If you think true crime is unavoidable when scrolling through Netflix or chatting with coworkers, try working in the documentary industry. As you move from one pitch meeting to another, presenting your passion project about the history of mime or the secret lives of snails, you can almost predict the question before it’s asked: “Got any other ideas?” Preferably something involving murder.

I started making documentaries in 2015, just as HBO’s The Jinx and Netflix’s Making a Murderer brought true crime back into the spotlight. These shows, framed as both murder mysteries and social justice efforts, seemed to signal a fresh start for the genre. But soon, they were followed by a flood of similar content, often following repeatable formats like Netflix’s Conversations With a Killer series, each season built around rediscovered interviews with notorious serial killers.

Still, I wasn’t completely against the trend. As a longtime fan of true-crime films and shows, I was drawn to the puzzle-solving aspect—how clues come together over time, making a tidy resolution feel just within reach, even when we know the case remains unsolved.

I still remember watching the French true-crime series The Staircase for the first time when it aired on the BBC in 2005. (Later, during the true-crime boom, Netflix picked it up and expanded it, and HBO adapted it into a dramatic miniseries.) As each new revelation seemed to point to novelist Michael Peterson’s innocence in the death of his wife Kathleen, I became convinced he’d be acquitted in the end—even though I’d already looked him up online and found he was in prison in North Carolina. That’s the power of the puzzle.

Of course, I had doubts about building entertainment from real people’s lives and tragic deaths. But I told myself that creating something engaging could be a way to reach a large audience with meaningful content. Maybe true crime’s familiar patterns and formulas could serve a higher purpose. These ideas swirled in my head as I began to imagine making my own true-crime documentary.

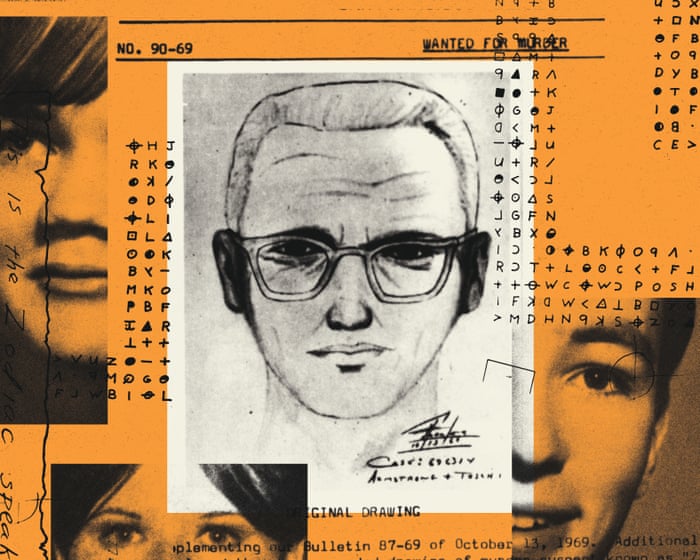

I came across a memoir called The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up by Lyndon Lafferty, a recently deceased California highway patrol officer. In it, Lafferty describes his decades-long pursuit of the infamous Bay Area serial killer after a chance encounter with his suspect at a rest stop.

The standard response to any ethical concerns is simple: it’s all for the sake of the victims.

This wasn’t the first book I’d read about the Zodiac Killer, who murdered at least five people in the late 1960s and secured his place in crime history by sending cryptic letters and codes. That was Robert Graysmith’s 1986 bestseller Zodiac, which I discovered through David Fincher’s acclaimed 2007 film adaptation. But Lafferty’s account was by far the most unique, filled with bizarre twists and dramatic cliffhangers, alongside classic true-crime elements: a determined investigator, clues uncovered over decades, and a killer still on the loose.

As I sought the rights to adapt The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up for the screen, the film started taking shape in my mind. I envisioned a mysterious cold open, reenacting Lafferty’s pivotal rest stop encounter with tense close-ups. From there, the title sequence would…The film hums to life, opening with a collage of sepia images that hint at the dark story ahead. I pictured the worn-out diner where I would meet with retired police officers, seasoned journalists, and others who had stuck around for fifty years.

I was set on avoiding the confirmation bias that taints many theories about the case, aiming to present evidence both for and against Lafferty’s suspect. But after five decades of digging by professionals and amateurs alike, the sheer volume of evidence was overwhelming—far too much for a single film. It quickly became unclear how I was deciding what to include. For instance, there are at least six different descriptions of the killer’s height, and the one matching Lafferty’s suspect was no more reliable than the others. This mountain of paperwork makes almost any crime ripe for the true-crime treatment.

Are we all just driven by an endless, voyeuristic hunger for the gruesome?

As long as laws have existed, people have told stories about breaking them, and cinema has been filled with dark tales from its earliest days. Motion picture pioneer Siegmund Lubin dramatized the shocking 1906 murder of architect Stanford White in his film The Unwritten Law, releasing it within a year of the crime.

However, the modern true-crime film has a shorter history, drawing most of its style and storytelling from Errol Morris’s 1988 documentary classic, The Thin Blue Line. That film, which revisited the shooting of a Dallas police officer a decade earlier, established the template for hazy reenactments and speculative timelines now common in everything from low-budget TV shows to award-winning dramas (and helped blur the lines between them). It also achieved what all true crime strives for: influencing the outcome of the case it covered.

What’s rarely copied is its commitment to ethical standards. Even the few true-crime works that have similarly impacted legal proceedings have operated with much looser morals: The Jinx secured a confession from suspected serial killer Robert Durst but edited his words in post-production, worried they weren’t incriminating enough.

The standard defense against ethical criticisms of true crime is simple: it’s all for the victims, and occasional moral lapses are a small price to pay for giving closure to them and their families. The unsettling tone of much modern true crime comes from the clash between this self-righteous claim and the sensational choices it justifies.

In the CBS miniseries The Case of: JonBenét Ramsey, criminal behavioral analyst Laura Richards, who calls herself a victim advocate, suggests that six-year-old JonBenét may have been killed by her preteen brother—a theory he has always denied and for which he was never charged. To test this idea, she has a child actor hit a skull wrapped in pig skin and a blond wig with a flashlight. As the resulting crack is compared to an autopsy photo, Richards insists, “This is quite hard to do, but we need to do this, to see what it looks like.”

It’s unclear whether those for whom this is supposedly done appreciate it. Netflix’s 2022 series Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story defended its graphic reenactments by claiming sympathy for the victims’ families, yet the producers didn’t reach out to any of them. Several relatives later criticized the show, including Eric Perry, a relative of Dahmer victim Errol Lindsey, who spoke out against it.The Los Angeles Times once noted, “We’re all just one traumatic event away from the worst day of our lives becoming our neighbor’s favorite binge-watch.” Following this, two more Monster series were produced, focusing on the Menendez brothers and Ed Gein.

True crime often appeals to a higher authority: history itself. It’s said that dark clouds linger over communities where horrific crimes occurred, and we have a duty to face these collective traumas, no matter how painful. As I arrived in Vallejo, California—the heart of the Zodiac Killer’s spree—in August 2022 to scout locations, I could already imagine future interviewees solemnly describing the town’s sinister atmosphere.

But reality was far more ordinary. Daily life in Vallejo seemed largely unaffected by events from half a century ago, and many residents weren’t even aware of the city’s grim notoriety. During a cab ride from the airport, the driver was more eager to talk about local rappers like Mac Dre, E-40, and Nef the Pharaoh than infamous killers. Looking out the window, I pictured the moody filters I’d need to portray the town as permanently scarred by its past.

Soon, that became irrelevant. Two days later, while having lunch at a diner I considered for filming, I received an email saying negotiations for the rights to Lafferty’s book had collapsed. No reason was given, but I suspected someone with more money or a stronger resume had recognized the book’s cinematic appeal and outbid me.

Stepping outside, I paused to assess my situation. Without Lafferty’s fifty-year quest for justice adding drama, the Zodiac Killer case was just a collection of facts accessible online. Without his suspect casting a shadow over the town, Vallejo was merely a quiet city with a Six Flags park. I glanced around; the sun was shining, and there wasn’t a dark cloud in sight.

This wasn’t my first failed project, and I expected to recover quickly and move on. Back in London, though, Lafferty’s story stuck with me. I found myself detailing shots, scenes, and the entire plot of the unmade film to anyone who’d listen. The eerie familiarity of true crime had made the project easy to envision and now impossible to forget. That frustration eventually felt like a subject worth exploring itself.

In my final film, bluntly titled Zodiac Killer Project, I narrate the failed film step by step over footage of the ordinary Vallejo scenes I encountered upon arrival. I briefly indulge in true crime’s visual tropes—shell casings clattering, crime-scene tape stretching out—but keep it fleeting.The film’s power lies in its distance—it’s shaped more by what’s left unseen. As I piece together each scene and explain the project’s intentions, I keep confronting the unresolved ethical dilemmas and narrative shortcuts that define both this film and the true crime genre as a whole.

This work serves as both a tribute to the true-crime documentary I never made and an effort to wrestle with true crime itself, as it continues its relentless spread through the documentary world. If these aims seem at odds, they mirror the conflicted feelings I’ve seen in many colleagues who’ve tried to create thoughtful, ethical true-crime films while openly questioning whether the genre is beyond saving.

This ambivalence might explain why true crime has become so eager to turn the spotlight on its own audience. From the unsettling high-budget drama “Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story” to the provocative docuseries “Don’t Fk With Cats,” they all include moments that challenge why we’re drawn to these stories. Are viewers confronting their deepest fears as a form of exposure therapy, they ask with grave concern, or are we reveling in others’ suffering to feel better about ourselves? Or are we all just helplessly drawn to the morbid and macabre?

Whatever the answer, the documentary industry seems to absolve itself. The endless stream of true-crime films, TV shows, books, and podcasts released weekly is framed as simply meeting audience demand. Or so we tell ourselves. But every time I’m drawn back into true crime’s murky depths—after having very publicly sworn it off—it hints at another reality: that the masses of true-crime enthusiasts might just be struggling to keep up with what we keep producing.

Zodiac Killer Project opens in theaters on November 28. Screening information is available at zodiackillerproject.com.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs based on your experience with the Zodiac Killer film project and the true crime world

General Beginner Questions

Q What is this about

A Its about a filmmakers personal journey after a failed attempt to make a movie about the Zodiac Killer which led them to explore the often dark and complex world of true crime

Q Who is the Zodiac Killer

A He was an unidentified serial killer who operated in Northern California in the late 1960s and early 1970s He is known for sending taunting letters and ciphers to the press

Q Why did you want to make a film about the Zodiac Killer

A Like many I was drawn to the mystery Its an unsolved case with cryptic codes and a hidden identity which is a compelling starting point for a story

Q What does the unsettling core of the true crime world mean

A It refers to moving past the surfacelevel mystery and confronting the grim reality of the crimes the impact on victims families and the sometimes obsessive and ethically complicated nature of the community that forms around these cases

Deeper Dive Process Questions

Q Why was your effort to make the film unsuccessful

A The project faced several common hurdles like difficulty securing funding for a dark subject and the challenge of finding a new respectful angle on a story that has been covered many times before

Q What was the most surprising thing you learned while researching

A I was surprised by the sheer volume of misinformation and unverified theories online Its incredibly difficult to separate fact from speculation even in a welldocumented case

Q Did researching this case affect you personally

A Yes Immersing yourself in the details of reallife violence and tragedy for an extended period can be emotionally draining and change your perspective on humanity

Q Whats the biggest ethical challenge in creating true crime content

A Balancing the publics fascination with the story against the respect and sensitivity owed to the victims and their living families Its easy to forget that these were real people not just characters

Practical Community Questions

Q Whats a common mistake people make when first getting into true crime

A They often get caught up in the mystery