In 1982, artist Agnes Denes planted a two-acre wheat field on an empty lot in New York’s Battery Park, close to the newly built World Trade Center. The skyscrapers towered over the golden crop, creating a scene that seemed lifted from Andrew Wyeth’s pastoral painting, Christina’s World. Her work, Wheatfield: A Confrontation, challenged what she described as a “powerful paradox”—the existence of hunger in a world of plenty.

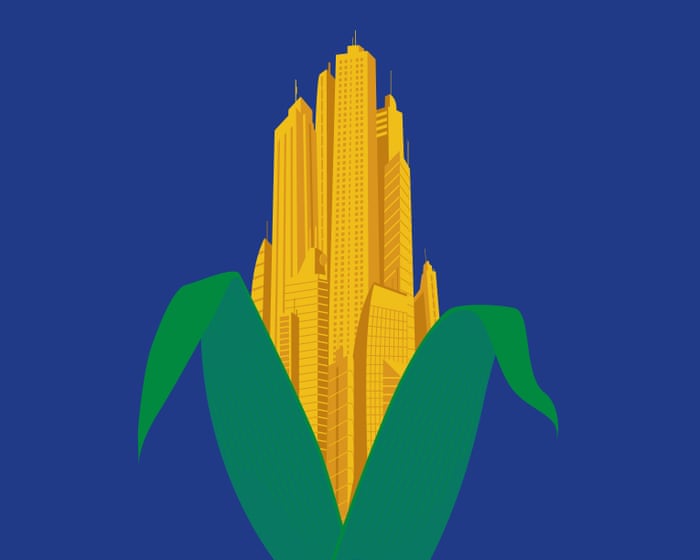

Back then, the global population was 4.6 billion. By 2050, it’s expected to more than double, raising serious questions about how we will feed everyone. Already, 2.3 billion people face food insecurity. The Covid-19 pandemic and extreme weather have exposed how fragile our food systems are. Denes was seen as ahead of her time for highlighting ecological issues decades before they entered public consciousness. She may also have been prophetic in anticipating how we would grow food. With over two-thirds of the global population projected to live in cities by 2050, can urban farming help feed 10 billion people?

Urban agriculture includes everything from high-tech vertical farms and soil-free methods like hydroponics and aquaponics, to informal community gardens on unused urban land. It’s not a new concept: during both World Wars, “victory gardens” helped supplement food rations. In the 1970s and 80s, “green guerrillas” cultivated hundreds of vacant plots across Manhattan. By the 1990s, the United Nations recognized urban farming as vital to development. Even during the Syrian civil war, residents in besieged eastern Ghouta grew mushrooms in their basements.

The pandemic sparked a short-lived boom in urban farming, with $4.5 billion invested in vertical farming startups in 2021. Many of these ventures failed as lockdowns ended, suggesting the trend had peaked. But the idea persists. In January, the Scottish government opened a new $1.8 million Vertical Farming Innovation Centre. Farms are now thriving in Brooklyn shipping containers, Paris underground car parks, London’s WWII bomb shelters, and on rooftops from Hong Kong to Singapore. Already, urban agriculture supplies 5–10% of the world’s legumes, vegetables, and tubers.

Urban farming could improve diets in wealthier nations and increase calorie availability in developing regions. A 2025 study suggests it could help achieve several UN Sustainable Development Goals related to hunger, sustainable cities, and responsible consumption. It would also shorten vulnerable supply chains and reduce the carbon emissions linked to transporting and packaging food. A 2013 study found that food grown in London generated 2.23 kg less CO₂ per kilogram compared to conventional agriculture.

Soil-free farming eases pressure on overused land and water systems. Vertical farming can use up to 98% less water than traditional methods, according to the World Economic Forum. Rainwater can be collected from rooftops, and urban wastewater—even treated “black water”—can be recycled for its nutrients. Because these are closed-loop systems, they don’t pollute rivers.

Green roofs also help cool buildings, reducing the urban heat island effect. And by growing their own food, communities gain independence from industrial agriculture—especially important in underserved areas. Cultivating food is a fundamentally human activity. Shifting from being only consumers to also becoming producers can empower communities and enrich lives.

Still, urban farming isn’t a perfect solution. Open-air plots near roads can absorb pollutants, while indoor farming is energy-intensive. A 30-story vertical farm covering five acres could yield as much as 2,400 acres of traditional farmland, year-round and unaffected by climate—but scaling this globally would require unsustainable amounts of energy.

A mixed approach wouldEnergy-intensive hydroponic indoor farms are ideal for Gulf states, which import 85% of their food and have limited freshwater but abundant renewable energy. In other regions, low-impact farming on urban fringes, though less productive, would be more appropriate. As highlighted in this paper, “nature connectedness”—the closeness of our relationship with other species and the wild—has dropped by 60% since 1800. Agroecology, a holistic approach to growing food, could help reverse this trend. Defined by principles like adapting to the local environment, building healthy soils, protecting biodiversity, and minimizing external inputs, it could turn street corners and vacant lots into sources of food.

Just a mile from my home in Edinburgh, Lauriston Farm is an agroecology cooperative transforming 100 acres of former sheep pasture into a vibrant mix of market gardens, community allotments, agroforestry (where crops grow alongside trees to enhance soil and yields), orchards, and restored wetlands and meadows. Similar to Denes’s Wheatfield, crops here flourish in the shadow of tall buildings—apartments rather than skyscrapers—making it one of the city’s most quietly revolutionary spaces.

Lauriston Farm alone can’t feed the entire city, but small efforts combined can yield significant results. Worldwide, small farmers produce between a third and half of our calories without resorting to the harmful, high-yield methods of industrial agriculture. Agroecology has the potential to reshape not only where our food comes from but also our connection to nature. Its principles should be woven into municipal and economic planning, blending green and gold with the urban grey. However, gaps in national and local policies pose challenges. We need to map edge lands, make unused land accessible, and provide investment and training to help communities start growing.

Urban agriculture won’t single-handedly feed 10 billion people, but it’s too important to overlook. We must reduce food waste, protect soils, curb pollution, address climate change, and safeguard biodiversity, especially pollinators. As Derek Jarman wrote in Modern Nature, “My garden’s boundaries are the horizon.” Every small change expands what we believe is possible.

David Farrier is the author of Nature’s Genius: Evolution’s Lessons for a Changing Planet (Canongate).

Further reading:

– Urban Jungle: The History and Future of Nature in the City by Ben Wilson (Vintage, £12.99)

– Wild Cities: Discovering New Ways of Living in the Modern Urban Jungle by Chris Fitch (William Collins, £22)

– Sitopia: How Food Can Save the World by Carolyn Steel (Vintage, £10.99)

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of helpful and clear FAQs about whether urban farming can feed the global population

Beginner Definition Questions

1 What exactly is urban farming

Urban farming is the practice of cultivating processing and distributing food in or around cities and urban areas This can include rooftop gardens community plots balcony containers vertical farms and even indoor hydroponic systems

2 Can urban farming really feed the entire world

On its own no Urban farming is not a single solution to global hunger Its primary strength is in supplementing the global food supply increasing food security in cities and providing fresh local produce The vast majority of staple crops like wheat corn and rice will still need to be grown on largescale rural farms

3 What are the main benefits of urban farming

Fresh Local Food Reduces food miles and provides access to nutritious ripe produce

Food Security Makes cities more resilient to supply chain disruptions

Green Spaces Improves air quality reduces the urban heat island effect and creates community hubs

Reduced Waste Composting food scraps can turn waste into fertilizer

Practical HowTo Questions

4 I live in an apartment Can I still participate

Absolutely You can grow herbs leafy greens and small vegetables in pots on a sunny windowsill balcony or under grow lights Methods like container gardening and small hydroponic kits are perfect for small spaces

5 What are the easiest crops to grow in a city

Beginnerfriendly crops include lettuce kale spinach radishes herbs green onions and cherry tomatoes They dont require a lot of space and have relatively short growing times

6 How can I start a small urban farm

Start small Choose a sunny spot get some containers with good drainage use quality potting soil and pick easy plants you love to eat Many communities also have gardening groups that can offer advice and support

Advanced Critical Thinking Questions

7 What are the biggest challenges or limitations of urban farming

Space Cities are crowded making it hard to find large contiguous areas for farming

Cost Setting up advanced systems like vertical farms can be expensive