The UK has joined several of Europe’s more hardline governments in calling for human rights laws to be “constrained” to allow Rwanda-style migration agreements with third countries and to enable the deportation of more foreign criminals.

Twenty-seven of the 46 Council of Europe members, including the UK, Hungary, and Italy, have signed an unofficial statement. This statement also urges a new framework for the European Convention on Human Rights, which would narrow the definition of “inhuman and degrading treatment.”

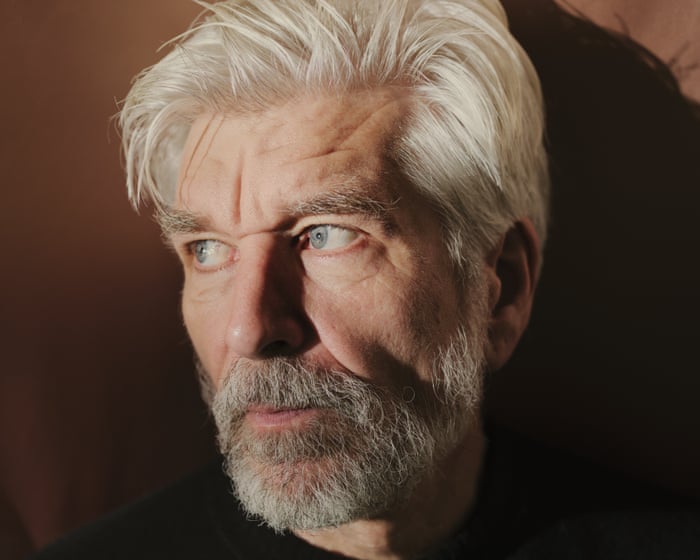

The statement follows a meeting of the council in Strasbourg on Wednesday, part of a broader push to change how human rights laws apply in migration cases. The UK’s Deputy Prime Minister, David Lammy, attended the meeting and was expected to argue that the rules must not prevent countries from tackling illegal migration.

Countries such as France, Spain, and Germany have declined to sign this statement. Instead, they have endorsed a separate, official declaration supported by all 46 governments.

These two separate statements highlight deep divisions across Europe over how to address irregular migration and whether to continue guaranteeing rights for refugees and economic migrants.

The letter signed by the 27 countries argues that Article 3 of the convention, which bans “inhuman or degrading treatment,” should be “constrained to the most serious issues” so it does not prevent states from making proportionate decisions on expelling foreign criminals, including in cases involving healthcare and prison conditions.

It also contends that Article 8 should be “adjusted” regarding criminals, giving more weight to the nature and seriousness of the offense and less to the criminal’s ties to the host country.

Hinting at European deals with third countries willing to house rejected asylum seekers, the statement says: “A state party should not be prevented from entering into cooperation with third countries regarding asylum and return procedures, once the human rights of irregular migrants are preserved.”

The other signatories are: Denmark, Albania, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Montenegro, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia, Sweden, and Ukraine.

The separate, formal declaration signed by all member states does not identify problems with specific articles of the convention.

The head of the body overseeing the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) said ministers had taken an “important first step forward together” by agreeing to a political declaration on migration and the ECHR and supporting a new recommendation to deter migrant smuggling “with full respect for human rights.”

Council of Europe Secretary General Alain Berset told reporters: “All 46 member states have reaffirmed their deep and abiding commitment to both the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Court of Human Rights. This is not rhetoric. This is a political decision of the highest order. But ministers have also expressed their concerns regarding the unprecedented challenges posed by migration and the serious questions governments face in maintaining societies that deliver for citizens.”

Labour’s poll ratings have dropped significantly since the general election, with the rise of Nigel Farage’s Reform UK partly driven by concerns about immigration—both legal and via small boat crossings of the Channel.

Unlike the Conservatives and Reform UK, Labour is committed to remaining within the ECHR, which was established after the Second World War.

In a Guardian column, the British Prime Minister and his Danish counterpart, Mette Frederiksen, acknowledged that the “current asylum framework was created for another era,” adding: “In a world with mass mobility, yesterday’s answers do not work. We will always…”We must always protect those fleeing war and terror—but the world has changed, and our asylum systems must change with it.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about the UKs push to limit European human rights laws designed to be clear and conversational

Beginner Definition Questions

1 What are the European human rights laws people are talking about

This primarily refers to the European Convention on Human Rights a treaty created after WWII to protect fundamental rights across Europe It is enforced by the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg France Its separate from the European Union

2 Why is the UK trying to change this

The UK government argues that the Strasbourg court has overreached making decisions that interfere with UK sovereignty and democratic decisions made by Parliament They believe UK courts should have the final say on human rights matters in the UK

3 What is the Bill of Rights they keep mentioning

This is a proposed UK law intended to replace the current Human Rights Act 1998 The Bill of Rights would make UK courts the ultimate authority on human rights cases and aim to limit the influence of the European Court of Human Rights in UK law

4 Is this because of Brexit

Its related but separate Brexit was about leaving the European Union The ECHR is part of the Council of Europe which includes 46 countries like Ukraine and Turkey However a desire for greater legal independence is a common theme in both

Advanced Impact Questions

5 What specific issues does the UK government have with the current system

Key complaints include

Deportation of foreign criminals Blocking removals to countries where there is a risk of illtreatment even if the individual is considered dangerous

Rules on voting rights for prisoners

Operational decisions For example the ECtHRs 2022 intervention that temporarily halted the UKs Rwanda asylum flight

6 What are the main benefits the government claims this push will bring

They argue it will

Restore Parliamentary Sovereignty

Curb abuses of human rights claims like those by convicted criminals

Make the UK Supreme Court the final arbiter of human rights

Provide a clearer UKcentric framework for rights