At just 18, Gianni Infantino made his first run for office in a presidential election at FC Brig-Glis, the local amateur football club in his small Swiss hometown. Competing against two older men and lacking any notable football background, the freckled, red-haired teenager was the clear underdog. Yet he possessed a clear vision, relentless drive, infectious energy, and strong ties within the town’s Italian immigrant community. Even at that young age, he had a knack for bold ideas. To the surprise of club veterans, Infantino won—partly by vowing to bring in new sponsors and revenue, and partly by offering something more concrete: if elected, his mother Maria would wash all the players’ kits every week for as long as he remained president.

This early episode sheds light on two key traits of the current FIFA president. First, it revealed an ambition so grand it might seem delusional, were he not so skilled at turning it into reality. Second, it highlighted his unique talent for cutting through bureaucratic jargon and appealing to our most basic, transactional instincts. Still a teenager with the odds stacked against him, Infantino had already grasped a fundamental rule of politics: everyone, no matter their status, has “dirty laundry” they’re eager to offload.

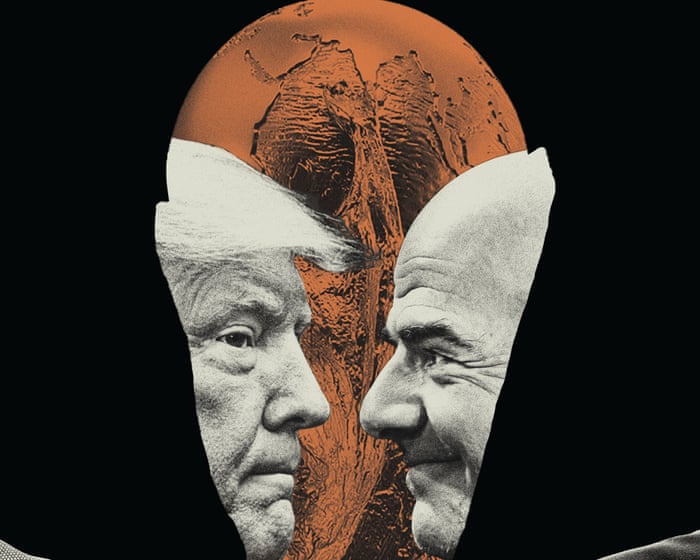

Now picture a gathering of world leaders: Donald Trump chatting animatedly, Egypt’s beaming Abdel Fattah al-Sisi beside him, then Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, with Keir Starmer behind. Next to Starmer stands Friedrich Merz, ahead of him Emmanuel Macron, and beside Macron, Indonesia’s Prabowo Subianto. A few spots over—in the back row but craning his neck as if unwilling to be there—is Infantino, the only attendee at the Sharm El-Sheikh peace summit without an official political role.

So why was he there? How did an organization best known for drawing football teams from hats secure a seat at a conference shaping the Middle East’s future? Despite the gravity of the occasion, Infantino hardly hid his delight at the invitation. He posed for photos with world leaders, pledged to rebuild Gaza’s football infrastructure, created content for his Instagram, and revealed that President Trump had personally requested his presence.

Infantino (far right in the photo) at the Sharm El-Sheikh peace summit in October this year. Photograph: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Though he often claims football can’t solve the world’s political issues, Infantino spends considerable time with politicians. During the Covid pandemic, he traveled to Washington for the signing of the Abraham Accords, which normalized relations between Israel and two Arab nations. He’s kicked a ball around the Kremlin with Vladimir Putin and attended a heavyweight fight with Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed bin Salman. But his closest bond appears to be with Trump, a relationship years in the making. Infantino was prominent at Trump’s second inauguration this year and has been a regular guest at Mar-a-Lago and the Oval Office. In December 2024, Ivanka Trump conducted the draw for FIFA’s new $1 billion Club World Cup, held in the U.S. this summer. Then in July, FIFA opened a New York office in Trump Tower, making the world’s top sports governing body an official tenant of a company owned by the sitting U.S. president.

He assured Trump that they would “make not just football, but everything, great again.”Infantino claims that his close ties with the co-host of next summer’s men’s World Cup—an event that generates over 80% of FIFA’s revenue—are just part of his job. Yet, this mutual admiration goes far beyond typical flattery. In contrast, Kirsty Coventry, president of the International Olympic Committee overseeing the 2028 Los Angeles Games, has not appeared publicly with Trump since her election nine months ago.

Infantino’s relationship with Joe Biden was much more distant. They met briefly at a 2022 G20 summit, and Infantino later visited the White House in 2024 for an hour-long meeting with National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan. He has also spent little time with the leaders of Canada and Mexico, the other co-hosts, and notably refrained from adopting their campaign slogans. Instead, he told Trump in January that they would “make not only America great again, but also the entire world.”

FIFA’s ethics code mandates political neutrality, and some officials privately worry about Infantino’s apparent closeness to Trump, who is widely criticized for his harsh rhetoric, immigration policies, and authoritarian tendencies. By echoing Trump’s slogan, Infantino appears to endorse his politics. As a skilled communicator fluent in six languages and highly aware of his public image, it’s unlikely this was an accident. How does this align with FIFA’s motto, “Football Unites the World,” when he openly courts one of the most divisive leaders? Is this mere realpolitik to please a key partner, or does it signal a deeper ideological alignment?

Football’s appeal lies in its unpredictability and thrilling narrow margins, but its politics often involve fixed outcomes and deal-making. Since becoming FIFA president in 2016, Infantino has been re-elected unopposed in 2019 and 2023, following the old adage that you can only beat what’s put in front of you.

On December 5, the 2026 World Cup draw will take place at Washington’s Kennedy Center, which has recently seen a cultural takeover by Trump and his allies, with Trump himself as board chairman. At the event, Infantino will present the first FIFA Peace Prize to honor those who “unite people and bring hope for future generations.” If Trump doesn’t win, it would be more surprising than any upset in next summer’s 104 World Cup matches.

Nick McGeehan of FairSquare notes, “Infantino is a symptom, not the problem. His role isn’t to sustainably govern the game but to accumulate power and money, redistributing it to associations. If grassroots development happens, that’s a bonus, but it’s not the core focus.”

Infantino succeeded the disgraced Sepp Blatter when FIFA’s reputation was at its lowest, taking over an organization shaken by corruption scandals and losing sponsors and allies.Zurich faces two interconnected yet often conflicting objectives: restoring FIFA’s reputation and rebuilding the financial foundation that supports the global game played in every country worldwide—a foundation that also underpins Infantino’s authority.

The 211 members of the FIFA Congress hold the power. They convene annually, elect a new president every four years, and allocate development funds essential for maintaining and expanding the sport. Unsurprisingly, the distribution of these funds has always been the organization’s central focus. Blatter’s FIFA eventually crumbled under the weight of its own corruption—a system of extravagant and often illegal personal enrichment that benefited only a select few at the top.

During his presidential campaign, Infantino told delegates, “FIFA’s money is your money, not the president’s money,” sparking thunderous applause.

Infantino’s popularity within FIFA hinges on maximizing revenue. This explains the expansion of the men’s World Cup to 48 teams in 2026, a model the women’s tournament will follow in 2031. It also accounts for FIFA’s new Club World Cup, won by Chelsea in its inaugural edition this summer, which aims to tap into the overwhelming success and revenue of club football, which consistently outperforms international competitions. However, this revenue drive has led FIFA into controversial partnerships.

In a way, Infantino’s masterstroke has been to shield FIFA from accusations of secret dealings by conducting power plays openly. The World Cup has long been a stage for autocratic regimes, from Mussolini’s Italy in 1934 to Argentina’s military dictatorship in 1978. The selections of Russia and Qatar for the 2018 and 2022 tournaments, marred by voting scandal allegations, predated Infantino’s tenure. By operating transparently, he has deflected some criticism.

Last December, the 2034 men’s World Cup was uncontestedly awarded to Saudi Arabia, a nation with which Infantino has cultivated close ties. Saudi money, channeled indirectly through a costly broadcast deal, helped fund the Club World Cup. FIFA assessed Saudi Arabia’s human rights record as a “medium risk” in its bid evaluation—a verdict Amnesty International called an “astonishing whitewash” of the country’s labor rights abuses.

Rather than avoiding controversy, Infantino often confronts it head-on, framing powerful regimes as victims of Euro-centric bias. On the eve of the 2022 Qatar World Cup, he delivered a remarkable speech accusing critics of colonial attitudes and positioning himself as a defender of the oppressed. “Today I feel Qatari,” he declared. “Today I feel Arab. Today I feel African. Today I feel gay. Today I feel disabled. Today I feel like a migrant worker. I understand them because I know what it’s like to be bullied—for having red hair, freckles, and being Italian.”

While no one has ever been enslaved or denied rights for having freckles, Infantino’s background sheds light on his rapid ascent. Born in 1970 to Italian immigrants—a railway worker father and a mother who ran a station kiosk—he first experienced football in local teams.He had little success. “Let’s just say he wasn’t the best player,” his cousin Renato Vitetta once remarked. Even in primary school, he had abandoned his dream of becoming a footballer, writing in a school assignment that he aimed to become a football lawyer instead.

His election as president of FC Brig-Glis marked the beginning of his career in football governance. After finishing his law degree at the University of Freiburg, he joined UEFA, Europe’s football governing body, in 2000 and rose to become its secretary-general in 2009. For years, European football fans knew him as the man in charge of the Champions League draw: the bespectacled Swiss technocrat methodically explaining the pots and rules, introducing much more famous personalities to carry out the actual draw.

However, when Sepp Blatter’s presidency fell apart, Infantino’s ambitious side resurfaced. UEFA president Michel Platini was initially favored to succeed Blatter, but after both faced allegations of improper payments (for which they were later cleared), it was Platini’s protégé who emerged as Europe’s candidate—a fresh face representing a clean break. Still, his eventual win over Jordan’s Prince Ali bin Hussein came as a major surprise, credited to his relentless campaigning and the crucial role played by U.S. Soccer president Sunil Gulati in swaying votes between the first and second rounds.

Once again, Infantino had overcome expectations. Those who knew him in his early years describe a quiet, unassuming man, not particularly charming or charismatic, and deeply focused on procedures and details. However, colleagues who have worked closely with him depict a more complex figure, someone who can shift effortlessly from casual dad jokes to intense seriousness. While Blatter kept a bed next to his office for afternoon naps, the workaholic Infantino replaced it with exercise equipment.

This may explain why Infantino appears so at ease among the wealthy and powerful. This is his world, his destiny—the freckled boy from Brig who made it to the top. FIFA employees in Zurich have noted his abruptness and impatience, traits of someone focused on results with little tolerance for delays or hurdles. Longtime French-speaking staff were quietly instructed to address him formally as “vous” instead of the informal “tu.” The Swiss newspaper 24 Heures quoted an associate who described Infantino as aloof, often seen in the smoking area lighting a cigarette while staring at his smartphone.

Yet, in influential circles, he comes alive. Infantino has a natural talent for identifying the most powerful people in any room and tailoring his approach entirely to them. Despite starting his presidency by promising to fly budget airlines, he now spends much of the year traveling the world on private jets. As an anonymous source told Politico, “He loves dictators and billionaires. When he sees people with money, he melts.”

This comfort with the elite seems to define him. “He clearly thinks of himself as a statesperson,” says McGeehan. “If you don’t believe power can be challenged, you start acting like an authoritarian and feel at home among others with similar power. Is it ideological? I don’t think so. I believe he’s ultimately quite a weak man.”

In May of this year, Infantino was in the White House East Room for a World Cup taskforce meeting with figures including Donald Trump and Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem. During the event, he received news that his beloved Inter Milan was mounting a comeback against Barcelona in the Champions League semi-final. For thIn the final 15 minutes of the game, he sat on the sidewalk of Pennsylvania Avenue, watching football on his phone, completely absorbed.

Even Infantino’s harshest critics acknowledge that the FIFA president is a true football fanatic, an unapologetic advocate for the sport and its ability to unite people. Those close to him say he has no other interests, rarely discusses other sports, and doesn’t seem to enjoy art or music. When he describes football as an “investment in happiness” and promotes it as a force that can end conflicts and bring people together, there’s a sincere, if misguided, belief behind his words.

This highlights the central contradiction of Infantino: a man leading the world’s most popular sport is also actively damaging it. The Club World Cup was created despite protests from the global players’ union, Fifpro, which warned that adding another tournament to an already packed schedule would harm players’ well-being. FIFA responded by ignoring Fifpro and seeking approval from smaller organizations that Fifpro calls “fake unions.”

Infantino’s approach can be summed up as currying favor with the powerful while neglecting the vulnerable. He indulges world leaders but sidelines those who need his help most. Rights groups have criticized his inaction toward Iran’s football federation for continuing to limit women’s access to games. A complaint from the Palestinian football federation about Israeli teams from illegal West Bank settlements playing in their league has gone unresolved for over two years.

Meanwhile, Infantino’s efforts to win over Trump continue unabated. Trump had little interest in football until a 2017 call with Infantino, who convinced him that the sport offered access to the world’s largest captive TV audience. Their friendship thrives on Infantino’s ability to appeal to Trump’s baser instincts, such as when he jokingly gave him red and yellow cards to use on the press during a 2018 Oval Office meeting.

In return, FIFA is set for its biggest financial windfall ever. Due to dynamic pricing, the most expensive ticket for next summer’s World Cup will cost nearly five times the equivalent in Qatar 2022. Parking for the final in New Jersey will be $175 per space. All this revenue will be tax-free, flowing directly into FIFA’s accounts and reinforcing Infantino’s power by funding member organizations. For an organization that only profits once every four years, his alliance with Trump isn’t just personal—it’s a business necessity.

It’s fitting that both Trump and Infantino rose to power in 2016, a year that now seems to mark the start of a new era in global politics, defined by boldness and shamelessness. Like Trump, Infantino refuses to be constrained by history. Instead, he aims to shape it, acting as a vocal and reactive leader, constantly promoting and selling, ruthless toward opponents and driven by financial motives—a worldview where a person’s value is tied to their spending power.

Traditionally, only World Cup winners are allowed to touch the trophy. But during an August visit to the White House, Infantino made an exception for Trump. The president held the cup in his small hands, fumbled with it, called it a “beautiful piece of gold,” and then asked if he could keep it. This moment serves as a metaphor for football itself and the men who hold it in their grasp.It was as good as any.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about Gianni Infantinos alignment with the US president designed to be clear and informative

General Beginner Questions

1 Who is Gianni Infantino

Gianni Infantino is the President of FIFA the international governing body for soccer

2 Why is this alignment a big deal

Because FIFA is a global nonpolitical sports organization and aligning with any single world leader especially a divisive one can be seen as taking a political side which goes against its mission to unite the world through sport

3 What does appealing to Trumps most basic impulses mean

It means using language and tactics that resonate with Trumps wellknown political style such as emphasizing nationalism economic deals and a confrontational approach to existing international agreements

4 What specific things has Infantino done or said to show this alignment

He has publicly praised Trumps leadership echoed his America First rhetoric by talking about putting FIFA first and sought his support for major events like the 2026 World Cup which the US is cohosting

Strategic Advanced Questions

5 What are the potential benefits for FIFA in this relationship

Political Leverage Gaining support from a powerful nation to smooth the path for major tournaments like the 2026 World Cup

Economic Gains Appealing to the massive US market and American corporate sponsors to increase revenue

Influence Aligning with a leader who challenges the status quo could help FIFA reshape international sports politics to its advantage

6 What are the main criticisms or risks of this alignment

Damaging FIFAs Image It undermines FIFAs claim of being a neutral unifying force and alienates large portions of the global soccer community who disagree with the political stance

Hypocrisy FIFA has rules against political interference in member associations so its president engaging in highlevel politics appears hypocritical

Reputational Risk Tying the organizations brand to a volatile political figure makes it vulnerable to shifts in that leaders popularity and legacy

7 Is this just about the 2026 World Cup

While securing a successful 2026 World Cup is a major immediate goal the alignment is also about longterm strategyexpanding soccers commercial and cultural