Many people speak of a childhood teacher who changed them, someone who revealed knowledge about the world that they carry for the rest of their lives. I didn’t have one of those. It wasn’t until I was 24 and living in Paris, when I stumbled into Philippe’s class almost by accident, that this happened. Provocative, demanding, deliberately inappropriate, and utterly hilarious, Philippe taught me not to carry anything—no baggage, no ideas; knowing nothing is all you need. Because we are all ridiculous.

His mother was Spanish, and we would relish her meals when she came to cook for him, or rather with him, in his apartment lined with his writings, many of which had “rêves” (dreams) inscribed on the spine. He referred to his father as “ce salaud bourgeois” (that bourgeois arsehole) and delighted in telling me the story of being thrown out of school at age eight for punching the gymnastics teacher, who was trying to instill discipline in young boys by turning them into military martinets.

Among the professions and attitudes that earned his ire—the military, the church, hypocrisy, sham, inauthenticity, politicians, academics, and fascists—“collaborateurs” held a special place in his heart. For a boy who grew up in postwar France, this slur was reserved for the most deserving. “C’est un collabo de merde de chien”—a dog-shit collaborator, though that translation fails to capture the pleasurable disgust and gastronomic relish with which he spat these words out from under his moustache.

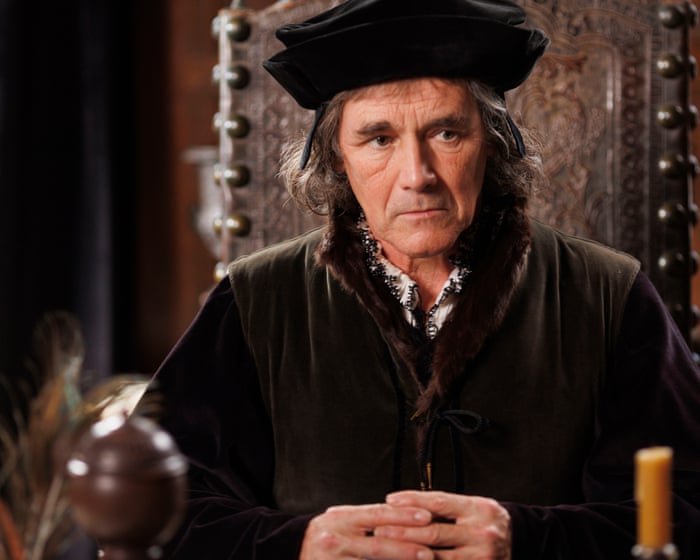

The moustache, a tangled mass of unruly black wire obscuring the entire area between his nose and lower lip, fascinated me from our first meeting on a cold November evening in 1980 at his studio on Rue Alfred de Vigny. That, and his pipe clenched tight between his teeth. Then there was his wild hair, a bright green sagging sweater, aging boots, and eyes—framed by round glasses—that missed nothing, took nothing seriously, and ferociously studied every possibility for hilarity or pretension.

The room was full of people who didn’t know what to expect but had heard that Philippe Gaulier offered something you couldn’t get anywhere else. I shook his hand. Pause. A look. “Bonsoir.” “Bonsoir.” Pause. Another look. “You arre eeengleesh?” “Yes… er… Oui.” “Tout le monde a des problèmes.” What did he just say? Everyone has problems? Hand still held. Eyes sparkling. Wicked laughter. First lesson.

“Moi,” placing his hand on his belly, “moi, je suis le professeur, vous… vous êtes des élèves.” Rules were established—rules of the game. From the outset, the game was that he was the teacher, and you were the pupils. The gymnastics teacher was parodied; the power relationship was offered as a structure to be undermined and shattered with laughter.

There was no style, no set ideas. Each person was scrupulously attended to, taken apart, built up again, invited, insulted, cajoled, delighted, and, most importantly, played with. He played with each of us with infinite generosity, stomach-aching hilarity, indefatigable persistence, and utterly spontaneous flexibility.

We learned to fail and start again; we learned to jettison our own ideas, because ideas were never the problem—only performing them. When people laugh at you, it reveals a truth, which is why we hate being laughed at in real life. But with Philippe, we could learn that failing to embrace this vulnerable sense of exposure was inimical to revealing our humanity.

Sharing this fallibility in a complicit relationship with the audience is a radical act—an anarchic joining found in no other art form.”If an actor has forgotten how to play like a child, they should not be an actor,” he would tell me as he took me to the bar during the lunch break before the afternoon session. By then, he had decided I was his assistant, and we needed to discuss the serious business of the afternoon.

“Here, my boy, we’ll go find some inspiration,” he would say. Then, leaning across the bar with his pipe in his mouth, he’d order, “Two large gin martinis…”

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about Simon McBurneys experience with Philippe Gaulier framed in a natural conversational tone

Beginner General Questions

1 Who is Philippe Gaulier and why is he so important

Philippe Gaulier is a legendary French theatre teacher and former student of the famous mime Jacques Lecoq He is known for his brutally honest hilarious and transformative school in Paris which focuses on finding an actors unique clown and joyful playfulness

2 What does Simon McBurney mean by Absolutely hilarious

Hes referring to Gauliers core teaching that true comedy and compelling performance come from a state of genuine playful pleasure If youre having fun and are absolutely hilarious to yourself the audience will be captivated Its not about telling jokes but about a state of being

3 How did Gaulier transform Simon McBurneys life

McBurney says Gaulier broke down his serious intellectual approach to theatre He pushed him to stop trying to be good or meaningful and instead to connect with a sense of childlike play failure and pleasure This became the foundation for McBurneys innovative work with his company Complicité

4 What is the clown in Gauliers teaching

Its not about a circus clown with a red nose Its your unique ridiculous vulnerable and authentic self that emerges when you are playing freely in front of others Its about being seen and finding pleasure in the moment

5 Is Gauliers school just for clowns and comedians

No While famous for comedy actors directors writers and even people outside the arts attend The training is about presence creativity listening and overcoming selfcensorshipvaluable skills for anyone

Advanced Practical Questions

6 What is le jeu and le plaisir

These are Gauliers central concepts