Tucked away in a Covent Garden alley, on the facade of a former banana warehouse, hangs a blue plaque. It reads: “Monty Python, Film Maker, Lived Here, 1976–1987.” The plaque is easy to overlook—instead of being at eye level like most, it’s positioned on the first floor, almost as if the blue plaque committee lost faith in their own unusual joke. Or maybe John Cleese installed it himself.

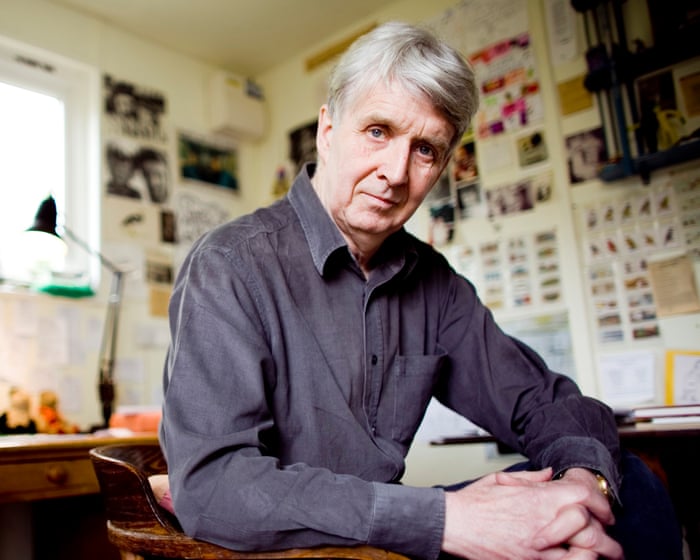

Terry Gilliam arrives, and I immediately admire his jacket, which looks as though it was pieced together from scraps of blankets. “I like it too,” he says. “I bought it 30 years ago from a secondhand shop in New York.” We’re about to stroll through London, revisiting spots that have been important in his career as he nears his 85th birthday.

He confirms the dates on the plaque are correct. After the success of 1975’s Monty Python and the Holy Grail, which Gilliam co-directed with Terry Jones, the group had money to spare. So he, Michael Palin, and special effects expert Julian Doyle rented this building. The ground floor was used for recording Monty Python albums, while upstairs housed a studio where they created effects for Life of Brian, such as the spaceship crash. “We went to the local magic shop, bought exploding cigars, emptied the gunpowder, then broke a lightbulb and placed it on the filament,” he recalls with a giggle. Gilliam laughs often—a playful, mischievous chuckle. I had half-expected a grumpy old man. “At home I am,” he admits. “This is a performance.”

The neighborhood has become much more upscale. He reminisces about a mother and son who used to prepare their hotdog stall here before pushing it to Leicester Square. “They were filthy, totally Dickensian. I was in love with this place.” Nearby, there was an armourer who crafted armor the traditional way, hammering away at steel. It sounds like something out of one of his films, but a 1978 New York Times article confirms the Covent Garden armourer’s existence. Now, the area is filled with high-end coffee shops and hair salons. The Python’s old warehouse is now a Neal’s Yard Remedies store, currently under renovation. A worker notices Gilliam gazing up at the plaque and asks who he is. “Terry Gilliam,” he replies. The man nods, but without recognition—the wrong generation.

Gilliam’s career took off after he arrived by boat from the US in 1968 and joined the TV sketch show Monty Python’s Flying Circus. I ask if he ever felt like an outsider. The others had attended Oxford or Cambridge, while he described himself as “a monosyllabic Minnesota farm boy,” though one with a gift for animation.

“I was in awe,” he says. “They were so clever with words, great performers. I was just this guy cutting up pieces of paper and messing around. But my sense of humor matched theirs, even if mine was more visual. That’s the thing about Python: the chemistry among the six of us. We were different, we argued, but together we created an inexplicable chemical magic.” Who could have guessed that the only thing missing would be a giant, stomping foot?

Initially credited as the animator, Gilliam soon became an essential part of Python, co-directing Holy Grail and launching a new phase of directing his own films. The building we’re standing outside played a role in that chapter: he edited his 1985 satirical Orwellian fantasy Brazil here and cast Time Bandits, the film that came before Brazil in his Trilogy of Imagination. As we walk and talk, he notes, “Luckily, I’m not as recognizable as Cleese or Palin.” Still, he enjoys chatting with people, stopping to speak with a woman in a key-cutting booth. “Keep cutting those keys,” he tells her.Liam has nominal aphasia, which makes it hard for him to recall the names of objects. There was a time when he couldn’t remember his wife’s name—it’s Maggie Weston; they met when she was a makeup artist on Monty Python. He reflects that much of aging feels like a regression. “I’m actually reverting back to the clay God used to create Adam. And what does Adam do first? He names everything. I’m doing the reverse—I’m un-naming everything!” His nominal aphasia may be linked to a recent stroke. At the time, Gilliam didn’t realize it was a stroke; he thought he was losing his sight and shares a funny story about walking into an invisible man.

Our next destination is the London Coliseum on St Martin’s Lane. Our journey is organized by location rather than chronology, so we’ve fast-forwarded to 2011, when Gilliam directed Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust here. “I know nothing about opera,” he admits. “I’d probably seen one or two at most in my entire life.” Still, he was convinced to take on the project. He set Faust in Nazi Germany but had to soften the portrayal when the show moved to Berlin. “They were very uneasy about Faust in hell with Hitler so prominently featured.”

The security guard is hesitant to let us in. Perhaps he doesn’t believe that this man with a rat-tail haircut and a worn patchwork jacket once directed an opera here. While phone calls are made to sort it out, Gilliam says, “I can show you a good spot to take a leak,” and ducks down an alley.

Ugh. Yes, it smells. Thankfully, we don’t contribute to the odor; Gilliam just wants to point out a slice of authentic London. It’s a stark contrast to the lavish Edwardian grandeur of the Coliseum’s interior, which we eventually get to see. His production of Faust was a hit. “I was so proud—and 41% of the audience had never been to an opera before. They showed up in jeans. My happiest moment was on the last day when a fight broke out in the ticket line! I thought, ‘Yes, we’ve made it!'”

On our way to the final stop, Gilliam describes his life as a fairy tale. “There’s the king and knights doing their thing, the lovely virtuous maiden who’s always getting kidnapped, and witches lying in wait. It’s all there.”

His last film, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, took 25 years to complete because he kept running out of funding. “Then my daughter met a woman who had recently come into a fortune late in life. She had been following my career—or lack thereof—and she gave us three and a half million euros, just like that. A Fairy Godmother entered our lives. ‘You’re going to the ball, Terry!'”

We don’t end up at a ball but at a pub, the Horseshoe in Clerkenwell, where in 2008 Gilliam filmed a scene for The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus. The movie follows a traveling theater group whose leader, played by Christopher Plummer, is both wise and childlike, with more than a touch of Gilliam in him. Gilliam says he relates more to Don Quixote. “It’s about a man who sees reality in a nobler, more beautiful way, constantly failing and being knocked down, but you keep getting back up. That’s the challenge.”

Richard, the pub’s landlord, welcomes Gilliam warmly and has fond memories of when Doctor Parnassus’s peculiar troupe came to town. But a shadow hangs over the project: Heath Ledger also starred in the film—it was his last. Gilliam wants to show me where they had their final conversation and leads me to the men’s restroom. “So I’m here, having a piss, and Heath comes in and stands over there,” he says, pointing to the other end of the urinal. “I’m happily going about my business, and h—”He said, “Terry.” I turned around, and he was wearing this ridiculous mask and clown makeup. He said, “We’ve got to stop meeting like this.” What a place to say goodbye.

Two days later, Ledger was dead. He had accidentally overdosed on prescription drugs in his New York apartment. He was only 28, though Gilliam always thought he seemed much older. “Everyone who knew him said there was a very old soul inside that young body. There was no doubt he was going to be the finest actor of his generation. He had it all, and everyone loved him because he had such warmth. His magnetism worked on so many levels—he was incredibly smart and capable of everything you could ever want from an actor.”

Later, while Gilliam was in Vancouver filming the Imaginarium scenes—a mirror that lets people step into their own imaginations—he received the call about Ledger. “I just wanted to die,” Gilliam recalls. His first instinct was to abandon the project, but he was convinced to continue. They used the footage they already had of Ledger and brought in three of his friends—Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell, and Jude Law—to play transformed versions of his character. The film is dedicated to Ledger.

When asked if he ever thinks about his own death, Gilliam replied, “I’m not worried about it at all. Of course, I think about it every day, but in fun ways. I just don’t want anyone in my family to jump the queue—I’m going first, number one.” He has a plan laid out in his will. They own a house in Italy, perched like a nipple on a breast-shaped hill in Puglia. “I want to be buried there with the best view. Put me in the ground in a cardboard coffin, then plant an oak sapling in my chest so I can grow into an oak tree. It’s beautiful.”

And it is beautiful—perhaps a little inappropriately so, which feels fitting. Maybe a giant foot will come along and stomp on it someday…

Filmmaker and Monty Python veteran Terry Gilliam will be interviewed at a special Guardian event on October 29th, celebrating his extraordinary life and 50 years in film. The event will be held live at Cadogan Hall in London and streamed online. Book tickets through the provided link.

This article was updated on October 21, 2025. An earlier version included a photo from the set of The Brothers Grimm in a section discussing The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus. That image has been replaced.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about I bid farewell to Heath Ledger at this very urinal a walk through Terry Gilliams key locations

General Beginner Questions

Q What is this walk through Terry Gilliams key locations about

A Its a guided tour or selfguided walk that takes you to reallife film locations in cities like Prague and London focusing on movies directed by the iconic filmmaker Terry Gilliam

Q What does the phrase I bid farewell to Heath Ledger at this very urinal mean

A Its a memorable and quirky quote referring to a specific locationa public urinal in Praguewhere Terry Gilliam said a personal goodbye to the actor Heath Ledger during the filming of The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus

Q Which Terry Gilliam movies are typically featured on this walk

A The walk primarily focuses on locations from The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus but it often includes sites from his other famous films like 12 Monkeys and The Brothers Grimm

Q Where does this walk take place

A The walk is centered in Prague Czech Republic as it was a major filming location for several of Gilliams films

Q Do I need to be a hardcore Terry Gilliam fan to enjoy this

A Not at all Its a great activity for film lovers in general fans of unique architecture and anyone who enjoys exploring a city from a different creative perspective

Advanced Detailed Questions

Q Why is the urinal location so significant

A It marks a poignant moment in film history Heath Ledger passed away during the production of Doctor Parnassus and this spot was one of the last places Gilliam saw him during filming making it a touching if unusual memorial

Q Besides the urinal what are some other key stops on this tour

A Other stops often include the Charles Bridge and Kampa Island the bar where Ledgers character first appears in Parnassus and various Gothic and Baroque buildings that provide the perfect Gilliamesque backdrop