The allegations against a religious leader were shocking: mistresses, illegitimate children, and embezzlement. Yet in 2015, Shi Yongxin, the head abbot of China’s Shaolin Temple—the birthplace of Zen Buddhism and kung fu—seemed untouchable. Known as the “CEO monk,” he had transformed the 1,500-year-old monastery into a commercial empire worth hundreds of millions of yuan. He held his ground and was eventually cleared of all charges.

But a decade later, the 60-year-old monk wasn’t so fortunate. In July, shortly after returning from a trip to the Vatican to meet the late Pope Francis, the Shaolin Temple announced that Shi was under investigation for allegedly misusing funds and fathering children with multiple mistresses. Within two weeks, he was dismissed and stripped of his monastic status. He hasn’t been heard from since. Shi’s downfall, over accusations similar to those he survived in 2015, was the most prominent in a series of recent scandals shaking China’s Buddhist temples.

These controversies highlight the increasingly fragile position of influential religious leaders in China. Official support for commercializing religious sites is giving way to a renewed emphasis on frugality and political loyalty.

In July, a well-known monk named Daolu (real name Wu Bing) had his title revoked by the Buddhist Association of China after Zhejiang police announced he was under investigation for fraud. Wu is accused of soliciting public donations under the pretense of helping unmarried pregnant women and needy children, only to spend the money on personal luxuries. Wu has not been heard from since the news broke, and it’s unclear whether he disputes the claims. The Guardian was unable to reach him for comment.

In August, a video of monks from Hangzhou’s Lingyin Temple counting stacks of cash at a table went viral, sparking a social media uproar. One user commented, “Those who worship Buddha become poor, and monks become rich.”

There is no inherent rule in Chinese Buddhism against accumulating wealth, according to Kin Cheung, an associate professor of East and South Asian religions at Moravian University. In medieval times, monasteries even functioned as banks, lending money to merchants at high interest rates. While raising funds for religious purposes is considered acceptable, personal enrichment can draw criticism.

This disapproval comes from ordinary people who view wealth as spiritually corrupting, and increasingly from the government. Under Xi Jinping’s leadership, there has been a crackdown on excessive wealth and corruption.

China’s temples have fluctuated in political favor throughout modern history. During the Communist Party’s land reform in the 1950s, monasteries lost their assets. Countless religious sites were damaged or destroyed in the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 70s. But with China’s economic reforms and opening up in the 1980s, temples regained popularity, often turning to tourism with explicit government support.

Among the prominent abbots who appeared to benefit personally during this period, Shi Yongxin was the most notable. Born Liu Yingcheng, he joined the Shaolin Temple in Henan at age 16 in 1981, when the site was in ruins. As he rose to head abbot, he negotiated with local officials to reopen prayer halls and sell tickets to tourists. Millions soon flocked to the temple, with the local government taking a 70% cut. Gift shops selling Shaolin-branded merchandise opened, and “Shaolin Inc.” was born.

Shi’s prominence grew along with the temple’s success. In 2006, the Dengfeng city government awarded him a luxury sports car worth 1 million yuan (£103,257) in recognition of his contributions.He made significant contributions to local tourism. When faced with criticism, he dismissed it by saying, “Monks also need to eat.”

With financial success came political influence. From 1998 to 2018, he served as a delegate to China’s National People’s Congress. Over the years, he met with notable figures like Nelson Mandela, Henry Kissinger, and Queen Elizabeth II. He even led a group of martial arts monks to Moscow for a special performance at Vladimir Putin’s invitation. This led one worker near the Shaolin monastery to comment that local Communist Party officials seemed to have far less political clout in comparison.

The Shaolin Temple’s popularity grew alongside China’s booming “temple economy,” which is expected to reach a market size of 100 billion yuan by the end of this year.

As China faces persistently slow economic growth, temples offer benefits to both local governments and ordinary people. Authorities gain from increased domestic spending as crowds visit these temple-tourist sites, while many individuals, struggling to find work or meaning in society, are turning to religion for spiritual guidance.

However, temples must carefully balance popularity with political compliance. “The Chinese government is very watchful of how much influence religion accumulates,” says Cheung.

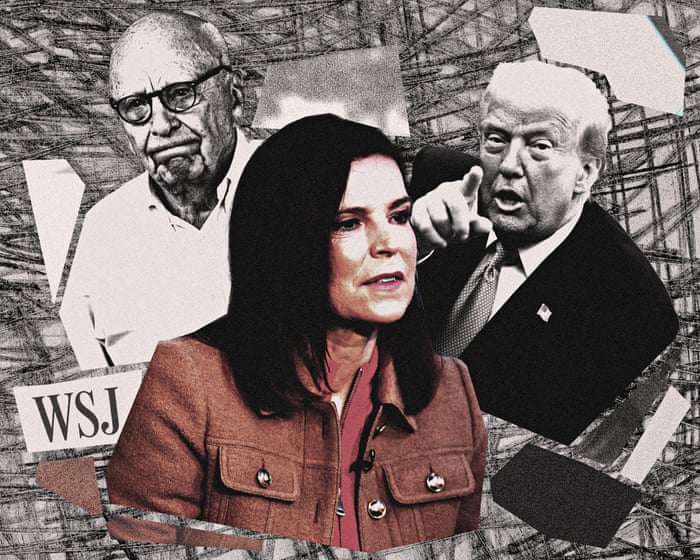

Experts believe Shi’s downfall may have been due to a loss of political backing rather than any specific misconduct. Ian Johnson, author of The Souls of China, notes, “It’s almost always about patronage—something else going on behind the scenes.”

Xi Jinping has shown a particular interest in traditional Chinese religions. Early in his career, he helped reopen important Buddhist temples and develop them into tourist attractions, setting an example for how the officially atheist Party could collaborate with religious institutions.

In recent years, however, Xi has sought to curb excessive religious commercialization. In 2017, Beijing updated its regulations on religious affairs, warning that Buddhist and Taoist sites risked tarnishing the “pure and solemn image” of China’s ancient religions. The new rules required these sites to operate as non-profits and banned the aggressive promotion of paid practices like incense burning and fortune-telling lot draws.

Now, it appears the Shaolin monastery, nestled in the rugged Song Mountains, is being reined in. In August, Shi Yongxin was replaced by an abbot named Shi Yinle, known for his frugality. The new abbot announced an overhaul of Shaolin’s commercial operations, halting paid performances, banning expensive rituals, and pledging to remove temple shops and unpopular fees.

“Shaolin should return to its true essence,” said Xie Chuanggao, a 57-year-old retired civil servant who visited the temple in August.

So far, however, the push against commercialization has been inconsistent. Daily martial arts performances by yellow-robed monks are free—but only for those who have paid the 80-yuan entrance fee to the temple complex. The site remains crowded with shops, and on a warm summer day, tourists flock by the busload to spend money on kung fu panda souvenirs and other trinkets.

Not everyone views Shi’s tenure negatively. Tom Li, a 21-year-old medical student at Henan University who visited Shaolin during his summer break, said, “Without him, the Shaolin Temple wouldn’t have achieved so much or gained international recognition. There are pros and cons, but you can’t deny his contributions.”

Li added that he wasn’t bothered by monks enjoying luxury goods: “After all, I’d want to drive a Range Rover too.”

The Shaolin Temple declined a request for an interview.

Additional research by Lillian Yang and Jason Tzu Kuan Lu.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about Chinas temple economy in a natural conversational tone with direct answers

BeginnerLevel Questions

1 What exactly is the temple economy

Its a term used to describe the commercial activities and revenue streams generated by religious sites primarily Buddhist and Taoist temples in China This includes income from entrance tickets donations selling incense and religious items and hosting tourist services

2 Why is the temple economy in the news lately

Its under scrutiny because of recent scandals involving highprofile monks and abbots These figures have been accused of misusing temple funds living lavish lifestyles and engaging in financial misconduct which goes against the principles of their faith

3 What are the benefits of the temple economy

A wellmanaged temple economy can provide funds for temple maintenance support for monks and nuns cultural preservation charitable works and boost local tourism and economic development for the surrounding community

4 Can you give me a famous example of a temple involved in this

The most famous example is the Shaolin Temple in Henan province Its known for its commercialization including its brand martial arts shows and a wide range of merchandise making it a major tourist destination and business empire

5 Is it wrong for temples to make money

Not inherently Temples need money to operate and preserve their heritage The controversy arises when the pursuit of profit overshadows religious duties when funds are mismanaged or when commercial practices exploit worshippers faith

AdvancedLevel Questions

6 How are temples typically funded in China

Funding is a mix of sources government subsidies for cultural heritage sites revenue from their own commercial activities private donations from worshippers and businesses and sometimes investments in unrelated commercial ventures

7 What are the most common problems or scandals

Common issues include

Embezzlement Abbots or managers siphoning temple donations for personal use

Lavish Lifestyles Highranking monks being exposed for owning luxury cars properties or having secret families

PaytoPray Exploitation Forcing visitors to buy overpriced incense or blessings to participate in rituals