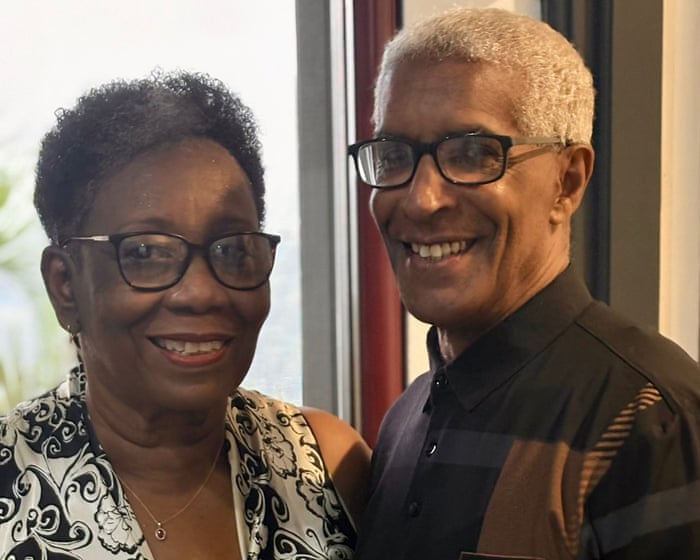

Two aging street lamps cast a faint glow on the dark road leading into the woods outside Mazée village. This is a common sight along the narrow country roads of Wallonia in southern Belgium. “Having lights here makes sense,” says 77-year-old André Detournay, a resident for forty years. “I walk here with my dog, and it makes me feel safe and offers some protection from theft.”

From space, Belgium shines at night like a Christmas ornament. It is one of Europe’s most light-polluted countries, with the Milky Way rarely visible except in the most isolated areas.

But in the coming months, these lamps outside Mazée in the municipality of Viroinval will be permanently switched off. This is part of a bold project to remove 75 unnecessary streetlights in this part of Wallonia.

Across Europe, unnecessary lighting is being eliminated, largely to protect nature. Over the past decade, growing research has shown that artificial night light harms a wide range of species—including insects, birds, and amphibians—disrupting their feeding, reproduction, and navigation.

Detournay is not pleased. “I’m for frogs. I dug two ponds for them,” he says. “But near a village, we need lights. You’d have to show me clear proof that this significantly increases biodiversity here to change my mind.”

The project began in 2021. A Wallonia public administrator estimated that 6% of the 8,000 streetlights in the Entre-Sambre-et-Meuse national park—a protected landscape of forests, rivers, and wetlands near the French border—were pointless. These lights were more than 50 meters from the nearest building (often on roads between villages with little foot traffic) and less than 50 meters from a Natura 2000 site, areas deemed of the highest value to nature.

The national park has allocated €308,000 to restore nighttime darkness, treating it as beneficial for nature in the same way as restoring a pond or woodland. Between now and August, dozens of streetlights are being removed by the municipality’s electricity grid operators.

“We can’t tell an elderly lady that we’re prioritizing bats over her,” says Nicolas Goethals, who leads the project, stressing that public safety remains critical.

Some, however, remain unconvinced. Jacques Monty from the Viroinval municipality is up an eight-meter pole in a cherry picker, untangling wires and metal to remove a light near the village of Nismes, where nearby limestone caves are a bat hotspot. Monty has worked for the municipality for 35 years, and until now, his job has always involved maintaining lighting. “This might be good, but we need to ensure it doesn’t compromise people’s safety—that’s my priority,” he says.

The public debate over streetlights is straightforward: they make people feel safer, which is the main objection from residents in Wallonia. But research tells a more complicated story.

While lighting increases people’s sense of safety and willingness to walk at night, it doesn’t always mean they are actually safer. One study on reduced street lighting in England and Wales found no significant link to changes in crime or road collisions. Other reviews have found inconclusive evidence that lighting reduces crime, and data on the subject remains mixed.Efforts to reduce road collisions present a mixed picture. “Seventy-five streetlights might not seem like much, but you have to start somewhere,” says Goethals, who has organized local talks, night walks, and sent letters to win people over to the project. “It’s not right that lights are on all night for everyone when they’re not being used. Darkness should be the norm—it’s nighttime!” he argues. If people want to walk on rural roads, he suggests they light themselves with reflective vests and torches.

The harmful effects of light pollution on nature, human health, and plants are clear. Experts say light pollution should be treated as a serious threat to nature, similar to habitat loss or chemical contamination. More than half of all insects are active at night. In France, public lighting kills an estimated two trillion insects each year, either from exhaustion or by making them easy prey for predators.

This is a global issue. While the electric lightbulb, invented 150 years ago, transformed human life, today 80% of the world’s population lives under light-polluted skies.

Across France, thousands of towns turn off public lighting overnight to save energy and cut light pollution. The EU offers guidance on creating dark corridors for wildlife and reducing artificial light at night. In the UK, campaign groups are raising awareness, and several U.S. cities are working to reduce sky glow. In April, Goethals is teaming up with French colleagues to expand darkness infrastructure into other parts of Europe. “This is just the beginning—real darkness infrastructure will grow from here,” he says.

Elsewhere in the park, another infrastructure project shows what disused poles can become. Old electricity pylons—once a danger to wildlife—are being adapted to support the return of white storks. In 2011, white storks were relatively rare, but by 2025 nearly 800 were recorded in the national park, with numbers rising each year.

These large white birds naturally nest at the tops of tall trees, but in landscapes shaped by humans, an old pylon serves as a good substitute. Each metal stork nest costs €500, with a goal of installing 30 by this summer. Branches and fake droppings are added to each nest to make it appear already approved by a previous resident. Unlike removing streetlights, this work is universally welcomed. “People love these birds. I’ve never met anyone who doesn’t enjoy seeing them in their nests,” says Goethals.

Though this experiment on Belgium’s rural roads is modest, it reflects a larger shift. For over a century, humans have tried to illuminate every corner of the night. Now, a growing movement is working to bring back the dark.

Frequently Asked Questions

Of course Here is a list of FAQs about the Normal should be darkness initiative in Belgiums High Fens National Park designed in a natural conversational tone

Beginner General Questions

1 What is the Normal should be darkness project

Its an initiative in Belgiums High Fens National Park to permanently switch off unnecessary public streetlights The goal is to restore natural darkness for wildlife human health and stargazing

2 Why are they turning off the streetlights Isnt that unsafe

The core idea is that constant artificial light isnt natural or necessary in a protected wilderness area They are only removing lights deemed nonessential for safety The aim is to make darkness the normal state not light

3 Which park is doing this

The High Fens National Park a large nature reserve in eastern Belgium

4 Will all lights be turned off

No Lights considered essential for road safety at key intersections or hazardous spots will remain on The project targets lights along rural roads and in forested areas where they provide little safety benefit but cause significant ecological harm

Benefits Reasons

5 What are the main benefits of less light pollution

For Wildlife Helps nocturnal animals navigate hunt and reproduce naturally It prevents disorienting migrating birds

For Humans Promotes better sleep by protecting our natural circadian rhythms It also reveals the stunning night sky

For the Environment Saves energy and reduces carbon emissions from producing electricity

6 How does light pollution affect animals

It can confuse them For example baby sea turtles head toward city lights instead of the moonlit ocean moths circle bulbs until exhausted and birds can collide with lit buildings during migration

7 Is there a benefit for people visiting the park

Yes Visitors can experience true darkness and see a spectacular starry sky which is becoming rare Its also a quieter more immersive natural experience

Practical Concerns Problems

8 Wont this make driving or walking at night dangerous

Authorities are conducting safety analyses The plan involves improving alternative safety measures like better road markings and