Marc Brew was in the back seat of a car on a Johannesburg motorway, laughing and sharing jokes with friends, when a pickup truck suddenly appeared, speeding toward them on the wrong side of the road. “Out of nowhere, I just remember seeing this white flash,” says Brew, who was 20 at the time. The truck—driven by someone later found to be drunk—slammed directly into their car. Brew was the only survivor; everyone else in the vehicle died.

Nine months earlier, Brew had moved from Australia to South Africa to join the Pact ballet company in Pretoria. That Saturday, after his usual morning dance class, he and his friend Joanne—also a company member—set off with her brother Simon and Simon’s fiancée’s brother, Toby, heading for a game reserve where they planned to go bush walking. When the truck hit, “it was like time froze,” recalls Brew, now 48. “I remember my ears were ringing really loud, like I’d been at a concert.”

Joanne had fallen from the seat beside him and lay at his feet. In the front, Brew saw Simon slumped over the steering wheel and 16-year-old Toby on the dashboard. “I was trying to yell out to them, but I didn’t know if I was making any sound. I just couldn’t move. And I remember my neck was hurting,” he says. “Then I must have lost consciousness.”

When Brew came to, he felt pain in his neck and gravel pressing into the back of his head—he had been moved to the roadside. Hearing voices around him on the hot day, he thought, “Well, I’m alive.” He saw shadows of people moving and heard someone say, “You’ll be OK.”

“Don’t worry about me—I’m fine,” he replied. “Just look after Joanne, Simon and Toby.” The image of them inside the car was still vivid in his mind.

He was rushed into an ambulance, then a helicopter. One thought raced through his mind before he blacked out again: “I’ve got to tell my mum.” Brew grew up in a single-parent household with his mother in a small rural town in New South Wales. She had always been his biggest supporter, enrolling him in his first dance class as a young child and, after he earned a scholarship to a dance boarding school in Melbourne at age 10, regularly making the eight-hour round trip to visit him.

The next thing he remembers is his mother being there. She and his aunt had flown from Australia—a difficult trip she arranged by securing an emergency passport, borrowing money for the flight, and arranging childcare for Brew’s two half-siblings. By the time they arrived, Brew had been in the hospital for two weeks, though he remembers nothing from that period. He later learned he had internal bleeding from the seatbelt’s impact during the crash (“but the seatbelt also saved my life”). Doctors packed him in ice to stop the bleeding, which worked, allowing surgeons to operate on his damaged organs. “My plumbing got reorganised a little bit,” Brew says. “Once I was stable from those internal injuries, they noticed my legs weren’t moving anymore.”

Although hospital records showed Brew could move his limbs when first admitted, his own memory is of waking up in a body he could barely control. At first, he couldn’t feel his legs, speak, or use his arms—abilities that slowly returned. “I remember seeing my body and I didn’t recognise it,” he says.”My feet were swollen and wouldn’t move—nothing would move. It felt completely foreign,” he says. As a dancer, he was accustomed to being in sync with his body, but now that connection was severed.

A CT scan revealed a spinal cord injury at his neck, leaving him paralyzed from the chest down. While in the scanner, he went into cardiac arrest and woke up to someone resuscitating him. This was one of several times in the hospital when Brew felt near death. “I remember sensations like sinking in my bed and fading into blackness,” he recalls. “I had to fight hard, almost like struggling to the surface for air, just to survive.”

For a few weeks, he avoided thinking about the chance that his feeling might never return. “I was in complete denial,” he admits. Accustomed to injuries and rehab from dancing, he thought, “It’s fine,” and was eager to return to Australia to begin rehabilitation and work hard.

That changed in what he calls “a horrible moment” when a doctor told him he was paralyzed, forcing him to face his future. “It felt like a movie scene where the doctor says, ‘Sorry, Mr. Brew, but you’ll never walk again,'” he says.

His first thought was, “That can’t be happening to me. I’m Marc, a dancer… I can’t not walk again.”

Around the same time, about a month into his hospital stay, Brew learned that his friends had died. He had suspected Simon and Toby were dead after seeing them in the car, but Joanne’s face was hidden by her hair. “For some reason, I thought Joanne would be okay,” he says—until her best friend visited and broke the news. Communicating with an alphabet board by blinking, he asked where Joanne was, and her friend pointed upward. At first, he thought she meant a higher floor, but then she said, “Joanne’s in heaven.”

Later, he asked about the other driver and was told the man survived with minor injuries, was arrested, and later jailed. Joanne’s parents, who had lost both their son and daughter, were so angry they couldn’t bear to see him, Brew says. Though therapy helped him let go of his anger, he never accepted the idea that “this happened for a reason,” as some religious friends suggested.

“Joanne, Simon, and Toby were loving, caring, funny people. Why were their lives taken, and why was mine left like this? I can’t see any reason for that,” he reflects.

Honoring his friends, Brew felt a heavy responsibility as the sole survivor. “I had to live for them too. No one told me to, but I felt it then, and I still do.”

After three months in a South African hospital, Brew returned to Australia, where he spent four more months in a rehab center. The flight was a “horrible, demeaning experience,” with otherPassengers stared down at him as he lay on a stretcher beneath the overhead luggage compartments. He came to dread public attention. After developing his motor skills and learning to use his wheelchair in the safety of rehab, Brew went on an outing to a shopping mall with some fellow residents. “Everyone stared at me because I was in a wheelchair, and it was just horrible,” he says. “That was really hard to deal with.”

At first, Brew struggled to accept his physical limitations and the help he now needed. “I was naive and stubborn,” he admits. “I didn’t want my nan to see me. I didn’t want my family to see me. I had always been the one making something of my life—the country boy who moved to the city to become a dancer.”

“I felt so exposed and didn’t want anyone to see me vulnerable like that,” he says. As he came to terms with needing help for basic tasks—like the time he had to ask his mother to help him bathe—”there were moments that were really, really low and dark.”

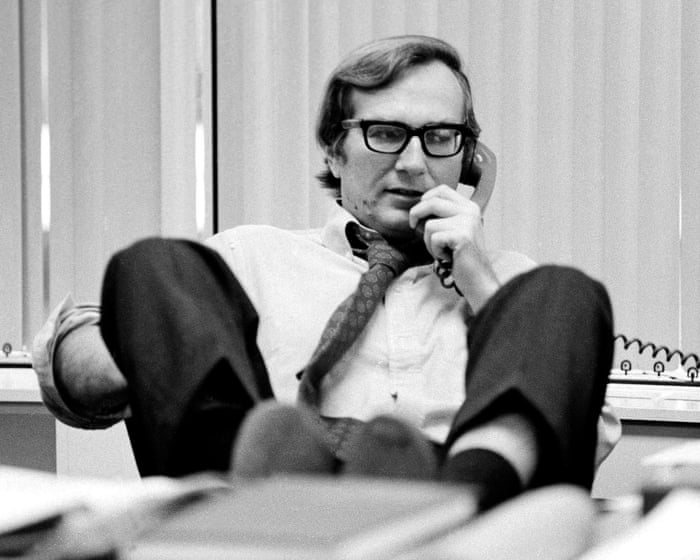

Yet through it all, “in my head, it was still me,” Brew says. “I still felt like Marc the dancer.” Two years after leaving rehab, he began dancing again after friends in the U.S. connected him with disability activist and dancer Kitty Lunn. Lunn invited Brew to visit her in New York, where he attended ballet classes and “rediscovered dance.”

The dance style he developed relies on incredible upper-body strength and precise control. Colin Hambrook, reviewing Brew’s 2015 show For Now, I Am… for Disability Arts Online, praised his “flawless, virtuoso dance skills,” noting that “slight movements of the fingers, hands, arms, torso, and head are full of intention.”

Sometimes Brew incorporates a wheelchair into his work, but not always. His most ambitious project to date is An Accident/A Life, a collaboration with choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui that tells the story of the car crash. For most of the performance, he moves across the stage using only his upper body, only introducing a wheelchair in the final five minutes. “Navigating from one scene to the next without the support of a chair is physically demanding,” Brew says—but it made sense for the story, since he didn’t have a wheelchair at the time of the crash. He also wanted to challenge audiences’ perceptions of disabled artists: “It made me think—when someone who doesn’t know me or the story sees me on stage, what do they think?”

Brew never expected to create a piece about the accident, but the performance is “not just about the crash,” he explains. “It’s about finding a life again.”

When he first returned to dancing after the accident, “I had to stop looking in the mirror because I’d get frustrated,” he says. “I wanted to get up and show everyone how to move and dance like I used to, and I couldn’t.” It took time for him to realize that “dance wasn’t about having beautiful legs, turnout, flexibility, or how high you jumped. Dance is about expressing myself through movement, and I could still do that.” Though his path was completely different from what he had originally planned—after a few years in South Africa, he had intended to move to the UK or the Netherlands to dance—he found a new way forward.Working with companies like Rambert and the Nederlands Dans Theater opened up new possibilities for him.

Nearly 30 years after the accident, Brew has danced and choreographed around the world. He moved to London in 2003 to join Candoco, a dance company that includes both disabled and non-disabled dancers. Today, he runs his own ensemble, the Marc Brew Company, based in Glasgow, where he lives with his partner, Matthew, and their two-and-a-half-year-old son, Jedidiah, who was born via surrogacy. Brew says Jedidiah is “the light of our lives.”

“My identity has shifted since the accident,” Brew reflects. “I’m a gay man, I’m a father now—I identify in many different ways.” He has reached a point where he feels empowered by his disability, though frustrations still arise. Sometimes he catches himself thinking, “I could just get up and do it, and it would be so much easier.”

When those thoughts come, he tells himself, “Marc, take a breath. You know you’ll find another way.” Being disabled has pushed him to be more creative and adaptable. “Things don’t have to be the way you think,” he says.

Brew has never accepted “no” as an answer. As a child, he kept dancing even when people told him he shouldn’t because he was a boy. Later, he met those who said he couldn’t dance because of his disability with the same determination. “How lucky am I?” he says. “I’m still able to do what I love—to dance, share, create, and perform my work for others. I get to be an artist, even though I was told I couldn’t.”

Marc Brew and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s show, An Accident/A Life, will be at Sadler’s Wells East theatre in London from 25–27 September.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs based on the scenario you provided written in a natural compassionate tone

Frequently Asked Questions

BeginnerLevel Questions

1 What should be my first step after such a devastating accident

Your first priority is your health Focus on your medical recovery and mental wellbeing Once you are stable its crucial to consult with a lawyer who specializes in wrongful death and catastrophic injury cases

2 What kind of lawyer do I need

You need a personal injury lawyer specifically one with experience in wrongful death and catastrophic injuries They understand the complex legal and financial implications of cases like yours

3 What is wrongful death

Wrongful death is a legal claim that arises when a persons death is caused by the negligent or intentional act of another In this case your friends families may have the right to file a wrongful death lawsuit against the drunk driver

4 Can I afford a lawyer

Most personal injury lawyers work on a contingency fee basis This means you dont pay anything upfront Their fee is a percentage of the financial settlement or award you receive so they only get paid if you win your case

5 What can I sue for

You can seek compensation for many things including

Medical bills

Lost wages and loss of future earning capacity

Pain and suffering

Emotional distress

Advanced Practical Questions

6 How do I prove the impact on my future ballet career

This requires strong evidence Your lawyer will work with medical experts vocational rehabilitation specialists and even your ballet instructors to document your preaccident potential and how your injuries permanently affect your ability to perform at a professional level

7 The driver was criminally charged Do I still need a civil lawsuit

Yes A criminal case is about the state punishing the driver A civil lawsuit is separate and is about obtaining financial compensation for you and the families of your friends for the losses you have suffered

8 What if the drunk driver doesnt have enough insurance

Your lawyer will investigate all possible sources of compensation This may include your own insurance policys