Lionel Richie strolls into the hotel meeting room at 6:20 p.m., spreading his arms wide. “Good morning, everybody,” he says in a smooth southern drawl. He isn’t joking. Richie, 76, is on tour in Budapest and living on rock ‘n’ roll time—or rather, the schedule of a legendary soul balladeer. The singer-songwriter, who has sold over 100 million records in his six-decade career, has just woken up. “That bed was telling me, ‘Stay here, Lionel, you’re looking goooood.'”

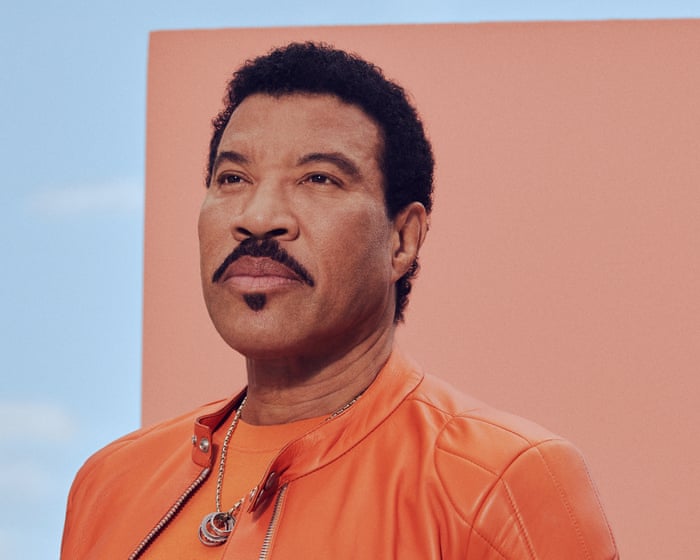

He introduces me to his girlfriend, Lisa Parigi, a Swiss entrepreneur. Parigi is in her mid-30s, stunning, friendly, and young enough to be his daughter—or even his granddaughter, if you stretch it. But to be fair, Richie looks fantastic. As a young man, he was all chin and mustache; now he’s simply handsome, surprisingly tall, with a posture that’s almost military. Parigi leaves us to talk.

Richie is known for his warmth. He doesn’t just invite you to the party—he makes you feel like he’s thrown it just for you. Within seconds of learning I’m from Manchester, he’s sharing stories of his visits there. “Everyone in Manchester would start preparing for the concert three days early. They’d go to the pub the first day, then again the second day, and on the third day, they’d say, ‘Now we’re going to the concert.’ At one point, I thought they didn’t even realize it was me on stage. They were having their own party. They’d take over the show, do soccer chants, and in between, they’d sing ‘Three Times a Lady’ again. And I’d think, wait a minute, I’m not singing that right now. Oh my God, I have so many great stories.”

I know he does—I’ve just read his memoir, and it’s packed with them. He’s worked with everyone: Marvin and Stevie, Quincy and Michael. One moment, he’s getting career-changing advice from Sammy Davis Jr., the next he’s taking Nelson Mandela clothes shopping in LA.

But his family’s influence is even more significant. He grew up on a Black American university campus in the deep south, an unusual background for a person of color born in the 1940s. He says the media has often overlooked this because it didn’t fit their expectations of his story. It’s a fascinating tale. Richie has a way of being present at major moments in music and civil rights history, whether as an active participant, a bystander, or through connections with girlfriends. While we know him for his upbeat attitude, he’s also faced some deep lows.

His story begins in Tuskegee, a small campus town just 38 miles from Montgomery, Alabama, often considered the birthplace of the civil rights movement. Tuskegee was a middle-class Black community where everyone took pride in their education and the city’s political history, Richie explains. From a young age, he learned about Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute and an advocate for African American economic self-sufficiency through vocational education, and scientist George Washington Carver, who transformed southern agriculture and promoted sustainable farming.

Richie’s mother, Alberta, was a school principal, and his father, Lyonel Sr., was a systems analyst for the U.S. Army. His maternal grandmother, Adelaide Mary Foster, a classically trained pianist, was the granddaughter of an enslaved woman named Mariah and the plantation owner Dr. Morgan Brown. In his will, Brown granted freedom to Mariah and her son, John Lewis Brown, who later became the head of a Black fraternal order dedicated to education. Richie and his family grew up in his grandparents’ beautiful home, which had once been faculty housing for the institute.My house was given to my family by its original owner and close friend, Booker T. History was rich and ever-present in our family.

Lionel Richie is pictured with his parents, Alberta and Lyonel Sr, and his sister, Deborah.

“The level of education was so profound that you couldn’t help but absorb it. What I loved about Tuskegee was that failure was not an option. Surrounded by the airmen, the academics, my grandmother, and her generation, I grew up among these extremely refined, aristocratic black people.”

Richie tells me that as a young man, he couldn’t have been less cool—hopeless at sports and invisible to girls. “Often, people look at artists and assume, ‘He must have been a jock or a ladies’ man.’ I was neither. I was the shyest, almost broken kid.” He was a frightened little boy in awe of his tough, high-achieving father, who imparted so much wisdom to him. Lyonel Sr taught him that it’s normal to be afraid. “My dad had a great saying,” he shares. “‘What’s the similarity between a hero and a coward?'”

I tell him I know the answer from his book.

“Can you tell me?” he asks.

“Both are equally scared. But the coward takes a step back, while the hero takes a step forward,” I reply.

“That’s it!” he exclaims, delighted. He looks at his manager, Bruce Eskowitz, who’s sitting with us. “Bruce, give him an A for this course. Give him two stars.”

A hotel waiter comes to take our order.

Richie orders a cappuccino. I opt for a flat white and a double espresso, having just flown into Hungary and feeling the fatigue.

“Ooooh! In that case, I’ll double him by having one more of these. Hahaha! If he’s going to raise the stakes, I’ve got to keep up with my man. He read the book! So I need to be at my sharpest.”

Richie says that when he was writing his book, he realized he had endless anecdotes to share. The publishers loved them but asked where the substance was. He told them he was the substance—his journey of self-discovery and how he reached where he is today. The story he tells is profound, exploring his inner dialogue with his black identity. How black does he have to be? Who defines that? What are the constraints of being black? And again, who makes that decision?

At eight years old, he had a life-changing experience during a shopping trip with his father to Montgomery. Unknowingly, Richie drank from a whites-only water fountain. Lyonel Sr was confronted by a group of angry white men who repeatedly used the N-word and demanded, “Can’t you read?” Richie expected his father to “kick some ass,” but instead, Lyonel Sr quietly told him to get in the car, and they drove away. Richie felt ashamed of his father’s reaction and couldn’t bring himself to ask about it. Five years later, he brought it up at the dinner table. Lyonel Sr replied, “I had a choice that day—whether to be your father or be a man. I chose to be your father because I wanted to be here to see you grow up.”

There was a Tuskegee anger—some of the smartest people in America were hindered and isolated by racism.

Major civil rights landmarks are woven through Richie’s life, almost by chance. He remembers leaders like Martin Luther King and Malcolm X passing through town. He was a member of Jack and Jill, an organization that nurtured leadership potential in black college-bound kids. At ten, he fell in love with a girl named Cynthia, whom he met through Jack and Jill. Cynthia was clever, with “a grace and a smile that were breathtaking.” Every time he saw her, he froze in her presence. Then she disappeared. Many years later, in 1977, he saw her picture on a TV screen, looking just as he remembered. The news was reporting on a Ku Klux Klan member convicted for the 1963 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, which killed four young African American girls. Cynthia Wesley, 14, was one of them.Richie was well aware of the church bombing and considered it the end of his innocence, but he hadn’t known until then that Cynthia was among the victims.

In 1966, at age 17, he learned about the murder of Sammy Younge, a 21-year-old voting rights activist from Tuskegee. After registering 40 black voters in a single day, Younge stopped at a gas station to use the restroom. The white attendant told him to use the hole “where Negroes go,” to which Younge responded that segregated bathrooms were illegal. The attendant pulled out a gun, fired and missed, and Younge drove off seeking police help, but found none. He returned to the station to stand up for his rights. That night, Younge was discovered dead behind the gas station, killed by a single gunshot to the head. The attendant was acquitted after claiming self-defense. This was yet another wake-up call for Richie.

Following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968, Richie recalls, “a heaviness hung over everything.” He began following the Black Panthers, whom he admired greatly. “If Stokely Carmichael had something to say, I wanted to hear it.” By then, Richie was living in Harlem, had joined the Commodores, and was dating a teacher named Sharon Williams, whom he described as “sweet, pretty, and a deep thinker.” She joined the Black Panthers, educated Richie about the struggle, and left for California to join the revolution. Years later, Richie heard that Williams had been in a shootout with police. “I think she died in the shootout. Again, I was on the outskirts.”

Before writing his book, had he realized how personally connected he was to the civil rights movement? “What I didn’t realize was that it formed the core of who I was. At the time, I didn’t see it because our parents made sure to shield us from much of the harsh reality—my sister Deborah, who is two years younger than me and works as a librarian, and I were kept in a bubble.” In 1965, when Martin Luther King Jr. marched to Montgomery, his parents told 15-year-old Lionel he was too young to participate.

Did he want to be part of it? “I was longing to be part of it. And my parents kept telling me it was dangerous.” How did that make him feel? “I was angry because I felt they had excluded me from some of the most significant history. My anger surfaced when I understood what my grandparents and parents had endured. I asked them, ‘Why didn’t you tell me? Why didn’t you involve us in this?’ Their response was, ‘We didn’t want anything to limit your vision of what your future could be. If we had tied you to our anger, you would have been stuck in it too.'” He speaks quietly but with deep passion. Was he aware of that anger? “You couldn’t miss it. Every day I felt the anger because there was a Tuskegee anger.” This was the frustration of some of America’s brightest minds being held back and isolated by racism. Richie points out that civil rights didn’t begin in 1965; he mentions activists from 1936 fighting school segregation and challenges to interstate bus segregation in 1947. If he hadn’t pursued music, Richie could have been a professor of black history. As a child, he even imagined becoming an Episcopal priest.

In 1974, Richie graduated from the Tuskegee Institute with a degree in economics and business, but he had long known that neither field was his calling. In college, guitarist Thomas McClary invited him to join a band called the Mystics. The Mystics later merged with members of a more successful college band, the Jays, and they became the Commodores. They chose the name by randomly opening a dictionary and picking the first word they saw. The word before Commodore was commode, and Richie doubts that the Commodes would have had the same success.The Commodores had been performing for six years by 1974 and were on the verge of releasing their debut album, “Machine Gun,” with Motown. The instrumental title track became a major hit. Lionel Richie, who played saxophone by ear, also sang three songs in their set.

When asked if the rest of the band shared a similar background, Richie replied, “No. For the longest time, I had to deal with one comment from the group: ‘Lionel, you don’t know what it’s like to be poor.’ My response was, ‘Guys, I don’t want to know what it’s like to be poor!'” But the remark struck a chord. “I’d tell them, ‘Stop saying that—you’re making me angry.’ Yet they ended up teaching me the most valuable lesson: how to survive.”

Early in their touring days, he did experience poverty firsthand. “I’d say, ‘I’m hungry, it’s time to eat,’ because I was used to three meals a day. They’d reply, ‘We don’t have enough money for food, Lionel. Just get a jar of orange juice and sip it slowly.’ Then they’d say, ‘You’re going to eat this.’ I’d ask, ‘What is it?’ ‘Chitlins and pickled pig feet.’ Pig feet? My grandmother never had those in the house. It was the best education because it brought me down to reality.”

Feeling newly radicalized, Richie tried to act tough but admits he was naive. “I remember when someone called me the N-word.” The Commodores were scheduled to play a prom at a white high school and arrived 45 minutes late. Three men confronted them, using racial slurs and telling them to leave town immediately. “Instead of fleeing, I exclaimed, ‘Oh my God!’ The guys were yelling, ‘Lionel, get back in the van!’ But I insisted, ‘No, no, no—I’m in the civil rights movement now.’ They urged, ‘Lionel. Get. In. That. Van.'” When one of the men pulled out a Bowie knife, Richie cautiously retreated to the van.

After “Machine Gun,” Richie gradually played less saxophone and took on more vocal duties, writing many of their biggest hits. Their diverse style puzzled critics, but Richie explains it reflected the wide range of music he grew up with. “When I entered the music industry, I noticed they had boxes for everything—’You’re the R&B guy, you’re the black singer.’ I was confused. I wasn’t aware of these categories. My education included country, classical, pipe organ, R&B, blues, and gospel.”

He attributes this variety to his upbringing in Tuskegee, which he estimates had around 2,000 residents during his childhood. “When I started writing, people would ask, ‘Where did “Sail On” come from? That’s a country song. “Three Times a Lady” is a waltz? Where’s the funk?’ Well, it all came from living in that house with the guys on campus. The culture was incredibly rich.”

One of the best pieces of advice he received early on came from Sammy Davis Jr., who told him his career was about to skyrocket and that industry heavyweights would offer him everything he ever wanted and more. Richie was excited, but Davis Jr. cautioned him not to be. He instructed Richie, “Your answer to everything they offer you is no.” When Richie asked why, Davis Jr. replied, “Because I said yes, and I don’t want you to make the same mistakes I did.” Was he warning him against being controlled? “Exactly. That advice alone saved me from years of misery.”

By the early 1980s, Richie was expanding his horizons, writing chart-topping songs for other artists, such as “Lady” for Kenny Rogers.Lionel Richie wrote “Lady” for country star Kenny Rogers and “Endless Love” for Diana Ross, which became her biggest hit as a duet with him. In 1982, he launched his solo career and remained a fixture in the US Top 10 for the next five years, scoring four number-one hits. His music included dancefloor favorites like “Dancing on the Ceiling” and “All Night Long,” as well as sentimental ballads such as “Say You, Say Me” and “Hello,” the latter known for its awkward video depicting a drama teacher falling for his blind student.

When Richie wrote for Kenny Rogers, music promoters and executives questioned his direction, accusing him of losing touch with his roots. This angered him, as he felt he had worked hard to balance his R&B authenticity with pop appeal. He recalls critics in his community saying, “Lionel Richie crossed over and can’t get black.”

Richie joined Motown when Berry Gordy’s soul label was at its peak, allowing him to connect with music legends. The Commodores’ first tour in 1971 was opening for the Jackson 5, where 22-year-old Richie became like an older brother to 12-year-old Michael Jackson. In 1985, they co-wrote “We Are the World,” produced by Quincy Jones, which sold over 20 million copies to aid famine relief in Ethiopia.

Richie describes Jackson as eccentric and chaotic, noting he would wear the same clothes until they fell apart. He and Quincy Jones jokingly called him “smelly,” and Jackson took it in good humor. Once, when Jackson visited Richie’s home, the odor was so strong that Richie gave him a pair of his own jeans and new underwear to change into. Later, he found the discarded clothes in Jackson’s room, looking “like roadkill.”

Although Jackson was acquitted of child molestation in 2005, allegations resurfaced years later in the documentary “Leaving Neverland.” Richie’s daughter Nicole, who gained fame as a reality TV star with Paris Hilton, was Jackson’s goddaughter. She often slept in his room with other children and has stated she never saw anything inappropriate, trusting her parents’ judgment and expressing her love for him.

Richie speaks emotionally about Jackson’s talent and struggles, noting how he missed out on normal childhood experiences like dating and hanging out with friends. He witnessed Jackson’s regimented life, where he’d go straight to the studio after school and work until evening, constantly warned about trusting others.

Richie believes many people took advantage of Jackson but felt unable to advise him, comparing their situation to soldiers in a war dodging the same bullets from unscrupulous individuals.

Despite the challenges, Richie formed incredible friendships and has countless stories to tell. One time, Stevie Wonder scared him by speeding backward down a driveway in his car, prompting Richie to yell in panic. Another memorable moment was when he took Nelson and Winnie Mandela shopping at Neiman Marcus and Saks Fifth Avenue.Preparations were underway for a reception honoring the South African leader. Nelson Mandela once told him, “Young man, I want to thank you for your lyrics and your music. Your songs got me through many years while I was in prison.”

When asked who influenced him most as a songwriter, he named Smokey Robinson, Norman Whitfield, and Marvin Gaye. Each offered guidance in their own way. Marvin Gaye once asked him, “What’s the most important note you’ll ever get, kid?” When he admitted he didn’t know, Marvin replied with a breathy sound, demonstrating how to inhale and exhale. He advised, “Make sure they hear your breathing on the record. It’s not how hard you hit the note, it’s the storytelling.”

As for Smokey Robinson, he described him as the ultimate lyricist with a smooth, teaching manner that made you feel like he could have grown up in Tuskegee. Smokey would say, “Little brother, let me teach you this, let me show you this, let me bring you in,” ensuring that anyone in the room with him gained valuable knowledge.

Among his mentors, his father was the one he often reflected on. His father warned him that life hadn’t tested him yet and that challenges would come in the form of the “five Ds”: divorce, disease, disaster, disgrace, and death. He told him, “A great fighter is not determined by how many punches he can throw, but how many he can take. And you haven’t been hit yet.”

In June 1988, Richie faced his first major blow. He and his first wife, Brenda Harvey-Richie, had quietly separated, and he was dating Diane Alexander, who later became his second wife and mother to his younger children, Sofia and Miles. One day, while at Alexander’s house, Brenda showed up, confronted him about the relationship, and physically assaulted both him and Alexander. The police were called, Brenda was charged, and the incident made front-page news.

He admits he coped poorly with the fallout, describing it as disaster and disgrace hitting back-to-back. He struggled to maintain dignity when his private life was exposed, but his father’s advice echoed in his mind: when life knocks you down, you must get back up.

However, more hardships followed. In 1990, his father passed away, and then he suffered a vocal cord hemorrhage from overuse, threatening his singing career and requiring four surgeries to repair. At his lowest point, he retreated to Jamaica, drinking heavily for five days until he was nearly unconscious, sitting in a deckchair at the water’s edge, waist-deep in the ocean without realizing it.

During his recovery, he confided in Motown executive Skip Miller, saying he had quit the business to avoid a nervous breakdown. Miller responded that he had already had one, which was why he stepped away. He ended up taking a five-year break from work.He looks as if he can’t quite believe it. Richie remarks on how tough the industry is and begins listing its casualties. “Who did we lose? Everyone. Marvin’s gone. You name it, they’re gone. Michael, Prince, Hendrix…”

I ask what he thinks his parents would have made of today’s United States and Trump as president. He responds with a surge of raw emotion. “You know what, I’m glad my dad and that generation aren’t here. It would be tough. I can’t even imagine.” He reflects on the progress they witnessed during the civil rights movement and how it’s now being undone. “And now we’re going back to eliminate it.” He glances at his manager. “Bruce can tell you, I’m having my worst moments because you can’t erase all this progress. I made a statement in 1983 when we were discussing civil rights, and I said, ‘We still talk about that?’ as if to say it’s behind us and we’re focused on the future. Now, here we are 42 years later, still talking about the same thing. But it’s even worse. What I’m seeing now isn’t just regression; it’s the erasure of history.”

When asked if he’s scared for the US, he replies, “Always,” with a hint of desperation in his voice. Would he ever enter politics to challenge Trump? He laughs nervously, then answers firmly, “Never.” Then he recalls that he’s Lionel Richie, the eternal optimist, the lover man, the great unifier who brings the world together through music. He notes that he’s not only African American but also part Cherokee Native American on his grandmother’s side, with a mix of French-Canadian, English, and Scottish heritage. Of course, he was always meant to bring people together. “If you’re waiting for Martin Luther Richie, he isn’t coming. But if you’re waiting for Lionel Richie, the bearer of love, you’ve got me. Back in the day, I thought politics was a great place. But I saw Malcolm, I saw Martin, I saw all the civil rights leaders, and guess what? They didn’t survive it. It’s not survivable. Politics is ugly, it’s nasty, and it’s gotten even worse now because they assassinate your character before you even get in. And I found an avenue that works well for me.”

He shares a story about a Unesco meeting where he was invited to perform and speak about music’s power to bridge differences to delegates from Middle Eastern countries like Israel, Jordan, and Egypt. When he asked why he was chosen, they told him he was the only person everyone could agree on. “I can walk into a room where people don’t like each other, where there’s suspicion. I walk in, and everyone starts smiling. That’s powerful.” Then he recalls a typical gig from the 60s: “Right in the middle of all that craziness, in the third row, there’s a guy from the Klan. A big fan. I can have a conversation with anyone and get the message across better than by standing on a podium, pounding my fist and saying, ‘Follow me!'”

Ultimately, he says the message has to be love, and he’s grateful to be surrounded by it in his own life—with three children, three grandchildren, and his partner, Lisa. Is there any truth to the rumor that they’re thinking of getting married? He makes a shushing sound. “I don’t want to jinx it. I love the rumor,” he says, giggling like a schoolboy. “Keep it like that.”

As I get ready to leave, Bruce asks us not to mention Trump in the article. Richie, however, says he’s fine with what he’s said. But yes, he’s sticking with love over politics. “I’m the pied piper of that whole thing, buddy. ‘I love you’: three corny words that the world needs to hear every day. Wants to hear every day. Now I’d rather…”Then he said, “Let’s go fight the revolution.” “Truly” by Lionel Richie is published by William Collins, priced at £25. To support the Guardian, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs based on Lionel Richies reflections designed with clear natural questions and direct answers

General Beginner Questions

1 What is Lionel Richies main concern about America right now

He is worried about the increasingly bitter and divided political climate where people are arguing more and finding less common ground

2 What does Lionel Richie think is the solution to this division

He believes in the power of love communication and remembering our shared humanity to bridge the divides

3 Did Lionel Richie know Michael Jackson

Yes they were very close friends for many years

4 What song did they work on together

They cowrote the charity anthem We Are the World in 1985 with many other famous artists

Advanced Reflective Questions

5 How does his experience with We Are the World influence his view on todays problems

It serves as a powerful example of how people with different backgrounds and egos can come together for a common humanitarian cause proving collaboration is possible

6 What specific aspect of his friendship with Michael Jackson does he highlight

He often reflects on their deep personal conversations and the unique bond they shared away from the spotlight seeing Michael as a brilliant and complex person not just a superstar

7 Why does he still have faith in love when things seem so polarized

He sees love as a fundamental and active forcenot just a feeling He believes that reaching out listening and showing compassion are practical actions that can break down barriers

8 What common problem does he identify in how people communicate today

He points out that people often talk at each other instead of with each other leading to misunderstandings and entrenched positions rather than solutions

9 Does he offer any practical tips for everyday people who want to help reduce bitterness

Yes his implied advice is to initiate oneonone conversations listen without immediately judging and focus on shared values rather than political labels

10 How does his legacy in music connect to his current message

His songs like All Night Long and We Are the World are about joy celebration and unity His current message is a direct continuation of that lifelong theme applying it to modern challenges