Matthew Hutchinson’s memoir, Are You Really the Doctor?, recounts his experiences as a Black doctor in the NHS. It opens in A&E with a patient suffering a thunderclap headache who, despite being in excruciating pain, takes a moment to complain that Hutchinson looks “very scruffy.” Hutchinson notes that he was wearing standard-issue scrubs—hardly an outfit that allows for personal style. He concludes wearily that the patient must have been reacting to something else: his skin, hair, or general “vibe.” This wasn’t exactly a microaggression, but it reflected the assumption that, as a Black man, he couldn’t possibly be an expert. Yet this incident barely registers compared to the deeper bigotry Hutchinson explores in his book—from prejudice faced by doctors to racial and gender biases in medical training, and even life-threatening racism, such as the fact that Black women are four times more likely to die during childbirth.

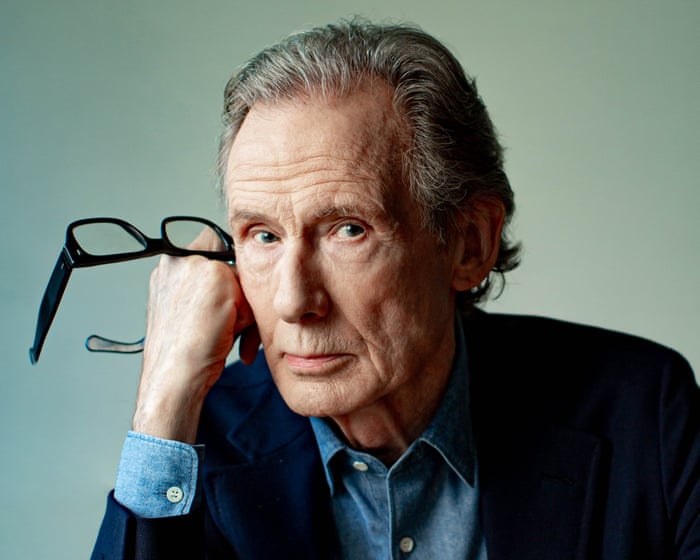

Meeting Hutchinson at the Guardian’s offices in London, he comes across as thoughtful and capable. Even dressed casually in shorts and a T-shirt, he carries an air of professionalism. He says writing a book about race felt necessary, but he’s also spoken to women of color who say gender bias is often a bigger obstacle than race. His wife, Louise, is a GP, and he points out the lack of respect female doctors sometimes face—even from colleagues. He also notes the absence of literature about doctors with disabilities and the barriers they encounter, mentioning he’s met only one hearing-impaired doctor in his entire career.

Hutchinson’s fair-mindedness—stepping back to consider every angle—hints at the kind of doctor he is. It also reflects his chosen specialty, rheumatology, which deals with mysterious, hard-to-pin-down pain. At 38, he’s about to become a consultant.

He also does stand-up comedy, a pursuit that grew out of his years as a senior house officer in the mid-2010s—a time when he felt disaffected with medicine and was searching for other outlets. His comedy started as a left-leaning take on politics, parenting, and life’s absurdities (like Suella Braverman criticizing multiculturalism, or Formula One’s lack of diversity). He sees parallels between comedy and medicine: both involve winning over a room and convincing people you know what you’re doing. His book is often darkly funny—like when a colleague referred to dementia care as “veterinary medicine”—but it doesn’t use humor to soften difficult truths. His detailed descriptions, such as the suffering of a lupus patient, make you feel you’re right there with him.

A major concern during his medical training? Avoiding being placed in areas where far-right political movements were gaining traction.

Hutchinson comes from a family of scientists: both his parents were biochemists (now retired), and his younger brother is an anaesthetist. His father moved from Jamaica to Birmingham at age 19; his mother is Scottish. He grew up in the southeast.He still lives in London, in a neighbourhood that has transformed from a mix of rough and leafy areas to one that’s barely affordable even on two doctors’ salaries. Not far from Eltham, where Stephen Lawrence was murdered, racism was no secret, but it wasn’t until Hutchinson went camping in Cornwall as a teenager that he encountered the open bigotry of rural, monocultural Britain. Some local teens tried to start a fight with him, using the strangely menacing phrase: “What are you doing here, dark horse?”

That experience stayed with him when he decided to become a doctor, because the NHS can send you anywhere in your first year of work. “From almost day one in medical school, one of your main worries is: how do I avoid being sent away? Even if it’s not far across the country, just having to spend a year outside London in a place where Reform is gaining support, St George’s crosses are popping up everywhere, and migrant hotels are being burned down—that’s something you have to think about.” There’s no simple fix. Doctors used to be placed using a complex points system; now it’s done by lottery. Both methods have their critics, and as Hutchinson says, “everywhere needs doctors.” He isn’t looking for an easy answer, just pointing out that in today’s climate, where politicians stir racial tension with coded “concerns about immigration” and endless debates over whose anger is justified, you rarely hear from the Black healthcare workers who have to go and live amid that anger.

In the end, he spent his first year in 2012—foundation year 1, at the bottom of the medical hierarchy—in Essex. “I don’t think I could do now, as an experienced doctor, what I was asked to do in my first placement,” he says. As the most junior doctors, FY1s are often the only ones covering wards out of hours. “Overnight, you’re the only point of contact for about 400 medical beds, which is absurd given how ill these patients are. Roughly speaking, 40 might need urgent care. And it’s you, the most junior person, showing up. It’s improved in some places, so you might have two registrars on overnight. But I’d still say the night shift is about doing the bare minimum for patients already in hospital, just to get through until morning.”

Things have changed since over twenty years ago, when junior doctors were known for brutally long shifts. But every solution seems to create a new problem. Shorter shifts with longer breaks were introduced in the 2016 junior doctors contract in England, acknowledging that even medics can’t function without sleep. Hutchinson found back-to-back night shifts “very mentally destabilising; I get terrified of the idea of death. I’ve had that fear since I was 17 or 18, but I only think about it when I’m sleep-deprived.” Although junior doctors now work shorter shifts, no extra staff appeared to fill the gap, leading to widespread understaffing. Only during the pandemic, “when everyone was pulled from elective care and clinics,” did urgent care suddenly have enough staff. “It was probably some of the best-staffed work I’ve ever done in my career,” he says. But there was a downside, as there often is. “What we’re seeing now is that it was a complete disaster for secondary care. It was as if no other illnesses existed. So you found all these people 18 months later in a bad way because their rheumatoid arthritis hadn’t been properly monitored or treated.”

Cardiology tends to attract people who can be quite blunt, aggressive, and full of themselves. Hutchinson has some pretty sharp opinions about others in the medical field.Some specialties, especially cardiology, tend to attract people who are blunt, assertive, and have a strong sense of self-importance. His early career, first in Essex and later back in London, was filled with run-ins with cardiologists. When I ask if it’s a class issue—given the type of driven, high-achieving students he describes, who often aim for elite schools and competitive fields like cardiac or brain surgery—he says no. Even with more demographic diversity today, the specialty remains intense. Past behavior was worse, he notes, and while people have toned down their language, the underlying attitudes haven’t disappeared. He adds, with a touch of humor, that he doesn’t want to let rheumatologists off too easily either—there are plenty of abrupt ones among them, too.

Between surviving his grueling first year in Essex and returning to London for his second foundation year at a well-resourced, prestigious hospital—which he describes as a place where “pampered professors carve out fiefdoms”—he met his wife at his brother’s party. They now have two children, one starting preschool and the other just four months old. He deeply respects the work of general practitioners like his wife, calling it incredibly difficult. “The idea that you’re expected to distinguish between a common cold and early signs of lung cancer in just 10 minutes is staggering,” he says. “The variety of cases, the short appointment times, and the level of risk they carry are just unreasonable.”

Rheumatology, by contrast, presents its own challenges, particularly in getting patients to describe their pain accurately. In his writing, his own descriptions of pain—from kidney stones to rheumatoid arthritis—are so vivid and precise they read almost like poetry. “The nature of pain is often critically important for diagnosis,” he explains. “You spend a lot of time thinking about its specific qualities. A thunderclap headache feels like being struck with a hammer; cardiac pain is more like pressure or crushing. Sharp, stabbing pain might point to a blood clot in the lungs. And of course, how people describe pain is shaped by their culture, language, and background.”

Within medicine, rheumatologists are often the last resort when other tests come up empty. “It’s closely tied to immunology—a sophisticated, investigative field dealing with rare and complex diseases,” he says. But it can also be frustrating. There are two approaches, he explains: one is to make a binary decision—either the patient has an immune-mediated inflammatory disease and becomes your responsibility, or they don’t, and you move on. “That’s probably what managers prefer, since it’s efficient.”

The other way is to acknowledge that a patient’s condition may not fit neatly into known categories. “If you take the time—even if it means running 20 minutes late—to sit down, talk, and say, ‘I believe you’re in pain. We may not have all the answers yet, and I don’t want to prescribe something that could make things worse, but I’m committed to working with you,’ that can mean everything.” For patients, simply feeling heard and validated is often more meaningful than being dismissed because no cause can be found.

Yet taking this holistic approach means constantly facing the limits of what medicine can solve. “You can offer the best possible care, but you’re still…”You probably won’t be able to do everything else that’s required for your patients to truly feel fulfilled and happy. For example, you can’t fix the elevator in their building so they don’t have to climb 20 flights of stairs with rheumatoid arthritis. That’s another source of frustration.

Medicine has to work within the conditions of the world around it, often with very little influence over that world. Take a cancer diagnosis—on the surface, it might seem like an equalizer. But if you compare a multi-millionaire and someone living in public housing, sure, they both have cancer, but the environments in which they’re experiencing it are vastly different. Their worries about their children, their ability to attend appointments—these small details can change how someone engages with their treatment.

These days, Hutchinson spends three days a week in his clinic and two days researching rheumatology and internal medicine at the Crick Institute in King’s Cross. If he has any nerves about his book coming out, it’s mainly about whether cardiologists can take a joke. Being involved in comedy and publishing has made him appreciate some of the good things about medicine. “When I see what other people go through in their jobs, the stability and career progression in the NHS look great.”

On the verge of becoming a consultant—and presumably bracing for a new round of “are you really the consultant?”—he’s determined not to change his bedside manner or overall approach to the job. “A lot of people, when they become consultants, completely change the way they dress and suddenly show up in a brand new suit. I imagine that’s mainly cardiologists.”

Are You Really the Doctor? My Life as a Black Doctor in the NHS by Matthew Hutchinson is published on September 4 (Blink Publishing, £22). To support the Guardian, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs based on the topic framed in a natural conversational tone

General Beginner Questions

Q What is this quote Youre the only person 400 hospital patients can turn to referring to

A It refers to the dangerously high number of patients a single junior doctor is often responsible for overnight in an NHS hospital highlighting a severe lack of staffing

Q Who is Matthew Hutchinson

A He is an NHS doctor who publicly spoke out about the immense pressure and unsafe working conditions that junior doctors face using this powerful quote to illustrate the problem

Q What does he mean by which is ridiculous

A Hes stating that this situation is absurd unsafe and completely unreasonable Its not a sustainable or safe way to run a healthcare system for patients or staff

Q Is this a common problem in the NHS

A Yes unfortunately While the exact number of patients per doctor varies being responsible for an overwhelming number of very sick patients is a frequent experience reported by many junior doctors especially during night shifts

Intermediate Impact Questions

Q What are the main dangers for patients in this situation

A The main dangers are delayed care missed diagnoses and medication errors When one doctor is stretched so thin they cannot give each patient the timely and thorough attention they need which can lead to serious harm

Q What are the dangers for the doctors themselves

A Doctors face extreme stress burnout and moral injurythe psychological distress from being unable to provide the standard of care they know is right This leads to high rates of mental health issues and many doctors leaving the profession

Q Why is this happening Isnt the NHS funded to prevent this

A A combination of factors a shortage of trained doctors and nurses rising patient demand budget constraints and difficulties in retaining existing staff who are burning out

Q Couldnt a doctor just call for help if theyre overwhelmed

A Often there is no one to call The quote implies they are the help Senior doctors may be on call for multiple hospitals or dealing with their own critical cases leaving the junior doctor as the sole point of contact

Advanced ActionOriented Questions