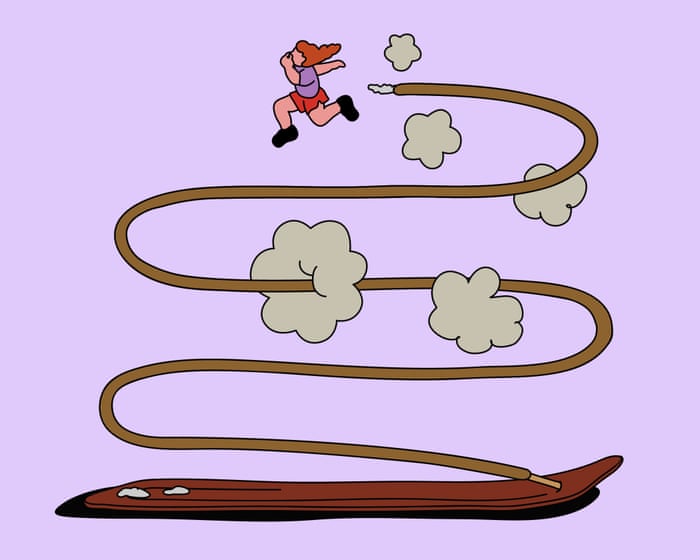

Several times a day, when the southbound Intercity train from Italy reaches Villa San Giovanni in Calabria, the trip comes to a striking pause. The train is detached from the tracks, gently loaded onto a ferry, and fastened down. Then, the whole vessel glides out into the Strait of Messina, heading for Sicily. This 25-minute crossing always turns into a spontaneous social gathering. Passengers leave their seats, heading to the ship’s top-deck snack bar to share freshly fried arancini, swap stories, and take in the view of Mount Etna’s distant summit before resuming their rail journey.

For travelers like me, the ferry ride is a delightful curiosity. But for locals, it has long been a core part of who they are. In his 1941 novel, Conversations in Sicily, Elio Vittorini writes about fruit pickers gathering on the ferry deck, enjoying big pieces of local cheese and the scenery. As the narrator joins them, he feels like a boy again, with the wind whipping across the sea, gazing at the ruins on both shores poetically separated by the water.

Soon, however, this nostalgic voyage may become a thing of the past. For months, Italian officials have been in final discussions to approve a new bridge linking Sicily to the mainland. In August, the government confirmed it would invest €13.5 billion and hire the Webuild Group to start construction. If built, it would be the world’s longest single-span bridge.

The Sicilians I know are doubtful. This isn’t the first time the Messina Bridge has been proposed only to be postponed. Although the idea dates back to Roman times, the modern story began in the late 1960s, when successive governments promoted the project as vital for reducing regional inequality. The original planners saw the bridge as a clear fix for the stark infrastructure gap between the industrial north and the agricultural south. By bridging that divide, they believed Sicily could finally draw the kind of international investment that other Italian regions had long benefited from.

But the bridge has never come to be. Over the years, obstacles like earthquake risks, environmental worries, and the constant threat of mafia corruption have repeatedly stalled the plans, making it seem unattainable. Even a few months ago, when the government announced its “final” approval, my Sicilian friends said they’d believe it when they saw it. They were right. Last month, Italy’s court of auditors halted the project over concerns about the legality of its funding, and as of now, it’s frozen once again.

Meanwhile, an old public debate is resurfacing, shedding light on contemporary Italian politics. On one side are bridge supporters, who view it as essential for the future, highlighting that it could create up to 120,000 local jobs annually and boost economic growth. On the other side are protesters from various political backgrounds, who accuse bridge advocates of being greedy opportunists focused only on profit. To them, the bridge represents the short-sighted exploitation of the island.

If you’ve visited Messina, you know these abstract ideological positions quickly clash with reality. While the city’s life and culture are as vibrant as anywhere on the island, Messina suffers from some of Italy’s worst social issues. The local government is notorious for financial mismanagement, with unexplained losses of public money and ongoing criminal and civil cases against several politicians, including two former mayors. Organized crime is widespread, and infrastructure fraud is already common among businesses with interests in the Strait. Poverty is a major concern, and the health service is in crisis.The school system is on its knees, teetering on the edge of collapse with some of the worst drop-out rates in the country. Against this backdrop, the claims of political supporters are hard to accept. Italy’s transport minister, Matteo Salvini, recently called the bridge “the most important public work in the world,” but his stance hasn’t always been so supportive. A decade ago, he argued the exact opposite. In a 2016 TV interview, now widely recirculated online in Italy, he dismissed the bridge as unfeasible from an engineering perspective and warned that frequent closures due to strong winds would render it ineffective. Given Sicily’s struggling public services, he contended that spending billions on such a project would be wasteful, and that the limited funds would be better used to strengthen local services.

Ironically, Salvini’s 2016 arguments have only grown more relevant as the climate crisis worsens. Over years of taking the ferry, I’ve seen firsthand how annual wildfires are intensifying. I’ve chatted with local farmers at the ferry’s top-deck bar, watching flames climb into the sky and light up scorched hillsides. I’ve heard stories from the deadly spring and summer of 2024, when Messina province endured its worst drought in decades. Crops failed, livestock perished. Reservoirs dried up, and aqueducts began to fail, leaving some areas without tap water for days at a time.

Webuild promotes the Messina Bridge as a historic opportunity, but residents don’t share that view—a recent survey shows 70% oppose the project. It’s easy to understand why: if you lived in a drought-stricken area, would diverting an estimated 15–20% of your local water supply to the project feel like an opportunity? If your home were near the coast, would you endure years of noise, environmental damage, and pollution for a massive public work that may not benefit you? And if you were one of the 4,000 people on either side of the Strait facing eviction and home demolition, would you be ready to pack your bags?

Salvini has pledged to address the court’s concerns and insists construction can begin by February 2026. I, for one, hope he reconsiders. At a time when the climate crisis is spawning new emergencies and deepening economic hardship, the bridge is simply not a priority. Sicilians urgently need political investment in public services and leaders who can rally collective action to ensure government funds are used wisely. Until then, Sicilians remain resilient, savoring one of the world’s most stunning ferry crossings—opting for community and arancini over an expensive steel cure-all.

Jamie Mackay is a writer and translator based in Florence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about Sicily that move beyond the endless debate about the proposed bridge to the Italian mainland

General Beginner Questions

1 Why does everyone keep talking about a bridge to Sicily

Its a decadesold idea to connect the island to mainland Italy promising economic growth and easier travel However it faces massive challenges like extreme cost engineering difficulties in a seismically active and deep strait and environmental concerns which is why many believe it will never be built

2 If we stop focusing on the bridge what should we be talking about instead

We should focus on real tangible improvements for Sicily such as modernizing its existing infrastructure boosting sustainable tourism supporting local agriculture and wine industries and preserving its incredible historical and cultural sites

3 What makes Sicily so special

Sicily is a unique crossroads of Mediterranean cultures with a rich history seen in Greek temples Norman palaces and Baroque towns It has active volcanoes stunning coastlines and is the home of iconic food like cannoli arancini and some of Italys best wines

4 Is Sicily a good place to visit for tourism

Absolutely It offers an incredibly diverse experience from the ancient ruins of the Valley of the Temples and the bustling markets of Palermo to the pristine beaches of San Vito Lo Capo and the dramatic slopes of Mount Etna

Advanced Practical Questions

5 What are the real infrastructure challenges Sicily faces today

The main issues are the poor maintenance of existing roads and railways which can make travel within the island slow and the need for more efficient and modern port facilities to better handle trade and tourism

6 How can tourism in Sicily be improved without a massive bridge

By investing in better local public transport promoting offthebeatenpath destinations to reduce overcrowding enhancing the quality of tourist services and developing more sustainable and ecofriendly travel options

7 What are some of Sicilys lesserknown economic strengths beyond tourism

Sicily is a major producer of highquality food and drink including renowned wines like Nero dAvola olive oil pistachios from Bronte and Mediterranean seafood There is also growing potential in film production and renewable energy particularly solar power

8 What is a practical example of a project that would benefit Sicily more than a bridge

A highp