I once spent a frustrating week showing a Russian friend around London. He insisted on seeing everything but admired nothing. Museums, monuments, shops—all were compared unfavorably to St. Petersburg and Moscow. After a few days, this grew tiresome, so I asked if there was anything about Britain that impressed him. “The stability,” he replied without hesitation. “You can feel the stability.”

That was a different world—the late 1990s. I don’t recall the exact year, but I understood what he meant because I had felt the same culture shock in reverse when I first visited Russia.

It was the decade of chaotic democracy under Boris Yeltsin. The Soviet Union had collapsed, and it wasn’t clear where the unraveling would end. Criminal violence was widespread. A drunk president was propped up by a lawless oligarchy, looting state assets under the guise of privatization. No one who witnessed Russia’s trauma during that time was surprised by the nostalgia it sparked for the pre-democratic era. Soviet power was unaccountable, but at least it was predictable.

Vladimir Putin is as corrupt as anyone else who rose to the top under Yeltsin. But he restored order and national pride, which mattered more to most Russians than the gradual suffocation of political freedom.

This dilemma isn’t familiar to British voters, because democracy and stability have rarely seemed at odds. Our multi-party system allows peaceful competition between different political and economic interests. The opposition can become the government without bloodshed, and defeated leaders step down without fear of retribution. Under rules-based competition, democracies can manage dissent before it turns into revolution. This makes them innovative and resilient—the very qualities that helped free societies outperform tyrannies in the 20th century. Now, vengeful dictatorships want a rematch. Putin believes he can turn the West’s greatest strength into its greatest weakness.

An authoritarian megalomaniac sees value in a political system only if it doesn’t obstruct the leader’s will. To such a ruler, liberal democracy looks stupid and weak—submitting its leaders to the contradictory whims of ordinary voters. It follows, then, that the way to hasten democracy’s failure is to amplify those contradictions: nurture division, accelerate polarization, and shrink the space for compromise until representative government grinds to a halt.

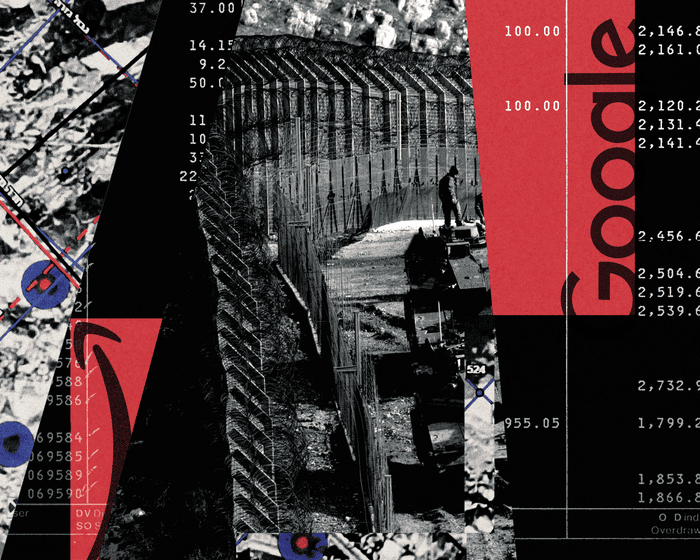

The theory has roots in Soviet-era tactics, but the old KGB was limited by the clumsy, analog logistics of recruiting agents and meddling abroad. The digital age makes it cheaper and scalable.

Traditional subversion methods are still in play. Reform UK’s former leader in Wales, Nathan Gill, is now in jail after pleading guilty to bribery charges from his time as a UKIP and Brexit Party MEP. He accepted tens of thousands of pounds to promote pro-Russian interests in the European Parliament and offered to recruit colleagues to do the same—though there’s no evidence he succeeded.

The case has led the government to launch an inquiry into foreign influence in UK politics. Its focus is the post-Brexit period, not because Kremlin meddling is new, but because digging into older interference—which could tarnish the democratic legitimacy of the Brexit campaign—is seen as too socially and politically explosive.

Back in 2016, the Kremlin clearly preferred that Britain harm itself and the EU by torching their mutually beneficial alliance, just as Putin had a clear stake in Donald Trump defeating Hillary Clinton in that year’s U.S. presidential election.

But the method isn’t limited to specific geopolitical goals. Any divergence of opinion is ripe for radicalization through the inflammatory algorithms of social media. A 2018 U.S. Senate committee investigation found that Russian troll accounts were posting messages supporting Black Lives Matter while also cheering Confederate flags.Digital silos are being targeted to weaken the social bonds that hold multicultural societies together—an attack on democracy’s immune system. This threat has only grown with AI, which floods the information space with synthetic news and convincing deepfakes.

In a recent speech, MI6’s new director, Blaise Metreweli, highlighted this challenge, describing the current security environment as a “space between peace and war.” While Russia isn’t the only adversary, Putin stands out as the primary threat, exporting chaos through methods like drone incursions along NATO borders, cyberattacks on infrastructure, arson, and sabotage. Such provocations can backfire by alerting the public to otherwise hidden dangers.

A more subtle threat is the poisoning of democratic debate. It blurs the lines between deliberate service to a hostile state and unwitting cooperation, or between treason and gullible dogma. Take someone like Gill: though motivated by greed, he may have believed the arguments he was paid to promote. On the fringes of British politics, both on the radical right and left—among Trump loyalists and so-called “anti-imperialist” NATO skeptics—Moscow’s talking points often get amplified for free.

Ideology isn’t the main tool for undermining Western democracies. Often, apathy and disengagement are more damaging than activism. The most corrosive product of digital disinformation is cynicism—the belief that all politicians are equally dishonest and that truth is nowhere to be found. This despair can lead people to dismiss democracy itself as a sham.

Putin’s strategy is also driven by a desire to avenge Russia’s humiliation in the 1990s. He saw democracy during the Yeltsin era as a tool for elites to legitimize plunder. While the liberal script differed from the old Communist party line, the hypocrisy felt the same. From that perspective, if democracy failed in Russia, it must be flawed everywhere. This view absolves Russians of responsibility for their country’s struggles, blaming instead the “great lie” of political freedom pushed by the enemy.

This same resentment fuels the denial of Ukraine’s sovereignty, seen as part of a long-standing conspiracy to weaken Russia. NATO’s support for Kyiv’s self-determination is dismissed as a cover for that plot.

By sowing discord and eroding consensus, Putin aims to strip Western societies of the stability that once made them powerful. In his vision, the lesson of the Cold War would be reversed: instead of authoritarian regimes collapsing as people yearn for freedom, disillusioned citizens in failing liberal democracies would turn to strongmen for order.

That dark possibility can seem alarmingly real, especially given the chaos of Trump’s rule in the U.S. It’s a reminder for Europe to stay vigilant. Ultimately, dictators underestimate societies built on laws and institutions because they can’t comprehend a system stronger than one person’s rule. They fail to grasp democracy’s most powerful truth: it outlives every tyrant who tries to prove it a lie.The author is a columnist for The Guardian.

If you have thoughts on the topics discussed in this article and would like to share them, you can submit a letter for possible publication in our letters section. Please email your response, which should be no more than 300 words, by clicking here.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQs Democracy as a Strength Not a Weakness

BeginnerLevel Questions

Q1 What does it mean when people say Putin believes democracy is the Wests weakness

A1 It refers to the idea that leaders like Vladimir Putin view the open sometimes messy nature of democratic systemswith free debate changing leaders and public dissentas a source of instability and slow decisionmaking making democracies easier to manipulate or defeat

Q2 Isnt it true that democracies can be slow and divided How is that a strength

A2 Yes democracies can be slower because they require debate and consensus However this process leads to more considered legitimate decisions that have broader public support The ability to openly debate and correct course is a resilience that closed systems lack

Q3 What are the core strengths of a democratic system

A3 Core strengths include Accountability Innovation Resilience and Legitimacy

Q4 Can you give a realworld example where democracy proved to be a strength

A4 During the COVID19 pandemic many democracies initially struggled but their free press and scientific debate allowed for rapid public scrutiny policy adjustments and the incredibly fast development of vaccines through open competitive innovation

Advanced Practical Questions

Q5 How do democracies turn internal criticism and dissent into an advantage

A5 Public criticism acts as an early warning system exposing problems before they become catastrophic A free press and political opposition force governments to justify their actions leading to better outcomes and preventing groupthink

Q6 Autocracies seem efficient in the short term How does democracy win in the long run

A6 While autocracies may enforce quick decisions they often suppress the feedback and creativity needed for longterm health Democracies foster economic innovation attract global talent and build stronger social contracts leading to more sustainable and adaptable societies over decades

Q7 What about democratic backsliding or polarization Doesnt that prove Putins point

A7 Internal challenges are real but they are