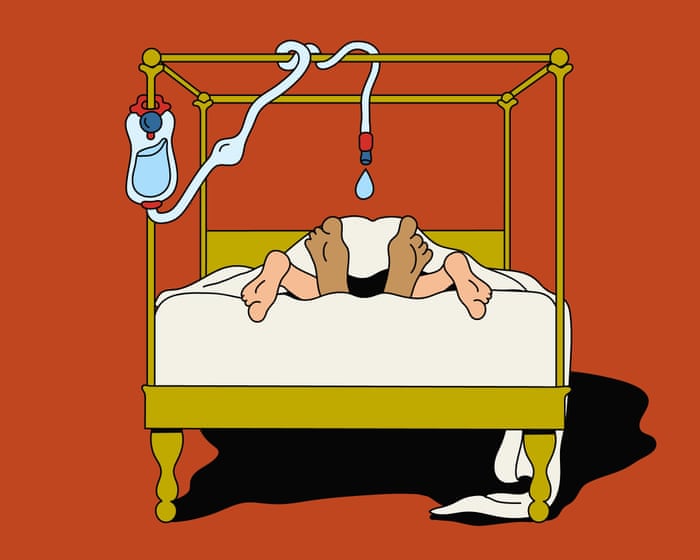

Paul Brown served as the Guardian’s environment correspondent from 1989 to 2005 and continued to write many columns afterward. Last week, he submitted his final column after being diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. From his hospital bed in Luton, Paul reflects on his 45 years of writing for the Guardian.

In the climate field, we all owe a significant debt to Margaret Thatcher. Her political views were opposed by me and many Guardian readers, but she took pride in being a scientist before a politician.

It was Thatcher’s curiosity that first led her to seek a scientific briefing on the dangers of the ozone layer hole and later on the even greater threat of climate change. At that time, she was at the peak of her international influence.

Meanwhile, the Guardian was growing increasingly interested in environmental issues. Organizations like Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace had evolved into large, radical campaigning groups, alongside more established ones like the WWF. Their young members increasingly relied on the Guardian to cover their activities and advertise green jobs.

As a general reporter for the paper, I was initially assigned to cover nuclear power when the science editor was ill. This allowed me to join various Greenpeace ships as a crew member. I participated in voyages to block the Sellafield pipeline that was discharging plutonium into the Irish Sea, and I traveled along the coast to highlight sewage dumping and unauthorized chemical waste pipelines.

I began reporting from international conferences aimed at protecting oceans and fish stocks. One of my most memorable experiences was spending three months in Antarctica on a Greenpeace vessel that successfully campaigned for the continent to be recognized as a world park. From Antarctica, I sent 26 articles via satellite, becoming the first journalist to file directly from the icy continent.

Upon my return, Thatcher was in New York warning the UN about the dangers of climate change. Soon after, I found myself in Geneva reporting as she and other European leaders cautioned that the world faced disaster without reducing fossil fuel use.

Back in London, Peter Preston, the Guardian’s editor-in-chief at the time, who once encouraged me by saying you can’t properly write about a place without visiting it, called me into his office and appointed me as environment correspondent. This came after the Green Party secured 16% in the European elections, which Thatcher viewed as a threat.

The agreements established at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro led me to travel the world, attending various COPs in capital cities.

I spent 16 years in that role, often working alongside John Vidal, who had a wide range of interests. He took on editing the weekly environment pages but would occasionally drop everything to pursue a unique idea that usually turned into a brilliant story. More than once, he left a note on my desk: “Could you handle the pages this week? Gone to Africa.”

From the start of my new job, it was clear that Thatcher’s grasp of science conflicted with her ideology. Restricting the free market wasn’t an option, so she did what many politicians do—diverted attention by creating something new, in this case, the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research to study the issue further. The center has since become world-renowned.

However, this pattern of politicians acknowledging the inconvenient truths of climate change but failing to take sufficient action has persisted. In fact, with the recent rise of blatant climate denial, the challenge has only grown.Climate change denial has become far worse since then. In the 1990s, I attended a whirlwind of international conferences. At the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, I witnessed George H.W. Bush and Fidel Castro pass each other in a hallway, both pretending not to see the other. If only I’d had a camera instead of just a notebook!

That summit led to the creation of the climate change convention, the biodiversity convention, and more, though it fell short on forest protection. The agreements made in Rio sent me traveling worldwide to cover subsequent Conference of the Parties (COPs) meetings, where progress on climate action moved at a snail’s pace.

Back in the UK during the 1990s recession, The Guardian’s news desk showed little interest in environmental issues after the Earth Summit ended, focusing instead on urgent matters like home repossessions and job losses.

As the decade continued, the Conservatives lost power in 1997. When John Prescott became environment secretary, environmental news gradually gained prominence. By the second Earth Summit in Johannesburg in 2002, it was back as a top priority.

By autumn 2005, I was overwhelmed with work. Following the devastating foot and mouth epidemic, every department—home, foreign, city, and features—wanted daily updates on my stories, each wanting theirs first. I learned from Vidal that missing from your desk was acceptable if you returned with a strong story. Meanwhile, The Guardian Foundation and various UN agencies began sending me to Eastern Europe and Asia to train journalists in environmental reporting. The workload became unsustainable, so I took voluntary redundancy in 2005. Six months later, The Guardian had five people doing my former role.

For the past 20 years, I’ve continued writing about climate change for numerous publications, including hundreds of Weatherwatch and Specieswatch columns for The Guardian. I’ve attended more COPs in cities like Paris and Warsaw and helped train young journalists to cover these complex events, giving back to the profession that has given me so much.

Yet, I’ve watched with ongoing dismay what I call the Thatcher syndrome: seemingly intelligent politicians repeatedly lacking the courage to implement necessary measures against the growing threat of climate change. At recent COPs like COP30 in Brazil, they’ve been surrounded by more fossil fuel lobbyists than environmentalists—a trend Vidal and I first noted in the 1990s. Must the well-funded fossil fuel lobby always prevail?

There’s also been another, in my view, very sinister development—A dangerous setback for climate action is emerging with the latest “nuclear renaissance.” I began reporting on the nuclear industry in the early 1980s and, like any well-trained journalist, was neutral at the time. Nuclear power appeared successful because it was part of the National Coal Board, and its true costs were hidden—not just from consumers but from the government as well.

The first nuclear renaissance occurred in the late 1980s during the construction of the Sizewell B nuclear power station. More plants were planned, but when Margaret Thatcher demanded to know the costs and resulting electricity prices for consumers, she discovered the government had been misled about the real expenses. Outraged, she canceled the rest of the program—one of my most memorable stories.

At least two more “renaissance” moments have come and gone, largely due to cost issues. Now, Keir Starmer’s government is enthusiastically pushing nuclear power, much to the dismay of environmental campaigners.

The government subsidies are enormous, effectively imposing a nuclear tax on struggling consumers. What is the government thinking? The fossil fuel industry, which supports nuclear power, is delighted. Decades of new construction without producing electricity mean at least another ten to twenty years of uninterrupted gas burning. It’s no coincidence that Centrica, primarily a gas company, invested in Sizewell C. With the project likely taking 10 to 15 years to complete, that’s a lot of extra gas burned and profits for shareholders.

The biggest puzzle is small modular reactors (SMRs). Theoretically built in factories and assembled on-site, they’re supposed to be easier and cheaper to construct. Originally defined as generating under 300MW—about a third the size of a traditional nuclear or gas plant—Rolls-Royce has redefined them as 470MW because even on paper, the economics didn’t work.

Several SMRs have been promised, but they don’t exist yet, except in designs or simulations. No factory has been built to produce their components, no prototype has been constructed, and no licensing process has taken place. The only thing known about them is that, on paper, they produce hotter waste at the end of their lifespan.

I know many of my Guardian colleagues may disagree, but as I step back after 40 years covering this industry, I urge them to keep a close watch. Over the years, I’ve been given wildly optimistic figures about construction costs, timelines, and electricity output. At worst, we’ve been consistently lied to. Unlike wind and solar, nuclear costs have risen for decades.

Now, it’s happening again at Sizewell C in Suffolk and in north Wales. The British public is forced to watch as the government wastes billions of our money. Journalists should expose this terrible misuse of resources. In the name of the climate, I ask them to examine the real facts, ignore the hype, and try to stop this waste before it escalates.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs based on the reflections of an environmental writer designed to be clear helpful and accessible

FAQs Insights from an Environmental Writer

Beginner Foundational Questions

1 Whats the single most important thing youve learned about the environment

That everything is connected A problem in the ocean affects the weather which affects our food supply You cant solve one issue in isolation

2 What is the biggest misconception people have about environmentalism

That its all about sacrifice and giving things up Ive found its more about innovation efficiency and building a healthier more resilient world which often leads to a better quality of life

3 Im just one person Do my actions really make a difference

Absolutely Individual actions create ripples They influence your social circle create market demand for sustainable products and build the collective momentum needed for larger change Your choices matter

4 Where is the best place for a beginner to start making a positive impact

Start with what you eat and what you throw away Reducing food waste and cutting down on singleuse plastics are two of the most effective and immediate steps anyone can take

5 Is it too late to fix the damage weve done

Its not too late to prevent the worst outcomes but the window for action is closing Every fraction of a degree of warming we prevent and every ecosystem we restore matters immensely for our future

Advanced Deeper Questions

6 What is an environmental issue that is more urgent than most people realize

The rapid loss of biodiversity We often focus on climate change but the collapse of insect populations pollinators and soil health is a silent crisis that threatens our entire food system

7 Youve written about systems change What does that mean in simple terms

It means we cant just recycle our way out of this We have to change the underlying rulesour energy systems transportation food production and economic modelsto make the sustainable choice the easy and default choice for everyone

8 What gives you hope after covering so many challenging stories

The incredible ingenuity of people Ive seen communities revive dead rivers engineers develop cheap solar power and farmers regenerate degraded land Human creativity when focused on solutions is a powerful force for good