Every November, the leading figures of French literature gather in the upstairs room of a classic Parisian restaurant to choose the year’s best novel. The ceremony is formal and steeped in tradition, right down to the restaurant’s menu of timeless dishes like vol-au-vents and foie gras on toast. In photos from the judging, the panelists wear dark suits, each with four glasses of wine at their place.

Winning the Goncourt Prize, as it is known, can secure a writer a place in the pantheon of world literature, joining a lineage that includes Marcel Proust and Simone de Beauvoir. The prize also brings significant financial rewards. As the most prestigious award in French literature, the Goncourt guarantees prime placement in bookstore windows, international rights deals, and lasting prestige. By one estimate, winning leads to nearly €1 million in sales in the following weeks.

In November 2024, the Académie Goncourt awarded the prize to a novel by Kamel Daoud, a celebrated Algerian writer living in France. His win came at a tense moment between France and its former colony. Their already difficult relationship had been strained by Algeria’s increasing political repression at home and by France’s involvement in the dispute between Algeria and Morocco over Western Sahara. (France has sided with Morocco, which claims sovereignty over the territory, while Algeria has supported independence movements there.)

Daoud’s own career has been shaped by this fraught history. Though long a literary star in both countries, he moved to France in 2023, saying he could no longer “write or breathe” in Algeria. His French publisher, Gallimard—one of France’s largest—was barred from the 2024 Algiers book fair without explanation, though many suspected it was because Gallimard had published Daoud’s latest novel, Houris.

Houris tackles a long-controversial subject: Algeria’s civil war, known as the “Black Decade,” a brutal conflict between the government and armed Islamist groups throughout the 1990s. Estimates of the death toll vary, with some as high as 200,000. Civilians were massacred across the country, atrocities often later claimed by Islamist groups.

The period remains delicate to discuss. In 1999, a law offered legal clemency to Islamist fighters who laid down their arms. In 2005, Algeria passed a broader reconciliation law that extended amnesty. But unlike similar laws elsewhere, which often require some form of accountability, this one “allows for official forgetting, without any reflection on the actions of either side,” as one historian explained. “The executioners just went home.”

The reconciliation law is broadly worded, making it illegal “to use or exploit the wounds of the national tragedy to undermine the institutions of the People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria, weaken the state, damage the reputation of all its officials who have served it with dignity, or tarnish Algeria’s image internationally.” The Black Decade is still not taught in Algerian schools. In interviews about his novel, Daoud emphasized the law’s wide reach. The civil war, he said, is “a taboo subject that you can’t even think about.”

Houris, which was not published in Algeria, tells the story of the war through a 26-year-old woman named Fajr, or Aube (Dawn). As a child, she survived a massacre in Had Chekala, a village where a real massacre occurred in January 1998. In the novel, terrorists kill Aube’s family and slit her throat with a knife. The attack leaves her with a large scar across her neck—what she calls her “smile.” To breathe, she has undergone a tracheostomy, a procedure that opens the neck to access the windpipe. She wears a cannula, sometimes hidden by a scarf. “I always choose a rare and expensive fabric,” she says. But her injuries mean that, two decades later, her voice is barely audible. For her, the scar is a mark of history.Many want to forget. “I am the true trace, the most solid sign of everything we lived through for ten years in Algeria,” she says.

The book opens in 2018, with Aube pregnant with a girl she calls her houri—a name for a virgin of paradise in Muslim tradition. Contemplating an abortion, she returns to the site of a massacre. The novel unfolds as an interior monologue between Aube and her unborn child, interrupted by the arrival of Aïssa, a man who has collected stories of the civil war and recounts them like a human encyclopedia. He speaks at length about the Algerian civil war and why it remains a controversial part of the country’s heritage. “There are no books, no films, no witnesses for 200,000 deaths. Silence!” he says. The Goncourt judges praised Daoud for giving “voice to the suffering associated with a dark period in Algeria’s history, particularly that of women.”

Eleven days after the Goncourt ceremony, a woman appeared on an Algerian news show. She wore a blue-and-white striped shirt, her long hair tied in a bun, leaving her neck visible along with a breathing apparatus and cannula. She introduced herself as Saâda Arbane, 30, and claimed that Daoud had stolen her personal details for his bestselling novel. “It’s my personal life, my story. I’m the only one who should decide how it is made public,” she said. For 25 years, she explained, “I’ve hidden my story, I’ve hidden my face. I don’t want people pointing at me.” But Arbane said she had confided in her psychiatrist, telling her everything without filter or taboos. That psychiatrist was Kamel Daoud’s wife.

Arbane is now suing Daoud in both Algeria and France, with separate cases presenting her position from two angles. In Algeria, her case focuses on medical records she claims were stolen from a hospital in Oran and used as research material for Daoud’s book. In France, she is suing Daoud and his publisher Gallimard for invasion of privacy and libel.

Daoud argues there is no basis for these claims, stating that his work draws from many stories of Algeria’s “black decade.” He contends that Arbane is not the real force behind the lawsuits, but rather that they are part of a broader effort by the Algerian government to silence prominent critics of the regime.

In France, where news about Algeria is closely followed, the cases have become entangled with larger questions about history, colonialism, and international relations. One headline read: “Kamel Daoud, from ‘invasion of privacy’ to the Franco-Algerian diplomatic battle.” The legal fight involves notable political figures: Arbane is represented by the prominent human rights lawyer William Bourdon and his associate Lily Ravon, while Daoud’s lawyer, Jacqueline Laffont-Haïk, recently defended former French president Nicolas Sarkozy.

The case against Daoud touches on many questions that haunt the literary world: To whom does a story belong? Is it acceptable to use another person’s story for personal gain? Does the answer change when one person is a man and the other a woman, or when one is famous and the other a victim left almost voiceless by trauma?

But the deeper I looked into what really happened, the question seemed to grow even larger. Daoud’s defense hinges on his persecution by the Algerian state. Yet what kind of behavior can persecution justify?

Daoud is Algeria’s best-known writer. His work has been translated into 35 languages, and he regularly writes for French outlets about Algeria and current affairs. One critic described him as “a brilliant, indeed dazzling, thinker.” Raised by his grandparents in the small Algerian town of Mesra while his father, a policeman, worked in various parts of the country, Daoud was drawn to Islam as a teenager.He was an Islamist but left the movement at 18. “At a certain point, I no longer felt anything,” he later told the New York Times. In his early 20s, he turned to journalism, covering the Algerian civil war. In 1998, he reported on the massacre at Had Chekala, one of several villages where hundreds of people were killed by Islamist forces during Ramadan. Two years later, he started his own column in Le Quotidien d’Oran, the French-language paper in the coastal city of Oran. It was called “Raïna raïkoum,” roughly meaning, “My opinion, your opinion.” He began writing short fiction, and in the 2000s won acclaim for his short books and story collections. “He was very famous,” says Sofiane Hadjadj, his former editor at the Algerian publishing house Barzakh.

In 2010, Daoud wrote a column for Le Monde in which he reimagined the story of the unnamed Arab man murdered in Albert Camus’s existentialist novel The Stranger. He wrote from the perspective of the dead man’s brother, responding to the story told by the novel’s protagonist, a Frenchman named Meursault. The column caught the attention of Hadjadj and his colleagues, who encouraged him to turn it into a novel. They published it in Algeria in 2013.

When the novel, The Meursault Investigation, was republished in France in 2014, it became a sensation. With Daoud’s clever premise, the novel allowed the colonized to talk back to the colonizers by rebutting one of France’s most cherished literary works, itself written by a white Frenchman born in Algeria. The novel also offered a complex critique of Algeria’s postcolonial development. “Kamel Daoud’s novel The Meursault Investigation may have attracted more international attention than any other debut in recent years,” wrote Claire Messud in the New York Review of Books. Daoud received widespread coverage across the English-speaking media. The Guardian called the book an “instant classic,” and the New York Times profiled him at length. In Oran, Daoud was already a star. But after the publication of Meursault, Hadjadj says, “There was an explosion.”

The novel’s success brought Daoud unusual visibility for a writer. In Algeria, an imam accused him of apostasy after a media appearance in which he questioned the role of religion in the Arab world. He also took a prominent place in French culture, writing a column from Algeria for the conservative weekly Le Point, where he opined on everything from immigration to #MeToo. His writing was lyrical, sometimes impressionistic, and often returned to the dangers of fundamentalism of all kinds. “All my work,” he wrote in an introduction to a collection of his columns from the last decade, “insists on one point: ‘Be careful! A country can be lost in a minute!’”

A frequent guest on TV and radio, Daoud was a notable Algerian voice in a culture that often remains dismissive, and sometimes vindictive, toward its former colony. When President Macron made a state visit to Algeria in 2022, he took the time to have dinner with Daoud.

While Kamel Daoud’s star was rising, Saâda Arbane was figuring out how to move past a terrible tragedy. She was born in 1993 in a small town in Algeria to a family of shepherds. In 2000, Islamist terrorists murdered her parents and five siblings. No one knows if there was any motivation for the attack on their town; it’s likely that, as with many during that period, there was none. The terrorists cut Arbane’s throat and left her for dead. She was six years old.

Arbane was first brought to a local hospital, then transferred to Oran, where she spent five months in a pediatric intensive care unit. From there, she was transferred to France, where she received a tracheostomy and was fitted with a cannula. After such an ordeal, “I don’t know that“Many would still be standing,” her aunt told me.

One of the pediatricians in the Algerian health service, Zahia Mentouri, decided to adopt Arbane. Her adoptive family was distinguished: Mentouri had led pediatric intensive care units across the country and briefly served as minister of health and social affairs. Her adoptive father, Tayeb Chenntouf, was a well-known Algerian historian who served on a UNESCO committee on African history. Together, they lived in Oran.

For some time, Arbane could only consume liquids. Although her family hoped surgery might allow her to speak more clearly, it was not possible to reconstruct her vocal cords. The attack left psychological scars as well. A medical report from 2001, after her transfer to France, describes how, at the start of a hospital stay there, her drawings only showed plants surrounded by thorns. When she began drawing people, the same report notes, they all had visible tracheostomies, covered with scarves. (The report is included in Arbane’s evidence for her French trial.)

Arbane struggled in school in Oran. Few people could understand her. At first, she could not even whisper. “Everyone would stare at her cannula,” said one relative. Classmates called her “Donald Duck” because of her fractured voice. Even today, Arbane’s words are not always clear to those who don’t know her well. For this article, I spoke to her twice via Zoom, with her husband acting as a kind of interpreter, repeating what she had said.

Growing up, Arbane almost never discussed what had happened to her. She did not bring it up with her family, several relatives told me, nor did they ask questions. “To be a child with a tracheostomy, to speak with a whisper, coughing through one’s neck, secreting and wiping snot from one’s neck: I was a freak show to kids and to many adults,” she told me.

Her relatives describe Arbane as someone with unusual determination. “She completes every task she starts,” said one family friend. She spent her final year of high school in France. In 2016, she married and had a son, whom she credits with saving her life. She opened a beauty salon in Oran in her late twenties. “She has fairy fingers,” the family friend said.

Arbane found comfort in horseback riding, which reminds her of her biological family, who kept horses. As a teenager, she competed internationally. An article in L’Écho d’Oran about the 2009 Maghreb horseback riding championship, a high-level event, describes how “Saâda Arbane ‘knows the obstacles’; she jumps over them in silence, with determination and elegance.”

In 2015, Arbane began seeing Dr. Aïcha Dehdouh, a respected psychiatrist in Oran who was close to Arbane’s adoptive family. In Arbane’s recollection, she initially went to discuss issues she was having with her mother. Arbane met with Dehdouh in an office at the University Hospital of Oran, sometimes with her mother, sometimes one-on-one. She found Dehdouh easy to talk to, and soon they “talked about everything.” Arbane recalled that Dehdouh took notes during their sessions on pieces of paper, which she placed in a folder. (I attempted to reach Dehdouh via two email addresses and her telephone number, as well as through her husband, but she did not respond to these inquiries, nor to a detailed list of the claims made in this article.)

Arbane’s lawyers contend that the relationship between Arbane and Dehdouh was far closer than is normal between a patient and therapist. They became friends. In texts, Dehdouh wrote to Arbane using the informal “tu” rather than the more formal “vous.” “You’re an angel,” Dehdouh wrote in one message; another she signed “big kisses.” They had sons of a similar age, for whom they discussed organizing outings.The friendship began with the children, through activities like pyjama parties. “The relationship started with the children,” Arbane explained during our conversation. In messages, Dahdouh affectionately called Arbane’s son “mon petit chéri” – my little darling. She sent a photo of herself at the beach with their sons, and another of them standing together by the water. Dahdouh also asked for Arbane’s help in renting out an apartment she co-owned with her husband, Daoud.

Around the end of the Covid pandemic, in 2021 Arbane believes, she met up with Dahdouh and their children. Dahdouh brought her husband along. Despite Daoud’s fame, Arbane knew little about him. “Reading isn’t my thing,” she told me. She felt he seemed surprised by her appearance. Dahdouh later mentioned she hadn’t shared any details about Arbane’s background or the attack she had survived.

According to Arbane, a few weeks later during Ramadan, Dahdouh and Daoud invited her over for coffee. Daoud expressed his desire to write a book about her story. When she declined, he said he would respect her decision, noting there were many similar stories. He gave her a book about Emir Abd el-Kader, a 19th-century Algerian leader celebrated for his horsemanship and his resistance against French colonial forces.

Shortly after, the lawsuit states that Dahdouh invited Arbane’s adoptive mother to her office and repeated the book offer on Daoud’s behalf. Her mother refused and informed Arbane. Arbane says her adoptive parents had cautioned her to be careful, but they both passed away in quick succession in 2022 and 2023. When Arbane later brought up the book in a therapy session, Dahdouh assured her, “I’m here to protect you.”

Their sessions continued until Dahdouh and her husband moved to France in 2023. They stayed in touch afterwards. Although the situation felt uncomfortable, Arbane had made it clear she did not want her life used in Daoud’s writing. She also trusted that her most personal details were safeguarded by patient-doctor confidentiality.

Daoud’s novel Houris was published in France in August 2024. Soon after, Arbane and her family began receiving calls and texts about the book. In September, a childhood friend messaged her: “I’m with a guy and his wife. They’re talking about Algeria. He mentioned a writer who published a book, and the story sounds like your life. 😱”

Arbane forwarded the message to Dahdouh, adding, “Congratulations on the book.”

Dahdouh replied that she would bring her a copy, noting, “The heroine has a daughter she calls ‘ma houri.’ The story sounds a bit like yours.”

Arbane kept asking Dahdouh for clarification. A few weeks later, she wrote again: “Hi Aïcha, I hope you’re doing well. I got a call today from a woman saying there’s a book by Kamel that talks about [my] story.”

The next day, she received a more formally worded response: “Dear Saâda, I hope you’re well. Kamel’s writing often provokes strong reactions. Some people are saying the same thing about other characters… I’ll bring you the book so you can read it yourself. What seems to annoy [those people] is that the character named ‘Aube,’ who resembles you, is portrayed as a heroine.” Dahdouh added, “I hope the story doesn’t bother you too much.”

“I had more and more questions in my head after each sentence,” Arbane recalled.

Arbane says Dahdouh gave her a copy of the book while visiting Algeria in October 2024. It was inscribed by Daoud: “Our country has often been saved by courageous women. You are one of them. With my admiration, Kamel.” Still, Dahdouh warned her not to read it, suggesting it might be too emotionally heavy.

Arbane didn’t read it immediately and maintained her friendship with Dahdouh. A few days later, Arbane recalls, Dahdouh left her son at her house. When she came to pick him up, they began talking about it again.Dahdouh suggested that Daoud might share Arbane’s story with a filmmaker for a potential adaptation. She said Arbane could benefit financially from a film, which would allow her to buy an apartment in Spain, where her husband had family.

“This confirmed my fears,” Arbane told me. Finally, she began to read the book. She says she didn’t sleep for the next three nights. “I felt betrayed, naked,” she said. “The entire world was reading something that was mine.” Arbane’s relatives told me her mental health declined after the book was published. Daoud had “slit her throat a second time,” a relative said.

After reading the book, Arbane contacted a cousin of her adoptive father who was a lawyer. Following her advice, Arbane went to the hospital in Oran where she had seen Dahdouh and requested her medical file. The hospital refused to hand it over. According to her French lawyers, she lodged a complaint on November 18. She says the judge asked for the file, but the hospital claimed they could not find it.

Arbane’s lawyers have identified approximately 30 similarities between Arbane and the character “Aube” in the novel. Both are rare survivors of a terrorist attack in which their throats were slit. Both lost the ability to speak and could only whisper afterward. Both received tracheostomies. Arbane’s biological parents were shepherds; Aube’s parents raised sheep. Like Arbane, Aube describes being compared to Donald Duck and recalls a period when she could only eat liquid food.

Similar to Arbane, Aube lives in Oran; one of the apartments she lived in—including the neighborhood, building letter, and floor—is mentioned in passing in the book. Arbane was adopted by a former minister of health, who was also an adoptee; Aube was adopted by a famous lawyer, who was also an adoptee. Arbane’s adoptive mother never celebrated Eid, the Muslim festival where sheep are traditionally slaughtered. The same is true for Aube’s adoptive mother. Both Arbane and Aube attended a high school called the Lycée Colonel Lotfi, owned a hair salon, and love perfume and horses.

Arbane’s aunt, Fadhela Chenntouf, told me that although she and her niece were very close, reading the novel revealed things about Arbane she never knew. In the book, Aube’s tattoos commemorate her murdered family. Arbane also has several tattoos, including one that honors her biological mother. “She never said the tattoo had a meaning for her, but she told Aïcha Dahdouh,” said Chenntouf.

Arbane’s lawyers claim she confided in her therapist about the difficulties she faced upon discovering she was pregnant, just as Aube does in the novel. Like Aube, Arbane obtained three pills for a possible abortion, though abortion is illegal in Algeria. Like Aube, she did not take the pills and gave birth to a child. Even the scar across their necks is the same length: 17 centimeters.

Daoud’s response to the Arbane case evolved in the months after his novel’s publication. Initially, in a September 3 interview with the French magazine Le Nouvel Obs, he said he was inspired by a “woman with a breathing tube, though she was not the only mutilated one.” This was several weeks before Arbane appeared on Algerian TV, accusing Daoud of using her life story for the novel. The following week, on November 21, 2024, Arbane’s Algerian lawyer, Fatima Benbraham, held a dramatic press conference, announcing that Arbane was suing Daoud and displaying pictures of her scars. “He built his success on Saâda’s misery. For a second time, he strangled my client’s voice,” she said. “He stole her life, her story, and her pain, and he leaves her without any life at all.” The lawyer later appeared on a TV talk show to launch a highly personal attack on Daoud, his new life in France, and his family. (Benbraham did not reply to a request for comment. Arbane changed lawyers in JIn July 2025, Benbraham also filed a separate lawsuit against Daoud and Dahdouh on behalf of an association for victims of terrorism. He argued that the book violated the 2005 reconciliation law, which limits public discussion of the “black decade.” This law had only been invoked three times previously, each time in response to political statements and never against a novelist.

Following these events, Daoud’s public comments about Arbane shifted. On December 3, 2024, nearly two weeks after Benbraham’s press conference in Algiers, Daoud published an article in Le Point describing Arbane as a puppet of the Algerian government. “This victim of the civil war is being manipulated to achieve a goal: to kill a writer, defame his family, and preserve the deal between this regime and these killers,” he wrote. He added, “Apart from the visible injury, there is no common ground between this woman’s unbearable tragedy and the character Aube.” In the same article, he claimed Arbane’s story was already known in Oran, citing a Dutch newspaper article published two years before his book—though that article contained only the barest outline of her experience. He did not acknowledge knowing Arbane personally or that his wife had been her psychiatrist.

In February 2025, new evidence surfaced that appeared to support Arbane’s claims. The French investigative outlet Mediapart reported that the novel’s working title had been “Joie” (Joy), a translation of the name Saâda. According to Mediapart, an earlier draft of the text included the dedication: “To an extraordinary woman, the real heroine of this story.” (Daoud did not respond to Mediapart’s inquiries. Gallimard also did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Last summer, I contacted Daoud by email. He replied almost immediately, thanking me for my interest. Over the following months, we exchanged a few brief emails. He declined to meet in person. He wrote that the case against him could not be fully understood without examining “the abuses, mass arrests, the regime of terror, the suppression of the press, and multiple imprisonments in Algeria.”

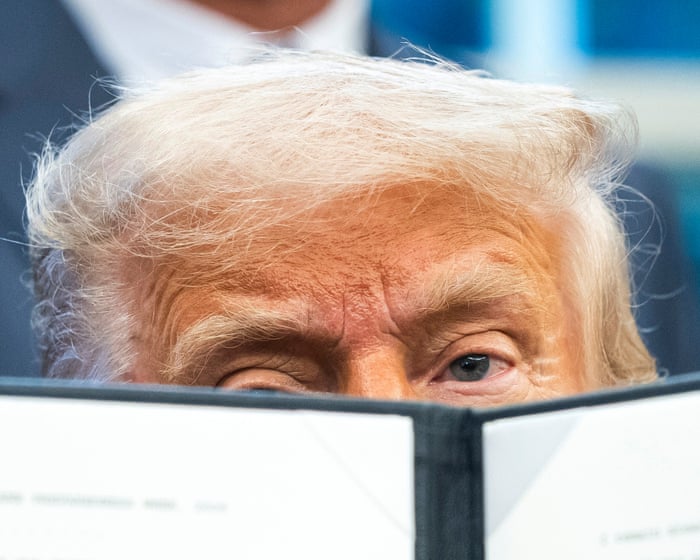

Kamel Daoud in Strasbourg, France, in April 2025. Photograph: Abaca Press/Alamy

In recent years, Algeria has grown increasingly repressive. In 2019, a popular uprising known as the Hirak movement protested against President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s potential fifth term. It was a broad-based movement: “Men and women, all classes, all political backgrounds as well,” according to Mouloud Boumghar, a law professor who has worked extensively on human rights in Algeria. However, it was crushed with the onset of COVID-19 lockdowns.

Bouteflika resigned in 2019 and died in 2021. Since 2019, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, who had served in various roles in Bouteflika’s cabinet, has been president. Today, Boumghar says, no one can stand out, and no voice can speak up without risking prison. “The regime once clamped down more intelligently,” he notes. Now, “it’s brutal.” Since President Tebboune came to power, Daoud wrote to me, almost “no press conference, no debate, no media or partisan campaign has been allowed outside official communications.” Dozens, even hundreds, of people have been arrested—”influencers, activists, publishers, singers, military personnel, opponents.” In France, the persecution of French-Algerian novelist Boualem Sansal has drawn particular attention. In 2025, Sansal, a critic of the Algerian regime, was sentenced to five years in prison for “attacking national unity.” President Macron stated that Algeria was “dishonouring itself” by imprisoning the writer.

Daoud was not always such an outspoken critic of the Algerian government. For much of his career, according to his former editor Hadjadj, Daoud “wasn’t an ally of power, but he wasn’t an opponent.” He pointed out that President Tebboune had once chosen to grant a rare interview to Daoud.In 2021, Daoud became a colleague at Le Point. However, in the following years, as the government grew more repressive, he intensified his writings against the regime, which in turn seemed to target him. In Le Point, Daoud described how, after he hosted Macron in Oran in 2022, guests at their dinner faced “legal harassment” and the restaurant owner was forced to close for a period. “I myself faced online harassment, troll farms, and surveillance,” he wrote. As relations between France and Algeria worsened, he felt that “the machine was about to close in on me. I am a writer, French-speaking, Arabic-speaking, independent and unique. I was called a ‘traitor.'”

In August 2023, Daoud received a phone call from the head of the secret service in Oran, who invited him for coffee at his office. Daoud later wrote that such an invitation “is always the prelude to an arrest in Algeria.” Shortly after, he and his family left Algeria for Paris. “When we arrived in Paris at 6 a.m. in the summer, I immediately started writing Houris, as though it were a sacred dictation,” he said.

Since Arbane launched her legal action, Algeria has issued two international arrest warrants for Daoud; in June, he canceled a trip to Italy for fear of extradition. Daoud told me that, unable to return to Algeria, he recently missed his mother’s funeral. He pointed to the Algerian state’s aggressive response as an explanation for the current affair. In an email, Daoud noted that many individuals propagating and backing the case against him had ties to the regime, suggesting this was further evidence of a state-led campaign. (Arbane’s lawyers in France have filed another suit for libel against Daoud and Le Figaro, after he dismissed the idea that Arbane had a case of her own and suggested she was a tool of the Algerian state. Arbane says she does not follow politics.)

In his emails, Daoud did not address Arbane’s specific accusations but stated that “the character Aube is imagined, a pure fiction.” In December, I sent him a detailed list of questions about specific claims in this article. In response, I received an email from his lawyer, Jacqueline Laffont-Haïk, who said she and her colleagues had provided long, detailed legal submissions to the court, along with evidence showing that “Madame Arbane’s story goes against reality.” She did not offer anything specific. When I wrote again in February to ask if she would share this evidence, she did not reply.

Within Algeria’s literary community, the Arbane-Daoud legal battle has been viewed with ambivalence. Daoud is a polarizing figure in his home country, and as he has gained readers in France, he has lost admirers in Algeria. Faris Lounis, an Algerian literary critic who has written extensively about Daoud, believes he is successful because he tells French conservatives what they want to hear. “The Algerian writer has to be useful,” he told me. (Lounis cited a column where Daoud accused French Muslims of being “useful idiots” for the French left.) In his columns for Le Point, Daoud often criticizes Algeria—a fact interpreted differently, several people told me, coming from a writer now living in France. Another Algerian reader described Daoud’s columns this way: “It’s Arabs, Muslims, Arabs, Muslims, morning, noon, and night—that’s only a slight caricature.”

Although Houris was well received in France, its reception among Algerian readers and scholars has been more complicated. Tristan Leperlier, a scholar of novels from the black decade, described Houris as a “heavily political novel, bogged down in clichéd images, caricaturing oppressed yet heroic women and violent imams.” Leperlier and others point out that numerous books and fMany films about the Algerian civil war have been made, often by women—a point Daoud has largely overlooked in interviews. Yet no one denies that the Algerian state has made life extremely difficult for him. As Lounis notes, “There’s Daoud’s use of Saïda Arbane’s story… That’s one fact. And then there’s the state’s instrumentalization of the case.” Hadjadj calls the media campaign against Daoud a “lynching,” adding, “He’s living through something absolutely terrible.” But he also points out that this has ended up “overshadowing Saïda’s story.”

In France, the Daoud case quickly became entangled with that of writer Boualem Sansal, according to literary critic Elisabeth Philippe. “Very quickly, we made it into a political issue,” she said. From there, it was swept into the fraught public debate over Franco-Algerian relations, which in France often circles back to Islam and immigration. For instance, during a TV discussion about Sansal in June, writer Pascal Bruckner called Algerians a “brainless people,” adding, “They kicked us out, and now they want to come here.”

Amid the uproar, Daoud’s novel The Meursault Investigation has sold over 450,000 copies, and English rights have been secured. When Daoud appeared on France Inter radio in July, the conversation focused more on Sansal’s imprisonment than on the substance of Arbane’s allegations. The host asked Daoud, “Between these legal trials, Boualem Sansal’s fate in prison, the pain of exile, but also the recognition you’ve achieved as a popular writer, how did you live through and cross this year full of headwinds?” (Sansal was released in November 2025.)

The legal case in France is ongoing. Arbane’s lawyers there are focusing on privacy infringement, citing a precedent from 13 years ago when a French author was ordered to pay €40,000 for using details about her husband’s former partner in a novel. In Algeria, Arbane’s case appears stalled; her lawyer did not respond to requests for comment. One journalist speculated that Algerian authorities may be waiting for the outcome in France.

Daoud has built his career on his unique position: an Algerian from a small town who rewrote a Nobel laureate’s work, speaking to both Algerian and French audiences. In a recent book titled Sometimes, One Must Betray, he writes of his pride in being “unfaithful to rigidity… a proponent of plurality, multiplicity, variance and wandering.” Yet challenging an authoritarian regime requires a stubborn self-belief that can itself become rigid. In our exchanges, Daoud framed his struggle as one against a larger Algerian system, stating, “I attempted to illustrate the long healing process that ‘Aube’ courageously undertook, but which Algeria itself rejects; instead, the writer is criminalized for his work, while those responsible for Algeria’s bloody decade enjoy pensions and total impunity.”

The Meursault Investigation is a novel about sacrifice. Its protagonist, Aube, describes herself as an unwitting sacrifice to both the civil war’s terrorists and the modern state, comparing her injury to that of animals slaughtered during Eid. Through her, Daoud seems to ask what sacrifices victims of the war have been forced to make for Algeria to move forward, and what modern Algerians have been compelled to conceal or forget.Should they forget, or suppress their memories for the sake of their country? In our conversations, he implied that he had also made sacrifices. To write about the civil war, he explained, was to put himself in danger. “That period is taboo; anyone who speaks of it risks going to jail.”

To tell someone’s story, as Arbane contends, requires a different kind of sacrifice. Repeatedly, while reading Daoud’s many legal responses, I noticed how Arbane—her claims, her very person—was absent from his view of his own work. For every specific point raised about her, Daoud’s reply would shift to the crisis in Algeria, or the forgotten civil war, deflecting questions about one living woman with references to 200,000 dead.

Toward the end of Houris, Aube returns to Had Chekala, “to the heart of her own story.” Until then tightly woven, the novel’s plot seems to come undone. The pace quickens; the characters take on an allegorical sheen. The village is filled with mysterious donkey heads. An imam in a mosque is also a butcher. It is suggested that he and his twin brother took part in wartime violence. Aube is attacked and tied up in a shed. But just before her throat is cut one final time, she is unexpectedly saved by Aïssa.

Throughout all this, Aube tries to speak but cannot make a sound. Her voice “rustles like crumpled leaves” and “scatters in handfuls of sand.” She begins to cry. Why did she come all this way only to end up locked away? Why is she the only survivor searching for the truth about the war? She thinks to herself, “I was an offering wondering what the point of its sacrifice had been.”

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQs I felt exposed and betrayed A Novelist a Life Story

Beginner Definition Questions

What is this story about

This refers to a situation where an acclaimed novelist is accused of using someone elses personal life storywithout their consent or creditas the basis for a novel leaving the reallife person feeling exploited and violated

What does taking a life story without permission mean

It means a writer uses specific identifiable details events or the core narrative of a real persons life in their fiction without asking that person often changing names but leaving the essence recognizable

Is this illegal Isnt all fiction inspired by real life

Its a complex area General inspiration is legal but it may cross into illegality if it defames someone violates a confidentiality agreement or uses highly private copyrighted personal material The primary issue is often ethical not strictly legal

Whats the difference between inspiration and theft in writing

Inspiration uses reallife emotions themes or broad ideas as a springboard for a wholly new fictionalized creation Theft copies the unique specific sequence of events and personal details that belong to a particular individuals story

Ethical Personal Impact Questions

Why would someone feel exposed and betrayed by this

Seeing your private pain joy or trauma repackaged as public entertainment without your control can feel like a profound violation of trust and privacy It can make you feel like your life is not your own

What are the common arguments for the novelist

Supporters might argue that writers have always drawn from life that transformation into art justifies the use that the story is now a work of fiction or that the real person might be misremembering or exaggerating their own importance to the narrative

What are the common arguments for the person whose story was taken

They argue that their autonomy and dignity were disregarded that they should have the right to control the narrative of their own life especially if it involves trauma and that the novelist profited from their suffering without acknowledgment or compensation

Can this happen between friends or family

Yes its very common in these closer relationships A writer might believe they have implicit permission or that changing details is enough while the friendfamily member feels