On the day before Christmas Eve, just as France was settling into the holiday lull, something jolted me out of any festive calm. The satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo—globally and tragically known for being targeted in a 2015 Islamist attack—published a caricature of me. It was appallingly racist.

The cartoon showed me with a huge, toothy grin and an enormous mouth, dancing on a stage before an audience of laughing white men, wearing only a banana belt over a largely exposed body. The headline read: “The Rokhaya Diallo Show: Mocking secularism around the world.”

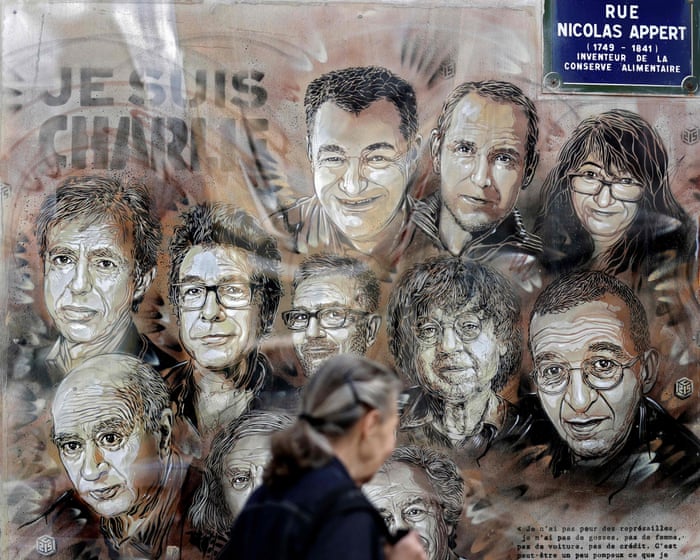

Stunned by the violence of this grotesque image, I shared it on social media with a brief analysis: “True to slave-era and colonial imagery, Charlie Hebdo once again shows it cannot engage with the ideas of a Black woman without reducing her to a dancing body—exoticized, supposedly savage—adorned with the very bananas thrown at Black people who dare to enter public life.”

The reference to Josephine Baker was as obvious as it was disrespectful and baffling. One of the most iconic performances by the American-born dancer, actress, and activist in the 1920s featured Baker in a (rubber) banana skirt, at a time when France proudly displayed what it saw as its superiority over its colonial empire. But Baker was far more than that act, whose erotic charge she deliberately subverted through exaggerated, clownish gestures. She was a member of the French Resistance, received France’s highest military honors, was the only woman to speak at the 1963 March on Washington led by Martin Luther King Jr., and is the only Black woman interred in the Panthéon, France’s national mausoleum for its greatest figures. I was dismayed to see her legacy reduced to a grotesque, minstrel-show grimace.

From the moment I posted my reaction, the controversy exploded. Millions of views poured in across my social media, along with outraged responses and analytical content in several languages unpacking the image’s colonial undertones. I received a level of attention and support I never imagined when I first shared my disgust.

But instead of acknowledging the obvious racism, Charlie Hebdo resorted to the clumsiest form of gaslighting. The magazine responded to the wave of protests by accusing me of “manipulation”—supposedly a tactic I knew well—claiming I had “distorted” the image by presenting it “separated from its text.” As if any accompanying article could justify such despicable imagery.

The article in question calls me “America’s little sweetheart,” operating from foreign platforms like the Guardian to smear what it calls “my country of birth”—a phrasing that, to me, insinuates I am not fully French. As a Black Muslim woman, I know that any public criticism of France is often read by racists as betrayal by an ungrateful immigrant’s daughter. Yet even setting aside this poisonous framing, the article offers no coherent link—political, historical, or symbolic—to Josephine Baker. It has absolutely nothing to do with her, or with bananas.

The most absurd part is Charlie Hebdo’s conclusion, where the magazine claims to be “an anti-racist, feminist, and universalist newspaper”—which, in its view, is what I “blame” it for. In a move France has perfected, an all-white editorial team defends a racist cartoon drawn by a white man by turning the accusation back on the Black victim—an author of some 20 books and documentaries on race and gender—branding her as hostile to anti-racism and feminism. It would be funny if it weren’t so pathetic.

In my message denouncing the drawing, I also wrote, “this hideous cartoon is meant to remind me of my place in the racial and sexist hierarchy,” because I understood exactly what lay behind this device. Stripping me and placing me in…A humiliating posture is a way of discrediting me as a legitimate voice, of reminding me of the fate forced upon my ancestors, whose humanity was denied.

Josephine Baker made her dancing debut in Paris at 19. By her death in 1975, she had become a film actor, the world’s most photographed woman, a pilot, a spy for France—the nation she embraced—and an anti-racist activist, among many other roles. Yet Charlie Hebdo proved incapable of invoking her in any way except by reducing her to a naked body dressed in colonial costume.

What matters here is this: our paths have little in common. The choice to link me to a 19-year-old woman (I am 47) who rose to fame a century ago in a field unrelated to mine reveals how white supremacy treats Black women as interchangeable.

This controversy is not only about me, but about all of us who daily face misogynoir—the blend of sexist and anti-Black violence named by scholar Moya Bailey—that targets any Black woman who dares to step beyond the secondary role postcolonial societies still try to impose on her.

Charlie Hebdo sought to punish a woman it considered too bold, and a Black person who does not depend on the French media to be heard. It is no coincidence that among the thousands of messages of support I received—including one from the historic Ligue des Droits de l’Homme—was one from former French justice minister Christiane Taubira, the first Black woman to hold that post in 2012.

Taubira herself endured some of the most vicious racist attacks, including a vile Charlie Hebdo cartoon. With the eloquence she is known for, she described the drawing as “intellectually impoverished, visually flat, stylistically bland, semantically mediocre, and psychologically obsessive.”

By trying to discredit me as a legitimate participant in public debate, Charlie Hebdo has also exposed its refusal to engage as an equal. In seeking to humiliate me, the magazine has stained itself—and degraded the very freedom of expression it once symbolized.

Rokhaya Diallo is a French journalist, writer, film-maker and activist.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs addressing the complex relationship between satire offense and free speech in the context of an experience with Charlie Hebdo

Understanding the Core Issue

Q1 What is Charlie Hebdo and what is its purpose

A Charlie Hebdo is a French satirical weekly magazine known for its provocative cartoons and commentary Its stated purpose is to critique and mock all forms of power authority and dogmaincluding religion politics and ideologyusing humor and often extreme satire

Q2 I felt personally humiliated by a Charlie Hebdo cartoon Doesnt that cross a line

A It can certainly feel that way Satire often works by exaggeration and ridicule and when it targets beliefs or identities you hold dear it can feel like a personal attack The magazines defense is that it is attacking ideas and institutions not individuals though this distinction can be painfully thin for those affected

Q3 If Charlie Hebdos satire hurt me how can it claim to represent freedom of speech

A This is the central tension Freedom of speech protects the right to express ideas even those that are offensive or hurtful Charlie Hebdo argues that to have meaningful free speech it must include the right to criticize and offend From their perspective avoiding offense would mean selfcensorship which undermines the principle Your experience highlights the conflict between the right to offend and the impact of offense

The Conflict Free Speech vs Harm

Q4 Isnt there a difference between free speech and hate speech

A Legally this varies by country In France and the US hate speech laws are much narrower than many assume They typically require speech to directly incite imminent violence or discrimination Charlie Hebdos satire however offensive has generally been defended by courts as politicalsocial commentary not as a direct call to violence which places it in the category of protected speech

Q5 By publishing things that deeply offend religious groups is Charlie Hebdo creating a harmful environment