What connects the word “vape,” the crying-laughing emoji, and the phrase “squeezed middle”? It’s not just a clever crossword clue for “millennial”—they’ve all been named word of the year. In fact, there are now so many “words of the year” that, if they were physical objects, they could fill a decent-sized museum. And that’s exactly how I like to think of them: as artifacts of their time, telling the story of a changing society.

This year’s winners—from “parasocial” (Cambridge Dictionary’s choice) to “rage bait” (Oxford English Dictionary), “67 (six-seven)” (Dictionary.com), and “slop” (Merriam-Webster)—will join the collection, though where they’ll be placed in the “museum” remains to be seen. Will they earn a spot in the permanent exhibit, alongside 2005’s “podcast” and 2015’s “binge-watch”? Or will they be relegated to the archives, where forgotten picks like 2007’s “w00t” gather dust next to David Cameron’s lesser-remembered, very bad idea—not Brexit (Collins, 2016), but “big society” (Oxford, 2010)?

Come play curator with me, and let’s take a tour.

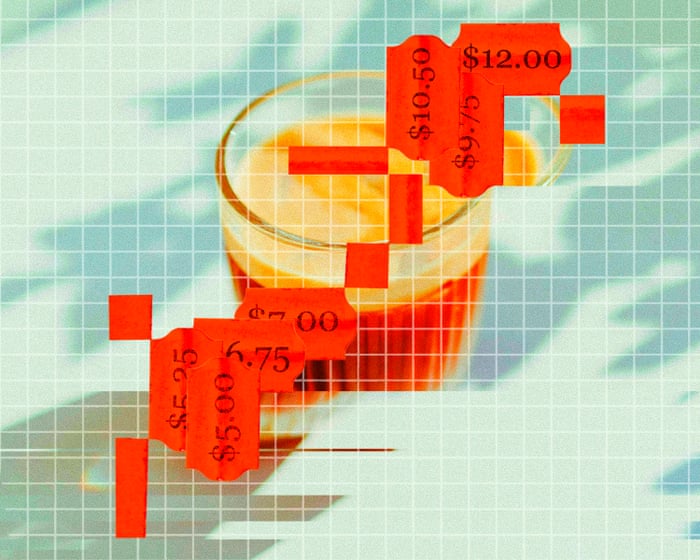

Looking back at the winning words from the past 20 years is like looking back at life through rose-tinted glasses. People often talk about the hope and optimism of the 2012 Olympics opening ceremony, but consider 2006 Britain, seemingly so untroubled that Oxford’s word of the year was “bovvered.” Or a time when, in contrast to 2024’s shared cultural experience of “enshittification,” the word was “sudoku” (Oxford, 2005). Were those times really much simpler—sorry, “simples” (a 2009 winner)? Probably not, especially since some words feel like prophecies. When I graduated into a recession in 2009, blissfully unaware of how it would define my generation, I should have paid more attention to 2008’s “credit crunch” and “bailout.” Still, earlier winners feel almost innocent: Merriam-Webster’s 2013 pick “science” (yes, just science in general) or Dictionary.com’s “change” (2010). Others, like “youthquake” (Oxford, 2017), “occupy” (American Dialect Society, 2011), and “feminism” (Merriam-Webster, 2017), speak to a hunger for progress, even as darker terms like “fake news” (Collins, 2017) and “post-truth” (Oxford, 2016) emerged.

But 2018 is where things get truly bleak. Words fit for an apocalyptic horseman dominate—”climate emergency,” “permacrisis,” “toxic,” “gaslighting,” “polarization”—before giving way to the language of fleeting tech crazes (“NFT,” “homer”) and variations on ennui (“quiet quitting,” “existential”). At least this will give future museum visitors an understanding of not only what burned Rome, but also the soundtrack playing on the metaphorical fiddle (Charli xcx, obviously—”brat” was Collins’ winner last year).

As for this year’s words, many fit right in. “Rage bait” surely belongs in the central gallery, as it’s now a permanent fixture of online life and a neat summary of how algorithms reward emotional manipulation. Meanwhile, I can only hope “slop”—the grim churn of mind-numbing AI video—goes the way of “metaverse” (Oxford runner-up, 2021) as another overhyped fad, quietly scrubbed from our lives once we all realize how rubbish it is. Off to the basement with you!

Then there’s “parasocial,” this year’s darkest winner. It may need a room of its own. It gained relevance amid stories of users bonding with AI and peak fan moments like Taylor Swift’s engagement dominating the internet. Personally, it’s not the “fan” element that gives me the chills, but…The real concern is how parasocial relationships are replacing genuine human connection, as we increasingly withdraw from shared lives into something far more isolated. This brings me to “six-seven.” Where does a “word” like that belong? Chosen as Dictionary.com’s 2025 Word of the Year, it’s the first ever to be used almost exclusively by teenagers. Meaning “so-so” but mostly deployed randomly to annoy adults, it’s a joke without a punchline. So there’s only one place for it: the Mona Lisa spot.

Hear me out. Recently, another trend has emerged in Words of the Year—one I can fully support: the fun words. Take “goblin mode,” a term for slobbing out (Oxford, 2022)—a truly poetic form of self-effacement. Or “rizz” (2023)? Some might argue it shouldn’t count since it’s just an abbreviation of “charisma,” but what feels more current than a word that works quickly and flexibly (“rizz” is also a verb, you know), and I’m sure remotely too, if it could.

Some may dismiss this slang as “brain rot” (Oxford, 2024). But humor is precious. It’s human, even when filtered through technology. And crucially, it’s full of potential. Because if you can share a joke, you can truly connect. And if you can connect, you can rebuild.

And so we return to “six-seven.” How about this for its exhibition label? “This form of ‘anti-humor,’ though it appears senseless and even nihilistic, is actually a piece of guerrilla performance art that exposes the meaninglessness of our times.” Okay, maybe I’ve taken this curator role a bit too far. Because it’s actually quite simple: saying “six-seven” randomly is just a very, very teenage thing to do. And that’s great.

I say this as someone who was in school during the peak of the Budweiser ad frenzy, when kids would burst out with “wassupppp” at literally any moment. Yes, it was random—that was the point, just as only the culprit and their friends were laughing. With “six-seven,” we see the same silly, slightly annoying, and quintessentially teenage energy. It may be internet slang, but its power lies in real life—forging social bonds among teens and creating a shared identity. Given everything we hear about teenagers being overly self-conscious, lacking friendships, and paralyzed by anxiety, this harmless bit of fun gives me hope. Maybe the kids really are alright.

Could it be the most hopeful word of 2025? The one that symbolizes the start of something beautiful again—a triumph of human nature as we begin to rebuild a new world? We’ll see. For now, let’s consider it on display, pending further review.

Coco Khan is a freelance writer and co-host of the politics podcast Pod Save the UK.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about the word of the year trend and the recent shift with sixseven

General Understanding

Q What is the Word of the Year

A Its a word or expression chosen by major dictionaries that is judged to best reflect the mood ethos or major concerns of the past year

Q What is the darker tone pattern people are talking about

A In recent years winners have often been serious negative or anxietyrelated Examples include vax goblin mode and rizz

Q What does sixseven mean

A Sixseven is a slang term from the Philippines It describes something that is irritating annoying or offlike a minor but persistent inconvenience or a person who is being difficult

About the Shift in Pattern

Q How does sixseven break the darker pattern

A While it describes an annoyance its fundamentally about minor everyday frustrations rather than largescale societal crises existential dread or global anxiety Its more relatable and mundane

Q Is sixseven actually a positive word

A Not exactly positive but its significance is neutralizing It shows that the cultural conversation can be captured by a word about shared petty annoyances rather than overwhelming negative forces Its a shift from catastrophic to casually irritating

Q Who chose sixseven as the Word of the Year

A This is a key point Sixseven was not chosen by a major global dictionary like Oxford It was named the Word of the Year for 2023 by the Sawikaan conference in the Philippines which focuses on Filipino language and culture Its viral spread online is what brought it into the global conversation about the word of the year trend

Deeper Analysis Impact

Q Why does the choice of Word of the Year matter

A It acts as a cultural time capsule Analyzing the choices over time can show us what societies are