disfigured that his famous face was barely recognizable. Italy’s leading intellectual, artist, provocateur, moral voice, and openly gay man was dead at 53, his controversial final film still being edited. Newspapers the next day declared, “Assassinato Pasolini,” alongside photos of the 17-year-old accused of killing him. Given Pasolini’s known attraction to working-class male prostitutes, the immediate assumption was that a casual encounter had turned deadly.

Some deaths are so symbolic that they come to define a person, distorting how their entire life is viewed. In this reductive way of thinking, Virginia Woolf is forever walking into the River Ouse where she drowned. Similarly, Pasolini’s entire body of work is often interpreted through the lens of his murder by a young sex worker, seen as the final, inevitable outcome of his risky lifestyle.

But what if that was the point? What if his killing was deliberately staged to make it look like he had brought about his own demise—a fitting punishment, in the eyes of conservatives, for the perceived deviance that marked both his art and his life?

And what if this was also an attempt to tarnish his legacy and drown out the urgent warnings he had been voicing in his final years? In a famous essay published a year before his death in Italy’s leading newspaper, Il Corriere della Sera, Pasolini repeatedly stated, “I know.” What he knew—and refused to stay silent about—was the true nature of power and corruption during Italy’s violent 1970s, the so-called “Years of Lead,” marked by assassinations and terrorist attacks from both the far left and right. He understood that fascism had not ended but was evolving, resurfacing in a new form to dominate a society sedated by the shallow temptations of consumerism. Was Pasolini wrong in his predictions? I believe we all know the answer.

Pasolini was born in Bologna in 1922, the year Mussolini rose to power, into a military family. He spent influential years in his mother’s hometown of Casarsa, in the rural region of Friuli, after his father was arrested for gambling debts. The divide between his parents deepened during World War II. His mother, Susanna, was a schoolteacher who cherished literature and art, while his father, Carlo Alberto, was a staunch fascist and army officer who spent much of the war in a British POW camp in Kenya.

Pasolini studied literature at Bologna University but retreated to Friuli with his mother and younger brother, Guido, when bombing made the city unsafe. He became captivated by the region’s beauty and its pure, ancient dialect—his mother tongue, spoken by peasants and largely absent from literature. In 1942, he published his first collection of poems, Poesie a Casarsa, written in that dialect. But as fighting intensified after Italy’s armistice, even Friuli became dangerous. Guido joined the resistance and was executed by a rival partisan group—a tragedy that drew Pasolini and his mother even closer.

Part of Friuli’s appeal was erotic. It was here that Pasolini discovered his attraction to peasant and street boys—often pockmarked, homophobic, and involved in petty crime—who would become central to his life and work. This soon brought him into conflict with authority. In the late…In the 1940s, he faced charges of corrupting minors over an alleged sexual encounter with three teenagers. Although he was later cleared, the scandal forced him and Susanna to relocate once more, this time to Rome.

They arrived in a city still reeling from the aftermath of war—the Rome of Bicycle Thieves, a place in ruins, its slums filled with a new urban working class who had fled poverty in the rural south. Pasolini found work as a teacher and threw himself into learning another hidden language: Romanaccio, the street dialect spoken by the unruly young men he befriended. He called them ragazzi di vita in his 1955 novel, which established his reputation—”the boys of life.” They were pockmarked hustlers and petty thieves, slim-hipped and amoral, often homophobic, and almost always straight. These were the boys he placed at the center of his books, his films, his poetry, and his life.

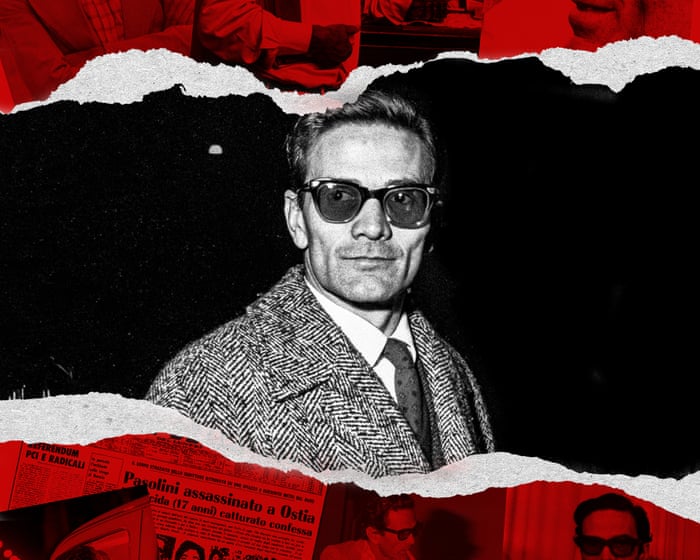

In photographs from this time, you can see Pasolini—a slight, slender figure with bandy legs, a mackintosh over his tailored suit, dark hair slicked back from an intense face with sharp cheekbones. He was an observer, a driven artist, and a passionate football player. He made his way to Cinecittà, Rome’s famous film studio, working as a scriptwriter. He assisted Fellini on Nights of Cabiria, then struck out on his own, writing and directing Accattone in 1961. The film was a neorealist portrait of a pimp—played by a real street kid, Franco Citti—and his bleak life in a Roman slum.

A lesser artist might have stuck to that style for years, but Pasolini quickly showed the remarkable depth and originality of his talent. He made overtly political films like Pigsty and Theorem, fueled by his contempt for the self-satisfied middle class. He told the story of Christ in The Gospel According to St. Matthew and turned to classical tales as well, creating raw, visceral adaptations of Oedipus Rex and Medea (starring Maria Callas), along with Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, Boccaccio’s The Decameron, and The Arabian Nights in his Trilogy of Life.

There is nothing else in cinema quite like these films—bawdy yet poetic, visually sublime, and deeply engaged with ideas. Many of them featured Pasolini’s great love and longtime companion, Ninetto Davoli, a shambling innocent from Calabria with an infectious, wide grin. Pasolini’s habit of casting non-professional actors lent his films a strange, unsteady realism—as if a Renaissance painting had sprung to life.

By his fifties, he was internationally famous and a constant target of controversy. He was considered a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, yet he had also endured 33 trials on fabricated or exaggerated charges—public obscenity, contempt of religion, and, most bizarrely, attempted robbery, allegedly with a black pistol loaded with a golden bullet. Pasolini didn’t even own a gun.

His art was never dogmatic, but it was always political. He had joined the Communist Party in his youth and was quickly expelled for his open homosexuality. He was criticized as often by the left as by the right, but despite being a thorn in everyone’s side, he remained aligned with communism and the radical left. In the 1970s, he grew increasingly outspoken on political issues, using essays in Il Corriere to address industrialization, corruption, violence, sex, and Italy’s future.

In his most famous essay, published in November 1974 and known in Italy as Io so (“I Know”), he claimed to know the names of those involved in “a series of coups instituted for the preservation of power,” including the deadly bombings in Milan and Brescia. During the Years of Lead, the far right employed a “strategy of tension” to discredit the left and push the country toward authoritarianism. Pasolini believed that among those responsible were figures within the state itself.Responsible figures in the government, the secret service, and the church were involved. He mentioned his novel in progress, Petrolio, where he planned to expose these corruptions. “I believe it is unlikely that my ongoing novel is mistaken or disconnected from reality, and that its references to real people and events are inaccurate,” he added.

The final film is the most grim. No horror movie since has matched Salò (1975), and no graphic torture film comes close to its chilling precision or its profound moral outrage. Based on De Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom and set in the Italian countryside at the end of World War II, it is a terrifying allegory about fascism and obedience, exploring both sides of totalitarianism. Like De Sade’s writing, it focuses on power—who holds it and who suffers under it—rather than pleasure. It remains an apocalyptic masterpiece that is almost impossible to watch; as writer and critic Gary Indiana noted in an essay praising its enduring power to disturb, it is “off the reservation, proscribed.”

In my new novel, The Silver Book, I centered the story around the making of Salò. I imagined Pasolini at work, wearing a tight Missoni sweater and dark glasses, moving swiftly between scenes with an Arriflex camera on his shoulder, supervising the creation of fake feces from crushed biscuits and chocolate for the infamous scene involving excrement. Unlike Fellini, he didn’t intimidate his collaborators. He was respected and admired, yet also isolated and alone. His nightly habit of seeking encounters—explored in his poem “Solitude”—made him wonder if it was just another way to be by himself.

Pasolini foresaw what was to come. Like the most exceptional artists, he possessed a kind of second sight.

Ninetto had married two years prior, and this loss plunged Pasolini into deep despair, which seeped into the film. He had publicly rejected his earlier, joyful Trilogy of Life. Now, for him, sex represented death and suffering. Utopia seemed impossible. Yet, when asked who the intended audience for Salò was, he seriously replied: everyone. He still believed that art could cast a counter-spell and jolt people awake. He hadn’t given up hope.

One theory about Pasolini’s death is that he was tricked into going to Ostia to retrieve stolen reels of Salò. I incorporated this idea into my novel but chose not to depict his murder directly, in which he was brutally beaten, his groin crushed, his ear nearly cut off, and then run over by his own silver Alfa Romeo, causing his heart to rupture. The young man convicted of his murder had only a few small bloodstains on him and no injuries, despite supposedly beating someone to death. Another line from Io so hints at what likely happened: “I know the names of the shadowy and powerful individuals behind the tragic youths who committed suicidal fascist acts or the common criminals, Sicilian and others, hired as killers and assassins.”

Pasolini saw what was coming. Like the rarest artists, he had the gift of second sight, which is another way of saying he paid attention.He watched, listened, and understood how to read the signs. On his final afternoon, he happened to be interviewed by La Stampa. Days after his death, his last recorded words appeared in a sold-out edition—a prophecy from beyond the grave.

He spoke of how ordinary life was being twisted by the craving for possessions, because society teaches that “wanting something is a virtue.” This obsession touched every part of life, he said, with the poor using crowbars to take what they wanted, while the rich turned to the stock market. Reflecting on his nightly journeys into Rome’s underworld, he described descending into hell and returning with the truth.

When the journalist asked what that truth was, Pasolini replied: the proof of “a shared, compulsory, and misguided education that drives us to own everything at any cost.” He saw everyone as victims in this system—no doubt thinking of his film Salò, where victims and oppressors are trapped in a horrifying dance. And he saw everyone as guilty, too, because they willingly ignored the consequences in pursuit of personal profit. He stressed that it wasn’t about blaming individuals or labeling people good or bad. It was a total system, though unlike in Salò, there was a way out—a chance to break free from its sinister, seductive grip.

As always, his language was more poetic than political, rich with metaphor and eerie warnings. “I go down into hell and uncover things that don’t disturb others’ peace,” he said. “But be careful. Hell is rising toward the rest of you.” Near the end of the conversation, he seemed to grow impatient with the interviewer’s attempts to pin down his views. “Everybody knows I pay for my own experiences firsthand,” he remarked. “But there are also my books and my films. Maybe I’m wrong, but I keep saying we are all in danger.”

The journalist asked how Pasolini himself could avoid this danger. It was growing dark, and the room had no light. Pasolini said he would think about it overnight and answer in the morning. But by morning, he was dead.

I believe Pasolini was right, and I’m convinced his persistent warnings led to his murder. He foresaw the future we now inhabit long before anyone else. He saw capitalism corroding into fascism, or fascism infiltrating and seizing capitalism—how something that seemed benign would corrupt and destroy older ways of life. He knew that compliance and complicity were deadly. He warned about the ecological damage of industrialization. He predicted how television would reshape politics, though he died before Silvio Berlusconi rose to power. I doubt the ascent of Trump, a politician shaped in Berlusconi’s image, would have surprised him.

He wasn’t perfect. He was nostalgic for a rural, peasant Italy and willfully blind to the drawbacks of that ideal. He opposed abortion and mass education; in 1968, he sided with the French police against the students. His poetry could be self-indulgent, his paintings weak. He paid young men for sex, yet he also took them seriously, listened to them, found them work, and offered steady support. He was a visionary, an artist of unshakable moral conviction. He refused to stay silent.

The timing of his death makes it seem as if Salò was his final, bleak statement, but even on his last night, over dinner, he was discussing his next film. There was more work to come—unimaginable in form, unprecedented in style. He ate steak, he went out. He was hungry, you see. He was always on the side of life.

Olivia Laing’s The Silver Book will be published on November 6 by Hamish Hamilton.Hamilton. The Barbican in London will host a 50th-anniversary screening of Salò on November 11th.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about the enduring relevance of Pier Paolo Pasolinis insights into fascism fifty years after his death

General Beginner Questions

1 Who was Pier Paolo Pasolini

Pier Paolo Pasolini was a famous Italian writer poet filmmaker and intellectual He was a controversial and brilliant figure known for his sharp critiques of society politics and the rising consumer culture

2 How did Pasolini die

He died violently on November 2 1975 in a stillmurky incident on a beach near Rome Officially he was murdered by a young male prostitute but many believe his death was a political assassination because of his outspoken criticism of powerful figures and institutions

3 What did Pasolini say about fascism

Pasolini argued that the old overt fascism of Mussolini was being replaced by a new more insidious form He believed this new fascism was rooted in consumerism mass media and the destruction of traditional cultures and critical thought

4 Why are his ideas more relevant today than ever

Many people see his predictions coming true The dominance of consumer culture the power of television and social media to shape uniform opinions and the erosion of local traditions and languages mirror the new fascism he warned us about

Deeper Advanced Questions

5 What is the difference between old and new fascism according to Pasolini

Old Fascism Used violence censorship and patriotic symbols to force conformity and obedience through fear

New Fascism Uses consumerism and mass media to make people want to conform It doesnt force you to be alike it convinces you that happiness comes from buying the same things and having the same desires creating a voluntary and cheerful conformity

6 What did he mean by the genocide of fireflies

This was a powerful metaphor he used He noticed that fireflies were disappearing due to pollution and pesticides He compared this to the disappearance of unique rebellious and authentic ways of life and people who were being wiped out by the pollution of a new homogenizing consumer society

7 How does his concept of new fascism relate to modern social media

Pasolini warned that television was creating a single standardized