When Anne Geddes started taking her famous baby photographs, she quickly realized she’d need backup babies – sometimes as many as twenty. “Working with babies who don’t know you is incredibly stressful,” she explains. “I remember trying to photograph one baby sitting in a water tank surrounded by water lilies. It took five different babies to get the shot right. One was even named Lily, but she wanted nothing to do with it. She looked at me like, ‘You actually think I’m getting in that water?'”

She describes the behind-the-scenes of her iconic 1991 photo “Cabbage Kids,” featuring twin brothers Rhys and Grant wearing cabbage-leaf hats while sitting in upturned cabbages, looking at each other with slight concern. Her assistant had tied a balloon to a string, lowering it between them and quickly pulling it up the moment they turned – capturing the perfect expression.

“Everything’s changed now; that income stream is gone,” says the 68-year-old Australian photographer from her New York home. Technology has transformed everything. She calls “Cabbage Kids” authentic: “All the props were real. We shot it in my garage. It’s funny – with Photoshop and AI today, people might question if my work was real. But original stories will always matter. That’s why having real people behind photographs is important. AI can’t replicate that.”

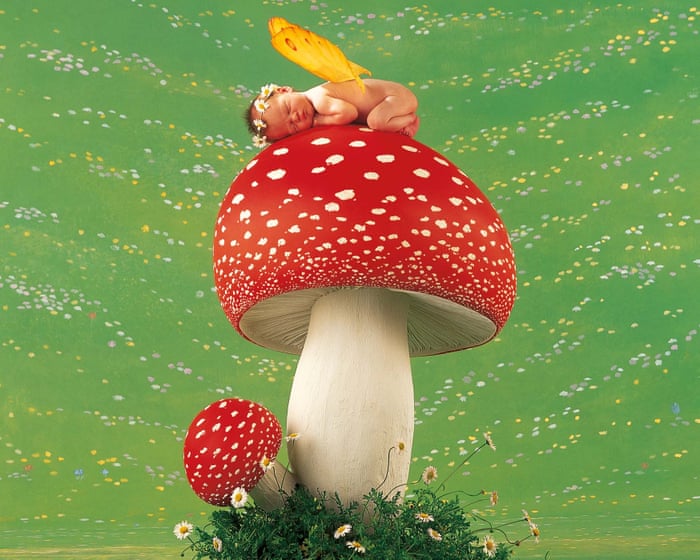

If you grew up in the 1990s, you probably had a Geddes poster on your wall like I did – babies sitting in flowerpots or buckets, or nestled sleepily among peonies, calla lilies, or rose petals. Some dressed as bumblebees or fairies, napping on autumn leaves. The images are whimsical, dreamlike, and sometimes downright strange. Yet they have that rare quality of appealing to children without being childish – and they’re making a comeback, often ironically, on social media.

Her work appeared everywhere – from Hallmark cards to Vogue Homme covers, Dior ads, and even a 2004 book with Céline Dion (featuring the singer holding a baby sleeping inside an amniotic sac). Her career peak came with an appearance on The Oprah Winfrey Show: “Oprah came out holding two bumblebee-dressed babies, and we shot up the New York Times bestseller list!” For many millennials, her cultural moment came when Friends character Janine (played by Elle Macpherson) decorated Joey’s apartment with Geddes’ “Tayla as a Waterlily” photo.

Geddes is striking – silver-haired with high cheekbones and glowing skin, resembling a backwards-cap-wearing Meryl Streep. She sits before a simple backdrop, warm yet slightly reserved, thoughtfully discussing bumblebee costumes and lily pads.

This month marks nearly 30 years since her “Down in the Garden” series – photographs of babies among flowers and nature – some of which will appear in her first retrospective at Germany’s New Art Museum in Tübingen. Among 150 images are identical triplets sleeping in the hands of Jack, a school groundskeeper (whose hands also cradled premature baby Maneesha in a famous 1993 photo). For decades, people have told Geddes they keep this hopeful image on their refrigerators.

Another photo features Tuli and Nyla. Geddes had two studio days, many babies, and a giant Polaroid camera. “I had no props, but you need some plan when working with babies – you have to move fast,” she says. When Nyla started fussing, Tuli rocked her and whispered comforting words.She seized the moment.

Geddes describes her simpler, prop-free photos as her “classic work,” while the iconic baby-in-flowerpot shots are what people recognize—those of us who grew up with them. “After Down in the Garden was published, it was all about the pots,” she says. “Like I had a flowerpot tattooed on my forehead. People always ask for them! But I do other things too. What excites me now is showing that other work. This exhibition is the first time anyone’s really asked me to do that.”

Despite selling over 10 million calendars and nearly twice as many copies of her seven coffee-table books (for comparison, Fifty Shades of Grey sold fewer copies in its first decade), Geddes hasn’t always been taken seriously in an industry dominated by big-name photographers like Bailey and Rankin. Is it snobbery? “It’s a bit of a boys’ club,” she says. “Men would say, ‘I used to shoot babies, then I moved on to landscapes.’ I never understood that. To me, babies are magical.”

The reaction to her baby photos has sometimes been frustrating. “People called me a one-trick pony,” she says. “But I’m just as passionate about photographing pregnant women or new mothers—it’s just that people don’t talk about that as much.” Now, she’s more drawn to capturing the “promise of new life, the miracle of pregnancy and birth,” and hopes the exhibition will highlight that. “Europeans have to say, ‘This is amazing,’ before Americans take notice. It always works that way.”

Born in 1956, Geddes grew up on a vast ranch in Queensland with four sisters. Photography wasn’t part of her childhood—”I only have three photos of myself before age two, none as a newborn.” As a teen, she loved Life magazine and the idea of storytelling through images. Still, she worked in television before discovering the “magic” of the darkroom.

After meeting her husband, Kel, they moved to Hong Kong, where she finally picked up a camera. “I thought, ‘I’ve got stability—now’s the time.’” She started photographing families, borrowing her husband’s Pentax K1000.

Back in Australia, pregnant with her second daughter (now 40), she began her signature baby portraits. In a studio, she could control every detail, crafting elaborate sets in her garage. Many shots happened by chance—like the day a six-month-old named Chelsea arrived, and an empty flowerpot inspired an iconic image. She lined it with fabric for comfort, and months later, sent the photos to a greeting card company. That was the beginning.

Early on, she’d take any baby who came along. But she learned to be selective: “Under four weeks is ideal. If they’re fed and warm, they’ll sleep beautifully.”She particularly enjoyed photographing six- and seven-month-old babies. “At that age, they can’t move around yet, but they’re starting to sit up and see the world from a whole new perspective. Plus, their oversized heads on tiny bodies are just adorable,” she explained.

As her reputation grew, clients began making more demanding requests. “The higher your rates, the more people expect you to perform miracles with cranky two-year-olds,” she noted. Some enthusiastic parents would even call from the hospital after giving birth, saying, “I’ve just had the most beautiful baby!” to which she’d simply reply, “Okay, sure, let’s do this.”

Emma, shown holding baby Thompson in the photograph by Anne Geddes, always ensured parental consent for images used in calendars, posters, books, and magazines. Parents were present during every shoot. “To me, a newborn baby in its natural state is perfection,” she said. “They represent humanity at its purest – good people at the beginning of their journey. That’s what I wanted to capture. When you see the tyrants causing chaos in politics, you wonder: they were once innocent newborns too. What went wrong? Why didn’t their mothers teach them better manners?”

Her artistic inspiration came from May Gibbs’ 1918 Australian children’s book “Tales of Snugglepot and Cuddlepie,” about adventurous bushland creatures. “Every photographer needs their own visual style – this became mine,” she said. Despite the kitschy nature of her work, she achieved remarkable success. “My subject matter has never been considered ‘art’ throughout my career, but that wasn’t the point. I was creating children’s stories, not serious artwork.”

When asked if modern privacy concerns would make her work more difficult today, she disagreed: “While many debate about sharing baby photos online, my work doesn’t personally expose the children.”

Geddes still identifies her photographs by the babies’ names, maintaining contact with some subjects. She recently sought to reconnect with now-adult subjects from thirty years ago, many of whom have become parents themselves.

After our conversation, I found myself looking at photos of my sleeping baby in the next room. Why are we so drawn to images of babies – not just our own? Geddes shared an anecdote: When she nearly won a major New Zealand portrait award, a Kodak executive told her, “Thank goodness you didn’t win – who would want a baby photo in their boardroom?”

Anne Geddes’ retrospective exhibition “Until Now” runs from August 16 to September 21 at Art 28, Neues Kunstmuseum Tübingen, Germany.

FAQS

### **FAQs About “We Put the Baby in a Flowerpot!” – Anne Geddes’ Iconic Photos**

#### **1. Who is Anne Geddes?**

Anne Geddes is a world-famous photographer known for her whimsical, heartwarming images of babies, often posed in creative settings like flowerpots, gardens, and costumes.

#### **2. What’s the story behind the “baby in a flowerpot” photo?**

Geddes wanted to capture the beauty and innocence of newborns in a playful, natural way. The flowerpot idea symbolized growth and new life, making it a timeless image.

#### **3. Were the babies comfortable in those poses?**

Yes! Geddes always prioritized safety and comfort. The babies were gently positioned, often asleep, and closely monitored by parents and assistants.

#### **4. How did Anne Geddes come up with such unique baby photos?**

She drew inspiration from nature, childhood nostalgia, and the idea of celebrating new life. Her creativity turned simple concepts into iconic art.

#### **5. Were the flowerpots real or props?**

Most were custom-made props designed to safely hold the babies while looking like real flowerpots.

#### **6. Did parents volunteer their babies, or were they models?**

Some were professional baby models, but many were just everyday parents who loved Geddes’ work and wanted their child to be part of it.

#### **7. How old were the babies in these photos?**

Most were newborns or just a few weeks old—the ideal age for those curled-up, sleepy poses.

#### **8. Were the photos edited a lot, or were they natural?**

Geddes used minimal editing. The magic came from lighting, props, and the babies’ natural charm!

#### **9. Why did these photos become so popular?**

They were fresh, joyful, and full of emotion—unlike traditional baby portraits. People loved the creativity and warmth they conveyed.

#### **10. Can I take photos like Anne Geddes at home?**

Yes, but safety first! Use soft props, natural light, and never force a baby into a pose. Keep it simple and fun.

#### **11. What’s the most famous Anne Geddes photo?**

The “baby in a flower