The day after the Brexit vote in 2016, the pub in my hometown opened early. People celebrated under Union Jacks, raising pints in triumph. Meanwhile, I was in a London rehearsal room, surrounded by people who were stunned and angry. On my tube ride home, the media echoed what I’d heard all day: Leave voters were ignorant and racist. My town had voted over 70% to leave. Three years later, the constituency elected a Conservative MP for the first time in its history. More recently, it voted for Reform in a council election. There comes a point when the unthinkable becomes inevitable.

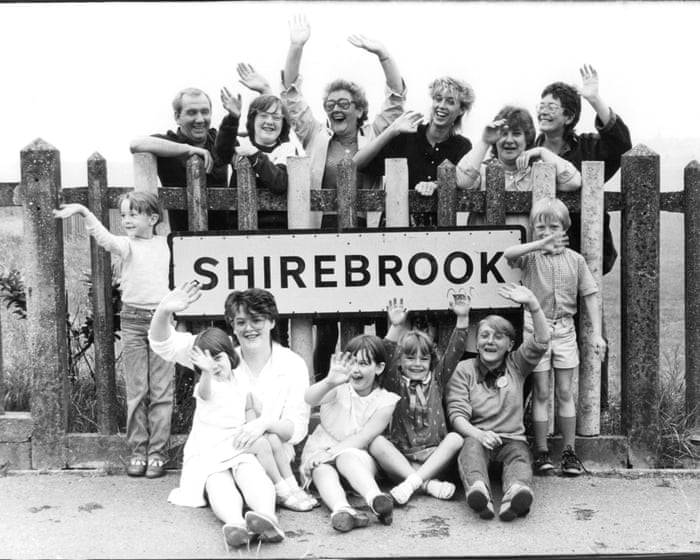

My town is in the East Midlands. Once, coal mining and manufacturing provided jobs for many; now, a massive Sports Direct warehouse dominates the local economy. Many Eastern Europeans have settled in Shirebrook and work there. Lately, with all the anger and xenophobia directed at asylum seekers and migrants, I’ve been reflecting on towns like mine—and there are many.

One thing I value most about writing plays is the chance to suspend judgment. My characters speak, and I listen; they act, and I observe. It’s liberating, and I’m often surprised by how much they reveal: characters are as complex as we allow them to be, and real people are no different. Yet we often try to shrink others, to simplify them—I catch myself doing it in daily life too. It lets us tell that joke or “win” that argument.

In my play, Till the Stars Come Down, I’m not trying to win an argument, and the humor never comes at the characters’ expense. The story unfolds on the day of a wedding between a local woman and a Polish immigrant. It’s about a multigenerational working-class family navigating a changing community and world, along with their own deepening desires and losses. The play is passionate, funny, and deeply political, but you won’t hear characters debating Brexit or Reform. They live politics; they don’t comment on them.

I take inspiration from Chekhov, whose plays aren’t usually seen as overtly political. He doesn’t state his own views, and his characters rarely do. Yet his works portray families living through major cultural and economic shifts in societies on the verge of revolution. When Chekhov was writing, the 1905 Russian Revolution was still ahead, but if you listen closely, you can hear the bomb ticking under the floorboards of those family homes.

I believe there’s a similar ticking now—not under dusty floorboards, but in the hearts of the people I write about. They want more, and they often demand it. They’re raw and combustible. In the play, there are moments when they sense their own significance in the universe, when life feels grand and mysterious, and other times when they feel small and frustrated, lashing out as a result.

It’s rare to see that full range of experience reflected in our culture. When white working-class lives from the Midlands or northern England are portrayed, it’s often set in the past, as if there’s uncertainty about who these people are today—better to go back to when we thought we knew. But we have to understand them now, because they aren’t just part of the past; they may well shape the future.

I’m sometimes skeptical about claims that art can change society. But I do believe theatre can be a place where we sit and listen to people we might not otherwise meet, sharing in their lives as they unfold before us. We can’t change the channel, block them online, or cross the street. We might still reduce them with our prejudices, denying their complexity, but many of us won’t. Instead, we’ll sit in the dark, laughing and crying, falling in love one moment and growing frustrated the next. A lot lies in that shared experience.I never imagined this play would be performed around the world, from Tokyo to Athens to Montreal. That lack of vision came from not believing that a story about a specific working-class family in a particular Midlands town could feel universal. How could I not have realized that we are all deeply different, yet exactly the same? The human family we belong to transcends cultures and classes when it reveals our emotional lives: what it means to feel joy, shame, love, grief, desire, to fear the future rushing toward us—and not be ready for it.

The future is always closer than we think. It’s built from the present; it is, in fact, today. In Greek tragedy, people often understand their situation too late. In my play, set during another intense summer, characters often mention the heat, the fire, as if they already sense their world is about to go up in flames—and yet they don’t change direction. We, too, have been trying to put out fires, both local and global, while carrying on much as before. By now, I think it’s clear where that leads.

If the end is the beginning, I’ll leave you with the first line of my play: “I can smell burning.”

Beth Steel is a playwright. Till the Stars Come Down is at the Theatre Royal Haymarket in London until 27 September.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about the topic inspired by Beth Steels quote I come from a workingclass town in England When will society stop viewing us as a thing of the past

General Beginner Questions

Q What does workingclass actually mean

A It traditionally refers to people employed in manual or industrial jobs often with lower incomes and less formal education than the middle or upper classes

Q Why does Beth Steel feel her town is seen as a thing of the past

A Because many traditional industries that supported these towns have closed down Society often associates them with a bygone industrial era rather than seeing their presentday communities and challenges

Q Is this just a problem in England

A No this is a common experience in many postindustrial regions across the world like the Rust Belt in the United States or former mining areas in Wales and Northern England

Deeper Advanced Questions

Q What are the stereotypes about workingclass people that contribute to this feeling of being outdated

A Common stereotypes include being uneducated resistant to change politically simplistic or solely defined by their historical industry These overlook the diversity resilience and modern realities of these communities

Q How does this viewing as the past actually affect peoples lives

A It can lead to economic neglect political marginalization and a negative cultural perception that impacts pride and selfworth

Q Beyond nostalgia what is the value of these communities today

A They hold immense value in their strong sense of community shared history resilience and practical skills They are not relics but living places facing modern issues like any other

Q What role does the media play in this perception

A Media often portrays workingclass towns either through a lens of poverty and social issues or romanticized nostalgia for a lost industrial age Both fail to show the full contemporary picture

Practical ActionOriented Questions

Q What can be done to change this perception