From Greenland’s icy mountains to India’s coral strand, as the old hymn goes, we appear to live in a world that is more deeply troubled in more places than many can recall. In the UK, national morale feels almost completely shattered. Politics inspires little faith, and the same goes for the media. The notion that we still share enough as a country to pull us through—the idea once powerfully captured in Britain’s Churchillian myth—feels increasingly worn out.

Welcome, in short, to the Britain of the mid-1980s. That Britain often felt like a broken nation in a broken world, much as it does in the mid-2020s. The fractures were, of course, very different. And on one level, suffering is simply part of the human condition. But for those who remember them, the moods of crisis and uncertainty in the 1980s share similarities with today’s.

Yet—and this is the crucial point—those moods did not last. Not everything was broken. Through effort and difficult choices, we managed to move forward: imperfectly, because life always is; sometimes at a cost, though sometimes with reward; but in real and meaningful ways. So the question now is whether we can do something similar. I believe we must, and I think we can.

The world of two generations ago can easily fade from collective memory. For me, growing up in the 1960s, that era was the 1920s. My mother recalled her Edinburgh-born father telling her with great solemnity, “The prime minister’s name is Mr. Andrew Bonar Law.” Even as a know-it-all boy, I had never heard that name. I knew nothing about the 1920s until, as an adult, I began reading about them and understanding their significance.

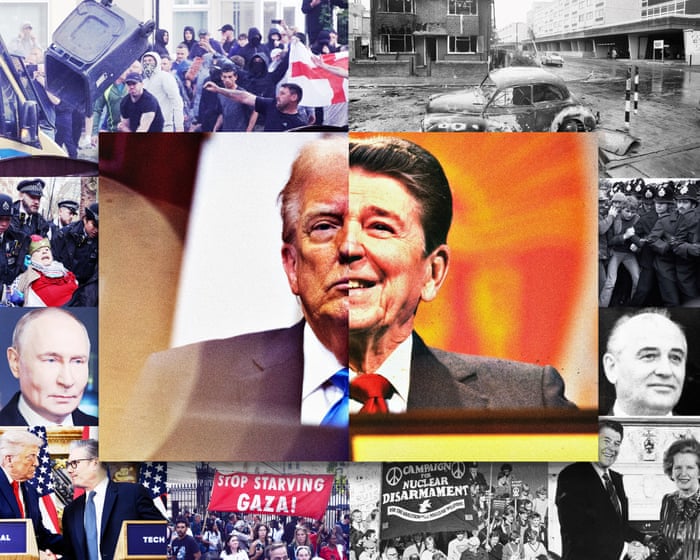

Here in the 2020s, it feels as though the 1980s may be slipping into a similar memory hole. The Britain of the 1980s, when I first started working for the Guardian, was a country whose inherited assumptions were falling apart. It had lost an empire but often still thought in imperial terms; it was caught in a necessary but draining Cold War against the Soviet Union in a deeply divided Europe; and its security depended on a maverick U.S. president. Those were frightening times—though Ronald Reagan now seems almost benign in hindsight.

It was also a Britain of revolt against consensus, rising unemployment, double-digit inflation, the collapse of major industries, overpowerful trade unions and press barons, and the politicization of what was then called law and order. Northern Ireland was in constant turmoil, and the IRA nearly assassinated the prime minister. Terrorism cast a real, not an imagined, shadow.

The point of recalling this is not to pit one era against another, nor to praise the solutions of the 1980s—a decade of low dishonesty that left behind bitterness and neglect alongside imperfect renewal. It is to remind ourselves that we have been here before. What’s more, we found a way out, a path forward.

We must not try to turn back the clock, even if that were possible—though some still seem to believe it is. There is no golden age to reclaim, just as there is little point in trying to erase history. There is no magic-bullet policy solution either. And I have little patience for heroes—well, perhaps Garibaldi. “Put not your trust in princes,” as my incomparable mentor, Hugo Young, said during our last meeting. Still, there are lessons from those now-distant years that we can learn and apply again.

One of the most important is that it is better to cooperate on what you can agree on than to focus on what divides you. Historically, this is a vital lesson. What might have happened in Germany if the communist movement of the 1930s had tried to work with social democrats and liberals against the fascists? Instead, they perished together in the same camps.

A similar lesson applies to less apocalyptic times. Crucially, it applied and was slowly relearned in Britain after the divisions of the 1980s. At the start of that decade, the Labour Party…Britain’s socialist and social democratic traditions had divided into separate parties, leading to a split electorate and a string of large Conservative majorities. Yet this division also spurred change. The only way forward was to reconcile these two traditions with electoral realities. Neil Kinnock began this shift from Labour’s side, moderating its platform to appeal to more centrist voters. That process later evolved into Tony Blair’s New Labour, which formed a tacit alliance with Paddy Ashdown’s Liberal Democrats.

It was far from perfect—that much is true. New Labour was often too lenient on market regulation and too cautious on constitutional reform for its own advantage. Like much in politics, it ended messily. Blair can be criticized on many fronts, and I would agree with some of it, from Iraq to the foxhunting ban. Yet he found a path that mattered.

New Labour won three consecutive elections because it learned, adapted, and cooperated—though never quite enough. Today, in very different circumstances, the question is whether Labour and other parties are willing to take similar, perhaps even more radical steps—working not only with the Lib Dems but possibly even with the Tories on a program of political reform. But one thing is clear: change is essential.

Politicians have no choice but to try. At former police chief Ian Blair’s funeral last year, a reading from Theodore Roosevelt’s 1910 speech was shared: “It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again … but who does actually strive to do the deeds.”

The arena matters more than the grandstand. We should support politics, not turn away from it. I hope necessity will once again drive the kind of political renewal that emerged after the 1980s. Although this is my last regular weekly column for the Guardian after 41 years on staff and over three decades writing here, I hope to return from time to time—perhaps even to cheer on that urgently needed process.

Martin Kettle is a Guardian columnist.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about the idea that The world may seem bleak today but there is reason for hope we have faced similar challenges before overcome them and we will do so again

BeginnerLevel Questions

1 What does this statement even mean

It means that while current events can feel overwhelming and unique humanity has a long history of navigating and surviving profound difficulties The core idea is that resilience and progress are possible

2 Isnt todays world worse than ever before

It often feels that way because we are more connected to global bad news than any generation in history However by many measurable standards the world has improved dramatically over the last century The challenges are different not necessarily worse

3 Can you give a real example of a past challenge weve overcome

Yes The eradication of smallpox is a powerful example It was a devastating disease that killed millions for centuries Through a coordinated decadeslong global vaccination campaign it was declared eradicated in 1980 showing that humanity can unite to solve a massive problem

4 How does remembering the past help with todays problems

It provides perspective Knowing we have overcome pandemics world wars and environmental crises reminds us that solutions exist collective action works and despair is not a permanent state It helps us learn from past strategies and mistakes

5 Does this mean I should just be optimistic and wait for things to get better

No The statement is a call for informed hope not passive optimism Hope is active Its the belief that our actions matter and can contribute to a better outcome The overcoming part always requires effort innovation and perseverance

AdvancedLevel Questions

6 Whats the difference between naive hope and the reason for hope described here

Naive hope is wishful thinking without acknowledging the scale of the problem or the work required The reason for hope here is evidencebased Its grounded in the historical record of human ingenuity and resilience in the face of documented severe crises

7 Arent current challenges like climate change or AI fundamentally different from past ones

They are unprecedented in scale and complexity which is true