Led Zeppelin always carried an air of the forbidden. They were darker and more mysterious than other bands, and they rarely gave interviews—almost none at all. They famously despised Rolling Stone, and rumors swirled that Jimmy Page and Rolling Stone co-founder Jann Wenner had clashed over a woman in London. The magazine had panned their first album. Still, I had managed to interview them for the Los Angeles Times, which marked a sort of debut into the mainstream for the band. Two years later, as they prepared to release Physical Graffiti, their publicist Danny Goldberg invited me to join them on tour.

The key to getting Zeppelin on the cover of Rolling Stone was always going to be Jimmy Page. My plan was to interview the other members first, hoping that if Page still refused, Robert Plant would appear on the cover alone. I thought the idea of a solo cover might push Page to agree to a group shot—or he might shut the whole thing down, which seemed just as likely.

Back in San Francisco, Rolling Stone editor Ben Fong-Torres liked the idea and called daily for updates. I was already stretching the time I’d told my parents I’d be away, and I was skipping most of my classes at San Diego City College. Luckily, I’d convinced my journalism teacher to count the Zeppelin tour as class credit.

After shows, the band would head back to the Ambassador Hotel in Chicago before going out. To avoid fans, their rowdy road manager Richard Cole often took them to a gay bar around the corner—a tradition that lasted much of the tour. Fans searching the streets never guessed they could find Jimmy Page and Robert Plant dancing carefree to Gloria Gaynor or the Average White Band. I often slipped into restrooms to jot notes, sometimes hearing the sounds of cocaine use or sex from the next stall.

My interview with Plant went as planned. He was a true music lover, with taste that rivaled any critic or DJ. He could dive deep into a Jefferson Airplane record from years ago or introduce you to an unforgettable piece of obscure world music. Our conversation about Zeppelin was open and humorous. When I turned off my tape recorder, I felt confident it would all come together.

The shows kept coming, each one better than the last as the band grew more comfortable with their new material. Audiences instantly connected with future classics like “Ten Years Gone” and “Kashmir.” In Indianapolis, Page was polite but distant. By Greensboro, he began to ignore me, and soon he was looking right through me. He knew everyone else had spoken to me for a potential Rolling Stone feature. Time was running out—my parents were baffled by my extended absence, and I’d been on the road for over ten days.

Somewhere over Kansas, aboard their private plane, the Starship, I decided to approach Page directly. “Why should I?” he shot back immediately. As the band’s founder and the guardian of their sound and image, mystique and respect weren’t just ideas to him—they were everything. “When I needed the magazine, they gave us a terrible review,” he said, repeating some of the harsh words from that piece. “Now they need me, and I don’t.””I don’t need them. Why should I? For Jann Wenner? Never.”

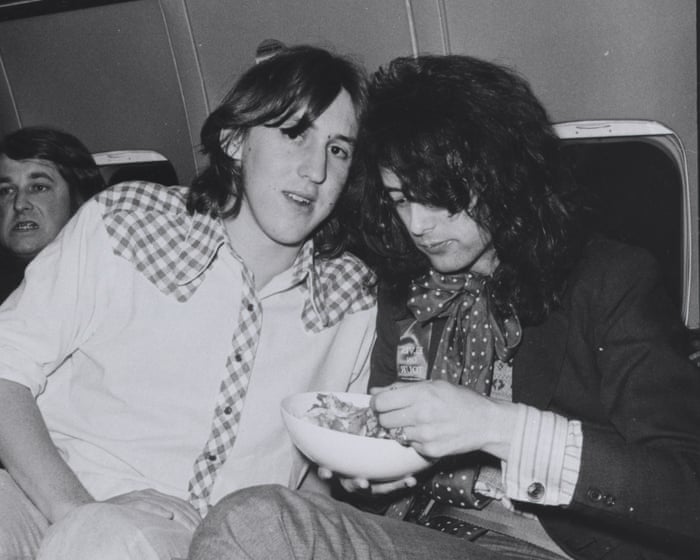

“I’m not Jann Wenner,” I continued. “I believe in the band. Let me tell the whole story for the fans.” The more I explained my plan, the more I seemed like a traitor to him. But he kept listening, so I kept talking. When he made himself some cereal, I followed him as he sat down and continued speaking.

“This is your chance to speak directly to the fans, and I promise the magazine won’t change a word.” I foolishly kept going. “As for the bad reviews, if I bought records based on what Rolling Stone praised, I’d have the worst collection of anyone I know.”

This made Page laugh—a sharp, appreciative chuckle.

“Well, if Joe Walsh trusts you,” he said, referring to the Eagles’ guitarist, singer, and songwriter, “then I should too.” I wasn’t sure I heard him right. “We’ll do the interview in New York,” he added. He turned away, and I caught a mischievous glint in his eye. I couldn’t tell if I’d achieved an almost unbelievable victory or was about to become the target of an elaborate joke.

The interview was scheduled for later that night. I rode the elevator up to Page’s room with my tape recorder in hand. He opened the door, dressed in his stage clothes: loose black satin trousers and a matching black cowboy shirt. He looked like a disheveled schoolboy as he led me into the sprawling three-room suite, which felt like it was designed for a Fellini film. In the middle of the main room stood a film projector. “Kenneth Anger is coming by to show me his film,” he said, “but let’s get started.”

Page opened up about his childhood—details he’d never shared before—and his feelings about Plant, the tour, the band, and himself. He suggested we first listen to one of my cassettes, a rare interview with Joni Mitchell, one of his favorite artists. The recording was a wonderful conversation between Mitchell and her friend, Toronto journalist Malka Marom.

We were interrupted by the arrival of Kenneth Anger, who brought the latest cut of Lucifer Rising. He had asked Page to provide the film’s score, and this would be the first time Page watched the movie with his music included. I sat next to Anger, the well-known occultist and author of Hollywood Babylon, as he projected the film onto the wall of Page’s hotel suite. I felt a world away from taking communion at Catholic school.

After Anger left, we returned to the Joni Mitchell tape. We listened until two in the morning and then began the interview. All of Page’s animosity toward the magazine and Wenner had vanished. He poured out more about his childhood, his thoughts on Plant, the tour, the band, and himself. He confessed that he never expected to live past 30, but here he was, two years beyond that, alive, reflective, and lonely in New York City. He mused about flying back to Los Angeles the next day for a night to see a girl he missed. He ended our conversation memorably and poetically, telling me, “I’m just looking for…”…an angel with a broken wing.” After our intense conversation ended, he asked if he could borrow the Joni Mitchell tape. I never got it back.

The article was quickly published, and that issue became one of Rolling Stone’s most successful ever. A few weeks later, a package arrived from Fong-Torres, filled with letters to the magazine from Led Zeppelin fans around the world. They were overflowing with fantasies, questions, stories, and gratitude for the interview. Rolling Stone had finally taken a chance on Led Zeppelin, even if belatedly, and the response was a whole lotta love.

“The Uncool” by Cameron Crowe is published by 4th Estate on October 28th. To support the Guardian, you can order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about Cameron Crowes legendary Led Zeppelin road trip framed in a natural conversational tone

General Beginner Questions

What is this Led Zeppelin road trip story all about

Its about a young journalist Cameron Crowe who while still a teenager went on tour with the rock band Led Zeppelin in 1975 to write a cover story for Rolling Stone magazine

Who is Cameron Crowe

Hes a famous filmmaker and writer known for movies like Almost Famous and Jerry Maguire Back in the 1970s he was a teenage rock journalist

How did this trip earn him class credit

Crowe was still in high school at the time He convinced his teachers to count the professional writing assignment for Rolling Stone as independent study credit allowing him to graduate early

What magazine did he write for

He wrote the cover story for Rolling Stone magazine

Deeper Dive Advanced Questions

Why was this interview considered a big break for him

Landing a cover story with the worlds biggest rock band while still a teenager gave him immense credibility and opened doors throughout his career in journalism and later in Hollywood

What was so special about his approach to the interview

Unlike many journalists Crowe immersed himself in the bands world by traveling with them This gave him unique behindthescenes access and resulted in a more personal and intimate story than a standard QA

Is this story connected to the movie Almost Famous

Yes absolutely Almost Famous is a semiautobiographical film written and directed by Crowe The main character William Miller is based on his own experiences as a young journalist on the road with a rock band

What were some of the challenges he faced on the trip

He had to navigate the chaotic rock n roll lifestyle gain the trust of a famously guarded band and maintain his professionalism as a journalist while being a fan himself

Did the band members like the final article

Reports suggest they were generally pleased Jimmy Page the bands guitarist reportedly felt it was one of the best pieces ever written about them because it captured the experience not just the sound