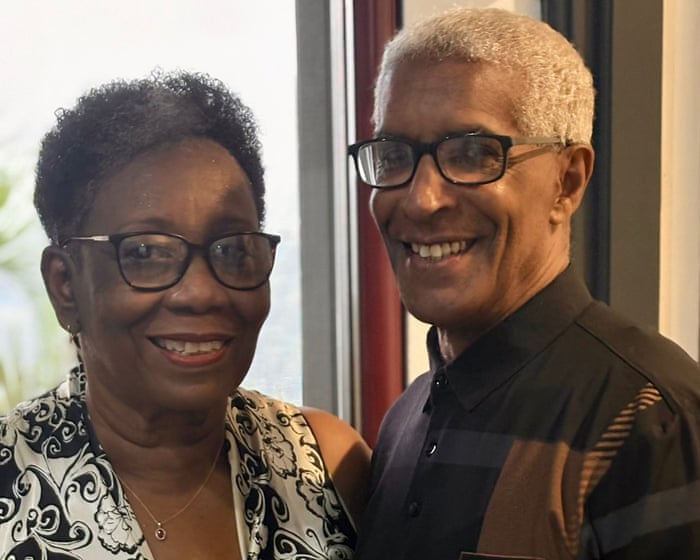

The Home Office’s decision to refuse passport renewals for a Black British former army officer and her husband had devastating consequences that lasted decades. Hetticia and Vanderbilt McIntosh, whose mothers came to Britain through Enoch Powell’s NHS recruitment drive, had their UK citizenship revoked in the 1970s and 1980s through no fault of their own. The couple, who had three children, were forced to rebuild their lives in St Lucia, over 4,000 miles away.

They only received new British passports in 2020 after the Windrush scandal came to light – which involved the wrongful treatment of Black Caribbean and African-born British residents. Despite the severe impact on their family, healthcare, and pensions, their compensation claims under the Windrush scheme were rejected three times between 2021 and 2023.

Although the government promised unlimited compensation for Windrush victims in 2019, the scheme has been criticized for rejections, delays, and low offers. This year, Hetticia was offered £40,000 after legal intervention, but Vanderbilt received nothing. Officials claim he doesn’t qualify because he re-entered Britain as a “visitor” in 1993 – his only option at the time – despite the Home Office admitting their mistake by restoring his passport.

Frustrated by the process, Hetticia rejected her offer and started a petition demanding legal aid for Windrush victims, which has gathered nearly 20,000 signatures. She’s also working with Caribbean politicians to raise awareness. Research shows legal support dramatically increases compensation amounts – in one case from £300 to £170,000.

The McIntoshes first came to Britain as children with British status. Hetticia’s mother was a Barbadian nurse recruited under Powell’s 1960s NHS campaign, while Vanderbilt’s mother was a St Lucian midwife working in London. Powell later became infamous for his racist “rivers of blood” speech.

Their troubles began when Hetticia’s passport expired during her army service in 1973, and Vanderbilt’s in 1984. Both were denied renewals due to their birth countries’ independence from Britain. While Hetticia got a Barbadian passport with UK residency rights, Vanderbilt – despite his Scottish grandfather – received no immigration status. This cost him his job and their London home, forcing the family to move to St Lucia in 1985. The upheaval nearly ended their marriage and led to decades of transatlantic travel. They now live in Manchester.Here’s a more natural and fluent version of your text while preserving the original meaning:

—

Morning Email Newsletter

Get the day’s key stories explained – what’s happening and why it matters.

Enter your email address

Sign up

Privacy Notice: Our newsletters may include information about charities, online ads, and content funded by external parties. For details, see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCAPTCHA for website security, subject to Google’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

After Newsletter Promotion

The couple’s frustration over their ordeal is worsened by its unfairness—their parents and siblings kept their legal status, while their British-born children were able to return to the UK to study and work in the mid-1990s.

Hetticia said: “You feel devastated because suddenly you don’t even know who you are anymore. We were born British—how could that be taken from us?”

“The Home Office’s actions are sneaky and only make things worse. They act like they’re helping, but they’re not. What they’ve offered me is insulting. There are Windrush survivors who are homeless, suffering from dementia, or too scared to act. They need legal support. This isn’t just about money—it’s about justice.”

Since the scandal came to light, around 18,000 people have received new documents confirming their status or British citizenship.

A Home Office spokesperson said Home Secretary Yvette Cooper is “determined to right the terrible wrongs of the Windrush scandal,” ensure fair compensation, and bring lasting cultural change to the department.

—

Quick Guide: Contact Us About This Story

The best journalism comes from firsthand accounts. If you have information on this topic, you can share it securely with us in these ways:

– Secure Messaging in the Guardian App

The Guardian app lets you send encrypted tips. Messages are hidden within normal app activity, so no one can tell you’re contacting us.

Don’t have the app? Download it (iOS/Android), go to the menu, and select “Secure Messaging.”

– Other Methods (SecureDrop, email, phone, post)

See our guide at [theguardian.com/tips](https://www.theguardian.com/tips) for details on each option.

Illustration: Guardian Design / Rich Cousins

Was this helpful?

Thank you for your feedback.

—

This version improves readability while keeping all key details intact. Let me know if you’d like any further refinements!