Many people, including my monolingual father, advised me against studying languages. I remember him saying, “You’ll never be as fluent as a native speaker. Why bother?” when I was choosing my university degree.

More than ten years later, I’ve gathered a wealth of experiences. I’ve worked the front desk at Sotheby’s in Madrid, taught theatre and English to Syrian children excluded from mainstream schools in Beirut, spoken about sustainable development goals for Arab audiences at the UN, and trained journalists in one of Ecuador’s most dangerous cities. I’ve dated who I wanted, turned down who I didn’t, sung songs, and cooked recipes—all in languages that aren’t my own. Most importantly, I changed my dad’s mind.

Nick Gibb, the former schools minister, was right when he recently told The Times that the UK’s decline in language learning harms our global reputation. Our international peers are far more multilingual; in Europe, we’re among the least likely to speak a second language. Brits weren’t always poor language learners—in 1997, 82% of boys and 73% of girls took a modern language at GCSE. By 2018, that had dropped to 50% of girls and just 38% of boys.

For much of the 20th century, language learning became more accessible, moving beyond the elite circles of Eton or Jane Austen’s accomplished heroines. But this progress was undermined by the difficulty of language GCSEs, which are still graded more harshly than other subjects.

Instead of making exams fairer, challenging the idea that languages are too hard, or improving teaching quality, the 2004 Labour government removed the requirement to take a language GCSE altogether. The impact has been disastrous.

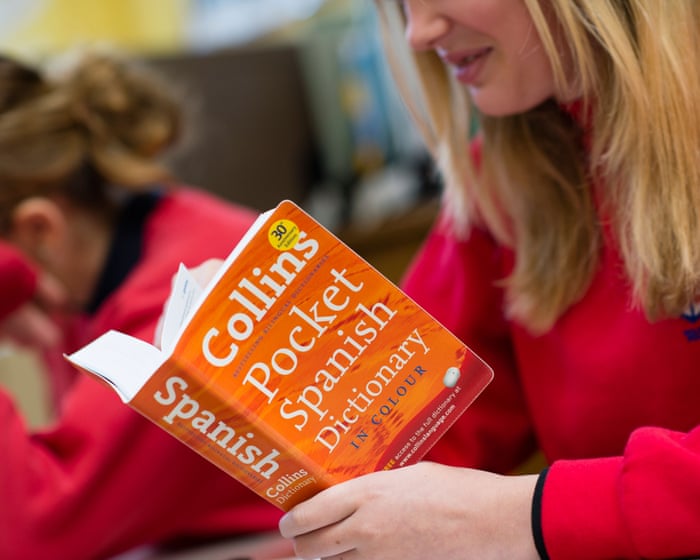

Some languages are faring better than others: Spanish is growing in popularity, French is stabilizing after a sharp decline, but German—despite being the most requested language in UK job ads—is falling fast at GCSE. Worse, language learning is once again becoming an elite pursuit. In poorer areas, only 46–47% of Year 11 pupils study a language at GCSE, compared to 66–67% in wealthier areas—a 20-point gap.

This decline at GCSE level has led to fewer students taking languages at A-level and university. Even as more people attend university, applications for language degrees have dropped by over a fifth in the last six years. Many universities, especially those founded after 1992, have closed their modern languages departments. Brexit and the pandemic have only made things worse by limiting study abroad opportunities.

I was lucky to attend a school that valued languages, and even luckier to grow up around multilingualism—something research shows motivates students in England to learn languages, even in monolingual areas. While my dad saw little value, my mum—fluent in Italian and the minority dialect my grandmother brought from the Ligurian Apennines in the 1950s—encouraged me to learn as many languages as possible.

Without the Spanish I started at 13, the Arabic I took up at 18, and the Italian that’s been part of my life since birth, I wouldn’t be the journalist or the person I am today. It’s not just about the conversations I’ve had or the sources I’ve read—it’s about the life-shaping experiences that come with learning languages. That’s why languageEmployers value language skills not just for the words and grammar, but for the soft skills that come with learning them—resilience, creative thinking, and openness to new ideas, all of which are nurtured by immersing oneself in different cultures.

Multilingual individuals have access to a wider range of job opportunities that require these skills, along with cognitive benefits like enhanced creativity and even a potential delay in the onset of Alzheimer’s. Many Britons who assume English alone is enough while traveling quickly learn otherwise when faced with vulnerable situations abroad or when unable to help others at home. Earlier this summer, for example, an elderly Portuguese woman on the Tube stopped me because she was lost on her way to a hospital appointment. I only know a few dramatic fado lyrics and how to say “I don’t speak Portuguese,” but my fluent Spanish allowed us to understand each other, and I could guide her to the right stop.

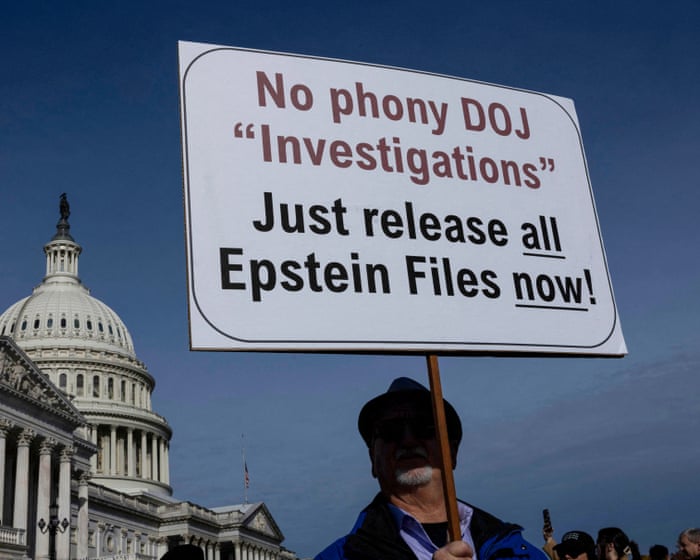

Despite efforts in the 2010s to boost language learning through the English baccalaureate, the situation in the UK has deteriorated so much that even the quirky language app Duolingo is stepping in, recently sponsoring a Westminster challenge encouraging politicians to outdo each other in language learning.

So how do we fix this? A recent think tank report recommended immediately hiring more international language teachers to fill gaps and ensuring language learning remains a statutory right for students up to age 18.

I have additional ideas, starting with better appreciating the rich diversity of languages that immigrants bring to the UK. We often wrongly assume that assimilation in Western countries means adopting English monolingualism, rather than fostering sophisticated bilingualism across generations. Expanding heritage language opportunities, through collaboration between the UK government and international partners, would strengthen global ties as well as individuals’ connections to their families and communities.

We should also acknowledge our own indigenous languages. When Keir Starmer tweeted this year, “If you want to live in the UK, you should speak English,” he overlooked the language policies of our devolved nations, which accommodate Welsh, Gaelic, and Scots.

Considering both the contributions of immigrants and our ancient Celtic languages, it becomes clear that the UK is far from monolingual. Embracing multilingualism as a British trait might surprise or even annoy some, but—as I’d be happy to explain in the four languages I speak—that’s exactly why we should do it.

Sophia Smith Galer is a journalist and content creator. Her second book, How To Kill a Language, will be published next year.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs based on the article Time for a reality check Britain cant be a major global player unless we become more multilingual by Sophia Smith Galer

General Beginner Questions

1 Whats the main point of this article

The main point is that for the UK to remain influential and competitive on the world stage after Brexit its citizens and government need to prioritize and get much better at learning foreign languages

2 Why is being multilingual so important for a country

Speaking other languages builds stronger trade relationships improves diplomacy allows for better cultural understanding and gives a country a competitive edge in the global economy

3 Isnt English the global language Why do we need to learn others

While English is widely spoken relying solely on it is seen as arrogant and puts the UK at a disadvantage It creates a barrier to deeper business deals and political alliances as negotiating in someone elses language shows respect and builds trust

4 What languages should people in Britain learn

The article suggests looking beyond just French German and Spanish Languages like Mandarin Chinese Arabic Russian and Portuguese are crucial for future global trade and politics

Deeper Advanced Questions

5 How does being monolingual hurt Britains soft power

Soft power is influence through culture and attraction rather than force Not speaking other languages limits the UKs ability to effectively share its culture values and ideas reducing its global appeal and influence

6 Whats the link between Brexit and this language argument

Leaving the EU means the UK must build new trade and diplomatic relationships independently Not speaking our partners languages puts us in a weaker negotiating position and makes it harder to secure favorable deals

7 What are the common problems or barriers to becoming more multilingual in the UK

Key problems include a lack of government funding and priority for language education in schools a cultural mindset that everyone speaks English and a shortage of qualified language teachers

8 Does this just apply to politicians and business leaders or to everyone

While crucial for leaders it benefits everyone A multilingual population creates a more skilled workforce attracts international business and fosters a more globallyminded and tolerant society

Practical Tips Examples

9 Whats a realworld example of how language skills impact global deals

A business deal negotiated